Gathering system addressed shortages in key markets

Bruce Beaubouef

Managing Editor

Entering the 1970s, the oil and gas industry in the Gulf of Mexico had evolved into a mature enterprise with sophisticated drilling and production technologies. Gulf operators were producing abundant amounts of crude oil and natural gas that helped fuel America’s economy.

By the mid-1970s, offshore Louisiana accounted for about 17% of the natural gas and 18% of the oil produced in the United States. Pipelines became the key to moving offshore production to onshore markets.

But despite this abundant production in the Gulf, by 1970 there were severe energy shortages afflicting major urban areas in the nation. In particular, shortages of natural gas became the primary energy supply concern in several markets in the US Midwest, Northeast, and East Coast.

The gas shortages were largely driven by short-sighted federal regulations that led to imbalances between interstate and intrastate markets. Federal price control of natural gas in interstate markets followed in the wake of the US Supreme Court’s decision in the case ofPhillips Petroleum Co. vs. Wisconsin in 1954. This decision led the Federal Power Commission to promulgate a complex and unwieldy set of price controls on natural gas sold interstate markets. Slowly but surely, producers in resource-rich states began to focus on supplying gas to the unregulated intrastate market, at the expense of the interstate market. The result was gas shortages in several important Midwest and Northeast markets. These shortages in turn led to supply curtailments on a number of key gas transmission systems that served those markets.

It was this set of market conditions that led a number of gas transmission companies to invest in offshore exploration and production, and in plans to build new offshore pipeline systems that would bring new natural gas supplies to underserved markets. The transmission companies took heed of the growing opportunities for resource development in the Gulf of Mexico.

The Stingray pipeline project was the response of two major gas transmission companies – Trunkline Gas Co. and Natural Gas Pipeline Co. of America (NGPL) – to redress looming shortages. In the early 1970s, Trunkline, a transmission company within the Panhandle Eastern system, and NGPL, a subsidiary of Peoples Gas, formed a joint venture to study ways of adding gas from the Gulf into their pipeline systems.

Wayne Simpson, executive vice president of NGPL, noted that deliveries from a new offshore system to Chicago-area customers would help offset declines from onshore sources, and would “help forestall any further cutbacks in our pipeline deliveries to them.” He observed that the company had an unmet demand equivalent to the annual heating needs of 225,000 homes, equal to a city of the size of Boston. The company’s largest customer at that time was Northern Illinois Gas Co., followed by its sister company, Peoples Gas, Light & Coke Co., and then Northern Indiana Public Service Co. NGPL delivered 65% of the natural gas used in Illinois and 75% of the gas consumed in the Chicago metropolitan area. Shortages of natural gas were particularly a concern for local distribution companies that were anxious to meet home heating demands for the upcoming winter season.

Like other gas pipeline companies, Peoples Gas had advanced nearly $300 million to producers for the exploration and development of resources in the Gulf of Mexico to help answer growing market demand. Simpson noted that gas had been found on 31 of 88 offshore tracts in which Natural Gas Pipeline had purchased rights, and drilling was still yet to commence on many of them.

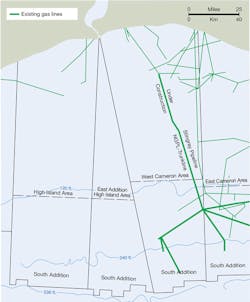

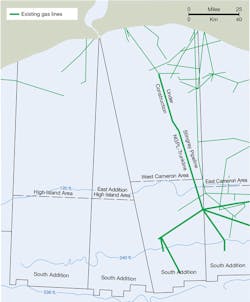

The venture wanted to access the estimated 3 tcf of gas located beneath 17 blocks of offshore acreage in the Vermillion and the East and West Cameron areas located offshore Louisiana. Of the total, 1.1 trillion would be dedicated to the Trunkline system, and 1.3 trillion to NGPL. Through the Trunkline and NGPL systems, the gas would be shipped for delivery to utilities serving markets in Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan. Later, the United Gas Pipeline Company agreed to buy the remainder and transport it through the Stingray pipeline system, on a fee basis. Through United, gas from the Stingray system would reach five transmission companies which served East Coast markets.

Preliminary discussions between Trunkline and NGPL about Stingray began in 1971, just as exploratory drilling in the western Gulf of Mexico was getting underway. At that time, no hard data was available on the availability of offshore resources in this area. But in April 1972, the two companies signed an agreement for the ownership, construction and operation of the Stingray offshore pipeline system.

