High Island Offshore System brought several ‘firsts’ to pipelining in the Gulf of Mexico

Largest-diameter pipeline laid by ‘world’s largest pipelay barge’

Bruce Beaubouef

Managing Editor

Editor’s note: This article is part of an ongoing series on notable achievements and milestones in Gulf of Mexico pipelay history.

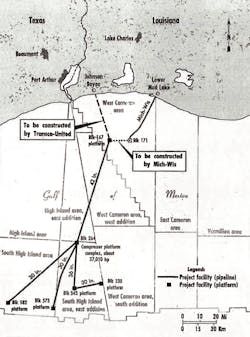

The High Island Offshore System was the first subsea pipeline to tap newly discovered gas reserves in the outer continental shelf in Texas waters. (FromOil and Gas Journal, Jan. 3, 1977, p. 48)

The decade of the 1970s was a boom time for offshore pipeline installation activity in the Gulf of Mexico. Much of this activity was driven by gas transmission companies, who were looking for new sources of natural gas to serve growing onshore markets. In the first half of the decade, the most notable example of this activity was the construction of the Stingray pipeline system, which called for the installation of nearly 256 miles of pipe to gather gas from the West Cameron area (for more on Stingray, see the October 2017 issue ofOffshore, pp. 56-57).

But the Stingray system could not satisfy that growing demand all by itself, and other operators and gas transmission companies began making plans for a new major pipeline system in the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1975, a group of four major gas pipeline companies made plans to build a 203-mile, large diameter pipeline network to bring gas reserves discovered in the High Island area offshore Texas into onshore markets.

In September, affiliates of American Natural Gas Co., United Gas Pipe Line Co., Texas Gas Transmission Co., Natural Gas Pipeline Co. of America, and Transco announced plans to build one of the largest natural gas pipeline systems in the Gulf of Mexico.

The same demand for natural gas that had driven the Stingray project also provided the incentive for the High Island Offshore System (HIOS) project. Together, the five partner companies and their affiliates had advanced $300 million to producers to stimulate exploration in the far reaches of the High Island area in the 1973-74 lease sales.

HIOS would be the first subsea pipeline to tap newly discovered gas reserves in the outer continental shelf in Texas waters. HIOS called for 67 miles of 42-in., 26 miles of 36-in., and 110.5 miles of 30-in. pipe. The main trunk of the HIOS pipeline would be the 67-mile, 42-in. trunkline, and the 42-in. pipe would be the largest diameter pipe laid in the Gulf of Mexico to date. The project, estimated to cost $353 million, was scheduled to initially deliver 988 million cubic feet per day from 28 offshore blocks to onshore markets by November 1977. Through expansion and additional compressor facilities, the HIOS system ultimately could handle 2 bcf/d.

It would do so through a branching network of three 30-in. pipelines that would pick up gas from a number of production platforms and deliver it to a compressor platform in block A-264, about 80 miles offshore Texas. The compressor would push the gas shoreward through the 67-mile trunkline to a platform in West Cameron block 167 offshore Louisiana, where the gas would then complete its journey to land via two new pipelines that would transport it to separate points on the Louisiana coast.

One of these to-shore lines was the U-T Offshore System (also known as the UTOS pipeline), a 30-mile, 42-in. system that ran in a westerly direction to reach Transco, United Gas, and Natural Gas Pipeline Co. facilities on the Louisiana coast. Another 12-mile, 30-in. pipeline moved gas to West Cameron block 171, where it connected with an existing Michigan Wisconsin gathering system which brought the gas to shore.

Construction of the HIOS 42-in. trunkline was the first job for Brown & Root’s new third-generation lay barge, theBAR-347, described as “the world’s largest pipelay barge.” (From Brown & Root, Inc./Marine, 1978 corporate brochure, p. 40)

The Michigan-Wisconsin Pipeline Co., subsidiary of American Natural Gas Co., would serve as operator of the new system. In addition to transporting gas for the five partners, HIOS would also carry gas for other producers that had interests in the area.

Lateral pipelines would enable HIOS to connect to 35 existing and planned platforms; and to facilitate future connections, double side-taps would be placed at intervals along the main trunkline from the compressor complex to a near-shore terminal.

