GoM operators looking for value over volume

Bruce Beaubouef,Managing Editor

Operators inthe Gulf of Mexico (GoM) have had success recently focusing on incremental subsea tiebacks and near-field opportunities, and there remains uncaptured upside. However, successful exploration and development of complex reservoirs continues to be a challenge for operators and puts into question the scale of the GoM’s growth potential in the coming years.

New trends in technology, development, commercial models, and financing—and industry players’ responses to these innovations—will determine whether the GoM will return to its former role as a high-margin, cash-generation contributor for the best operators.

To get an in-depth analysis of these trends Offshore recently spoke with Kassia Yanosek, Partner with McKinsey & Co. As a leader of McKinsey’s strategy work within the Oil & Gas Practice in the Americas, Yanosek advises international and national oil companies, exploration and production independents, and service providers on portfolio strategy, capital project delivery, organization, mergers and acquisitions, and technology innovation.

***

Offshore: We are beginning to see the oil and gas market emerge from the downturn that began in 2014. We’re seeing activity pick up in several regions, but it seems like the Gulf of Mexico is still lagging behind. How do you view the GoM market today?

Yanosek:Well, it depends on what you mean by “lagging behind.” When you think about the North America activity yes, there is a lot more focus on onshore and particularly, in the Permian basin, but that doesn’t translate into the Gulf of Mexico necessarily lagging behind. There has been quite a bit of activity over the past 18 months with new discoveries announced and FIDs picking up, relative to the 2014-2016 time-frame.

Several large projects have been sanctioned recently, including BP’s Mad Dog Phase 2 project and Shell’s Vito project. When I look at the Gulf of Mexico, I see a region that is reshaping the future of deepwater E&P. Moreover, we have seen increased activity from newer players who are exploring and developing smaller fields in the Miocene formation-- a good example is LLOG with 30 producing wells and three new subsea tiebacks this year. Another is Talos Energy, an emerging private equity-backed player who recently merged with Stone Energy [to form Talos Energy, Inc.], and have an ambition to grow their position in the Gulf of Mexico. Further, some of the majors are announcing significant capital commitments to the Gulf of Mexico.

However, I think there’s a question about how different operators think about growth in their deepwater portfolios beyond near-field exploration. There seems to be growing appetite by majors such as Shell and Total for pursuing big finds in the Paleogene and in the Norphlet, a Jurrasic play that has gotten a lot of attention lately. While the extent of growth in the next phase of GoM development is still an open question, I would say that we’re seeing a lot more optimism about the future of the Gulf of Mexico.

Offshore: What have GoM operators been doing to reduce their break-even cost, and where do you see break-even cost today in the deepwater and ultra-deepwater Gulf?

Yanosek: Break-even costs for deepwater projects in the Gulf of Mexico have been falling dramatically since 2014. McKinsey’s deepwater cost model, that benchmarks breakeven costs for future projects, indicates that new project breakevens have fallen over 60% on average over the past five years. Today, we see operators publicly reporting forward-looking break-even costs for new hubs in the $35/bbl range, and sometimes less. Break-even costs are even lower for new subsea tieback projects, which leverage the existing infrastructure.

Offshore: Do you factor a return in your break-even, and is it a full cycle break-even?

Yanosek: Yes, we factor in a 10% return on investment in full cycle break-even cost.

Offshore: A 60% reduction in the break-even cost since 2014 seems pretty dramatic. Can you elaborate on this?

Yanosek: Focusing on the actual number can create confusion, as every project is different. But $90 to $100/bbl was a typical break-even in 2014. So yes, costs have fallen by 60% or more. There are two factors contributing to the lower break-even costs. Number one is supply chain compression – supplier margins have fallen about 50% from 2014. Secondly, operators are now thinking differently about how to design a hub to make it more fit-for-purpose, as opposed to a “Cadillac” design with all the bells and whistles. They are also reducing unnecessary redundancies and adapting the size of their project teams to be more agile.

Alongside this, the industry is undertaking efforts to re-think how to reduce waste in the supply chain. Operators are now partnering with suppliers earlier in the design cycle to jointly develop a cost-effective model for deepwater projects. Additionally, industry-wide collaboration efforts such as the JIP33 Capital Project Complexity initiative, hosted by the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers, is creating standard specifications for equipment and components. The subsea tree specification developed by this initiative is estimated to result in roughly 20 to 25% cost savings per tree, even with the same quality expectations.

Offshore: With the resurgence in oil prices over the past year, what oil price do you think is required to keep the Gulf of Mexico viable as an oil-producing region over the long term?

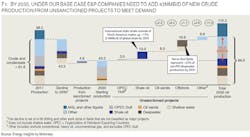

Yanosek: We have run the numbers with our deepwater cost curve model that we maintain. If you assume a $70/bbl long-term price, then by 2030, 90% of Gulf of Mexico projects will be economical. We see that between now and 2030, there will be a significant supply gap that needs to be filled, and onshore production will not be sufficient to make deepwater production irrelevant – especially now when we are seeing deepwater projects that are competitive with onshore projects.

In our lower-case scenario where the oil price is $40/bbl over the long term, then about 45% to 50% of projects in the Gulf of Mexico are projected to be economical. Important to note is that we do not build in any additional technological or productivity improvements into the economics beyond the current state. In view of all of this, we believe that the Gulf of Mexico deepwater has a future in a range of oil price scenarios.