Plans called for the Stingray pipeline to run with 255.7 miles of 12 ¾-in. to 36-in. pipe to gather gas from the West Cameron area. At a cost of $154.7 million, the Stingray pipeline system would be one of the largest marine pipeline systems ever built in US waters at the time. Importantly, it would deliver 650 MMcf/d of gas to end-users before the 1974-1975 heating season arrived.

The pipeline would originate in West Cameron block 148, starting from an existing NGPL system. From there, the mainline would run with roughly 72 miles of 36-in. pipe to reach block 509 in the South Addition of the West Cameron area. There, it would serve 17 blocks with four separate gathering lines, with diameters ranging from 12¾ in. to 36 in. The gas produced from those fields would enter the respective gathering lines to reach the 36-in. Stingray mainline, which would then connect to the existing NGPL system and then to onshore markets. Trunkline designed the pipeline, and would operate it upon completion.

The Stingray design had several notable aspects. The 22.7-mile, 18-in. gathering line that would connect to block 639 of the South Addition of the West Cameron Area would be laid in waters as deep as 365 ft, the greatest depth at which a major line had been laid in the Gulf to that point. Not coincidentally, the production platform – the Marlin No. 5 platform in block 639 – was located about 125 miles from the Louisiana shoreline, which was the most distant facility in the Gulf to be served by a pipeline at that time.

And the overall Stingray system would have a design capacity of slightly in excess of 1 billion cubic feet per day, matching the largest offshore Louisiana gas lines then in existence.

In 1973, the two Stingray partners brought Pennzoil, owner of United Gas Pipeline Company, into the operation, and together the three firms contributed significantly toward alleviating the shortage in the Great Lakes region. Several distribution companies benefitted from the Stingray pipeline system, including Panhandle customers Consumers Power Company and Battle Creek Gas of Michigan, Citizens Gas in Indianapolis, and Central Illinois Light Company; as well as NGPL’s Chicago-area customers.

Pipelay began in the summer of 1974, and the system was completed in just a few months. Brown & Root and J. Ray McDermott, which had come to dominate the Gulf of Mexico pipelay market, fabricated and installed the pipeline system. Approximately 130 miles of the Stingray system was installed by Brown & Root, including the main artery of the system, the 72-mile, 36-in. mainline. Aided by mild weather and smooth waters, this portion of the line was finished in a record 60 days, ahead of schedule.

Brown & Root and J. Ray McDermott also designed and built “Stingray City,” the offshore compressor station platform complex that kept the gas flowing through the pipeline system. Located in block 509, this offshore “city” included a compressor station, a liquids separation platform, and a three-deck pipeline platform. Extending 100 miles from its offshore base and standing in 200 ft of water, it was further offshore than any other compressor facility at that time. Like the pipeline, “Stingray City” was built by Brown & Root and J. Ray McDermott in the summer of 1974.

Stingray Pipeline Co. officials claimed that their pipeline was “the largest offshore pipeline system to be built in a single year.” The developers were so proud of their project that they invited members of the media on a press tour that enabled them to see offshore pipelaying operations firsthand.

Aboard the McDermott laybarge 22, Kenneth Ross of theChicago Tribune noted that the 150 crewmen aboard worked 12-hour shifts, seven days a week, with every third week ashore. He also noted that the 420-ft laybarge 22 was just one of five vessels employed to build the Stingray system. Aboard the laybarge, Ross was able to see the intricate nature of the offshore pipeline installation process. He noted in his report that “sections of pipe are barged to the laybarge, where they are welded by six welding stations. Each weld is x-rayed to make sure it is proper, because repairing a break once the line is laid can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. There are 30,000 welds in the system. The pipe is then covered with a three-inch layer of concrete to help insure that the line will stay at the bottom.”

Ross further noted that in depths up to 200 ft, the line was buried “in the clay bottom of the Gulf” by cutting a trench with water jets. Beyond 200 ft, only the valves were buried so that they would not “snag shrimp nets.” With that work completed, divers would inspect the line on the bottom up to 200 ft; and in depths greater than that, the inspection work would be performed “by a television camera in a small submarine.” That summer, Ross noted, the weather “had not been much of a problem except on a few occasions.” In the Gulf of Mexico, the pipelay installation window generally ran from mid- May to mid-October. In good weather conditions, the barges averaged about 8,000 ft of 18-in. pipe a day.

The Stingray system would continue to serve as an important pipeline artery for moving natural gas from the Gulf of Mexico well into the 21st century. Many of the onshore markets it served were far removed from the Gulf Coast region. But as the developers recognized, Stingray would not by itself solve the nation’s natural gas shortages problem. Other Gulf of Mexico pipelines would still be needed.