As with the Stingray system, Brown & Root and J. Ray McDermott won the bulk of the engineering and construction contracts for the HIOS project. Brown & Root was selected to build and install the 67-mile trunkline, and McDermott was chosen to build 136 miles of 36-in. and 30-in. outlying feeder lines.

HIOS also called for the construction of six pipeline compressor stations, including the largest offshore compressor complex in the Gulf built to date. McDermott was selected to build this main compressor complex in High Island block 264, as well as two others in blocks 343 and 330 in the eastern sector of the gas gathering system.

Brown & Root built the near-shore station and two deepwater stations in the western sector of the system. The manifold station at block 573 was installed in 340 ft of water, the deepest ever for a manifold station in the Gulf to that point.

The 42-in. pipeline from the compressor complex offshore would operate at a high compression level of 1,440 psi, which was another first in the Gulf. The block 264 station had three gas turbine compressors which together had the capacity to move 1 bcf/d.

Construction began on Aug. 1, 1976, one day after the FPC granted permission to build the line. By the time that the construction season had ended in mid-December of that year, some 77 miles of the 203-mile system had been built, and four out of eight platform jackets for compressor and manifold stations had been installed. Brown & Root had installed 51 miles of the 42-in. line, and McDermott had installed 26 miles of 36-in. line and 15 miles of 30-in. line.

The second season of construction on HIOS began in early April 1977. Remaining work included Brown & Root’s installation of the northern 16 miles of the 67-mile trunkline.

Construction of the 42-in. line was the first job for Brown & Root’s new third-generation lay barge, theBAR 347, which the company described as “the world’s largest pipelay barge.” The vessel had been originally targeted to the North Sea market and designed to endure its harsh working conditions.

TheBAR 347was capable of laying double-jointed, large-diameter pipe in extreme water depths without the need of a pipelaying pontoon or extended stinger. The vessel measured 650 ft in length by 140 ft in width, with a depth of 50 ft. It was equipped with a centerline elevated ramp with three pipe tensioners that could lay 36-in. pipe in water up to 1,100 ft deep – a seemingly unimaginable water depth at that time. The barge was equipped with 12 mooring anchors weighing 60,000 lbs each. Each mooring winch had the capacity for 10,000 ft of 3-in. diameter wire. This mammoth vessel dwarfed every other vessel in Brown & Root’s fleet. Thus the “world’s largest pipelaying barge” was launched amid much fanfare at Rotterdam in early 1976.

The christening of theBAR-347 came amidst a heightened focus on new pipelay vessel designs. Buoyed by the growth of the pipelay market in the North Sea and the Gulf of Mexico, several consortia emerged to build new pipelay barges, based on new designs. The semisubmersible design was gaining popularity for the North Sea market, based on the idea that the semi design would be more robust for the North Sea, and able to withstand its harsh environment. One of these consortia included Shell, Esso, and Zapata, and it led to the construction of the Semac-1, which installed the FLAGGS pipeline in the North Sea in 1975. The Semac-1 was the second major semi, although a bit more modestly sized than the Viking Piper, which had been launched by IHC Gusto in 1975. Another consortium was formed by Brown & Root, Oceanics, and Sedco. But after ordering hull steel and major equipment, the consortium dissolved. Brown & Root decided to go it alone and built the BAR-347.

For theBAR 347, Brown & Root had elected to stay with its proven lay barge design, seeking instead to improve the vessel by expanding its design and making it more robust. With accommodations for a crew of 350 and storage for up to 20,000 tons of pipe, the “superbarge” was proclaimed by Brown & Root to be the prototype of the coming third generation of laybarges. But by May 1976, only months after its much-heralded launch, the vessel had already departed the North Sea to work in the tamer waters of the Gulf of Mexico for the HIOS project.

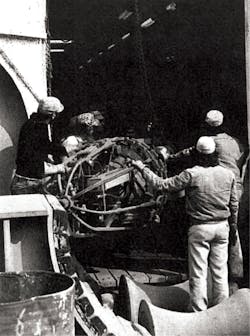

Workers aboard theBAR-347 prepare to store the automatic welding clamp. (Offshore, February 1977, p. 43)

In the field, theBAR 347 was able to take advantage of the latest offshore pipeline installation technologies. During pipe-laying operations, pipe on the conveyor was automatically transferred to a vertical conveyor on the port side forward. The vertical conveyor automatically transferred the pipe to the beveling conveyor. After it had been beveled for automatic welding, the pipe was transferred toward the ramp. From the beveling conveyor, pipe was transferred to a forward, longitudinal conveyor. Pipe was then moved to a short transverse conveyor which automatically transferred to the stalking shoes.

But the “superbarge” was not without its problems. As recounted inOffshore Pioneers, a history of Brown & Root’s marine division, pipeline superintendent “Buddy” Hoke recalled that “Nobody wanted [the] 347.” While “it seemed like those old barges had made Brown & Root fortunes and we had taken them all over the world and they had done real good, and if a little bit was good, a whole lot would be real good. [But] when you ran that 347, you never got sixth sense of where you were at. It was kind of like an arm that didn’t have any feeling in it. The communication was horrible on it. It had another bad flaw that nobody ever wanted to talk about and that was the touchdown point down there, that would buckle the line. At the touchdown, where the pipe touches the bottom.” Nor were these the only problems. According to Willem J. Timmermans, INTEC Engineering President, the vessel almost sank while in transit to the Gulf of Mexico. Once on location, he noted that the vessel “installed a few pipelines with some difficulty.”

J. Ray McDermott’sLay Barge 23 completed about one-third of its 136 miles during the 1976 season, then installed the rest in the spring and summer of 1977. In fact, to ensure timely completion of its part of the project, McDermott deployed its entire Gulf of Mexico complement of equipment, including its Lay Barges 23and26, on the HIOS project in 1977.

Both the Brown & Root and the McDermott vessels laid single joint pipes during the 1976 construction season. TheBAR 347 was capable of laying double joint piping, but the urgency of the project did not allow sufficient time for welding double joints onshore. The BAR 347 used a combination of the CRC automatic welding process and manual rod welding while the two McDermott barges used the manual rod method only.

Construction of the 42-in. trunkline required continuous inspection by diver crews before and after the line was laid. The maximum depth of the 42-in. line was 150 ft at its terminus in block 264. A combination of submarine vessels and divers were employed to inspect the laying of the 36-in. and 30-in. lines, since these were laid in deeper waters.

The McDermott laybarges employed buckle arrestors at intervals of 500 ft on the 30-in. line at depths greater than 150 ft of water. The buckle arrestors were used on all 30-in. pipe south of the block 264 compressor station, but they were not necessary for portions of the 36-in. pipe at similar depths.

For corrosion protection, bracelet-type exterior cathodic protection was installed along each of the HIOS pipelines at intervals of 1,000 ft. An inhibitor was added to the gas stream for internal corrosion protection. The 42-in. pipe had an asphalt covering and the 36-in. and 30-in. lines were coated with Somastic, an asbestos type of coating which was widely used well into the 1960s, when environmental regulations made its use prohibitive. Some of the 36-in. pipe and all of the 42-in. pipe was spiral welded.

The HIOS pipeline was completed on schedule and placed in service in early 1978. It would go on to gather and move natural gas from the Gulf of Mexico to coastal and onshore markets for years. And it would be connected to the Stingray pipeline through the HIOS East Extension, a relatively short 30-in. pipeline that ran from east to west through the East Addition of the High Island Area South Extension area, from High Island block A343 to A330. With this connection, both HIOS and the Stingray pipelines became part of the larger natural gas gathering and transmission network that was being built in the Gulf of Mexico in the 1970s.

Like the Stingray pipeline, HIOS would continue to serve as an important pipeline artery for moving natural gas from the Gulf of Mexico well into the 21st century.

HIOS featured a number of firsts for Gulf of Mexico pipeline installation, including installation of the largest pipe diameter to that point; the largest offshore compressor complex in the Gulf; the highest level of compression employed upon a Gulf of Mexico pipeline; and the “world’s largest pipelay barge” – although that barge evidently had its problems. After completing its portion of the HIOS project, theBAR-347 was then transported to Southeast Asia.

In terms of water depths, HIOS reached its maximum depth at 340 ft in block 573 of the High Island South Addition Area. That was short of Stingray’s maximum water depth, which reached 365 ft in block 639 of the South Addition of the West Cameron Area. Both were soon eclipsed by another project which nearly tripled the maximum depths reached by HIOS and Stingray. As operators and E&P firms continued to look for ways to bring natural gas to onshore markets, Shell’s Cognac project in the late 1970s would surpass anything built in the Gulf of Mexico to that point.