Offshore: Besides oil prices, what other challenges that are unique to the Gulf could unlock E&P activity?

Yanosek: Technology is definitely one of them. Technology has been a big part of the Gulf of Mexico’s deepwater story for two decades, when advances in seismic imaging enabled game-changing discoveries in deeper and more complex areas. Further technology development is required if we’re going to see significant growth in the exploration and development of plays such as the Paleogene. We’ve looked at the recent history of the Gulf of Mexico deepwater and the differences in exploration and development success between the Miocene and the Paleogene. Exploration success rates for the Paleogene have been challenging. The industry has about a 20% success rate on average in the Gulf of Mexico, which is two to three times worse relative to other deepwater regions.

And even when exploration efforts in the Paleogene are successful, most of these finds have not been developed due to resource complexity and uncertain economics. Of the 5 billion barrels of oil equivalent of discovered reserves in the GoM that have been brought online since 2005, 70% of the volume has been in the Miocene play, with only 5% coming from the Paleogene. As a result, operators have in recent years focused on developing “value over volume” because the Miocene plays are smaller find sizes and are typically tying back to existing hubs. We haven’t “cracked the nut” on the Paleogene. There is a lot more room for operators to develop and accelerate the technology that will be needed in this high-pressure, high-temperature environment.

That’s a key question: what will the industry structure of the Gulf of Mexico look like, going forward? It’s not hard to imagine seeing a few majors dominating the basin in the future, who can make these long-term investments and take on the deepwater risk profile. – Kassia Yanosek

Offshore: Over the first half of this year, rig counts have improved in the US Gulf, while not at 2014 levels; we see that the industry has learned to do more from a single rig. Do you think this is still a good metric to assess drilling activity in the region?

Yanosek: It’s a difficult metric to assess these days, because there is a lot more innovation happening on the rig. I do think there’s a bit of a change in approach as to how rigs are used, and how quickly people can get projects online. As mentioned earlier, there are new players in the Gulf of Mexico. Those folks are taking a very different approach – for instance, they may only use one rig even if they are drilling 30 wells. In that type of scenario, it’s a bit hard to use the number of rigs active in the Gulf of Mexico as a proxy for activity.

Offshore: While the oil price outlook is improving, Gulf operators still face other challenges – i.e. regulatory and fiscal and insurance costs remain high. With these higher costs, is it still feasible for the smaller companies to play a meaningful role in the Gulf, or are we getting to a situation where really this is kind of a “big boys club” – the super majors, national oil companies and such. What implications might that have for Gulf E&P going forward, if that’s an accurate assessment?

Yanosek: That’s a key question: what will the industry structure of the Gulf of Mexico look like, going forward? It’s not hard to imagine seeing a few majors dominating the basin in the future, who can make these long-term investments and take on the deepwater risk profile.

Interestingly, while a number of large independents left the basin after the 2014 oil price collapse (Noble Energy, ConocoPhillips, for example), we are now seeing a rise in activity in the basin from small, private-equity backed companies I referenced earlier, who focus on near-field exploration and brownfield developments. One could argue that the future Gulf of Mexico could eventually look more like the North Sea, where you see a number of the incremental type developments done by these players who are more nimble and have better operating efficiencies than some of the majors. That said, there is no denying that we will continue to see investment from the larger majors who are making large capital commitments to the Gulf of Mexico.

Offshore: Do you think we will see more of a brownfield/subsea tieback approach in the Gulf, going forward?

Yanosek: Since subsea tiebacks leverage existing infrastructure, they are an economical field development option that will continue to be favored in the Gulf going forward. There is a question, however, for some of the independents who focus on this strategy: How are they going to continue to grow if subsea tiebacks are their only strategy? If they’re a Gulf of Mexico player and their whole business model is based on subsea tiebacks, you’re going to probably see them grow through acquisitions and partnerships so that they can access more fields and more capital.

Offshore: We’ve seen a lot of consolidation over the past two years, and new partnerships are forming as well. What is your view of some of these business alliances? Do you think they can help the industry move forward with new projects in the Gulf?

Yanosek: Operator partnerships and alliances have and will continue to be a strategy for many companies, particularly as companies look to share risk and capital commitments for emerging plays in the Paleogene. A new trend we are seeing is that majors are beginning to partner with small independents on exploration.

Additionally, we see that the offshore players in the Gulf of Mexico could derive great benefits by pooling equipment and resources in the same way that the North Sea industry operates. Doing that in a way that coordinates the industry could be an opportunity for value creation.

We are also seeing an interest in new approaches to producer/ supplier relationships. For example, operator-supplier partnerships to standardize engineering designs and equipment – in early stages of project development – are being developed to speed cycle times. We are also seeing an emergence of new commercial models between equipment providers and operators that were pioneered in the aerospace sector, that align incentives across operators and equipment suppliers through risk-sharing and jointly sharing in the value of an end-to-end project. These are models in which all participants can share in the upside of improved utilization.

Offshore: Let’s go back to the topic of deepwater break-even costs – does the industry need to bring the break-evens down even further to make deepwater increasingly competitive with onshore, to help get some more projects to FID? And if so, where can the industry find the savings?

Yanosek: If you look at the history of the deepwater Gulf of Mexico, back in the early 2000s operators were sanctioning projects at $25/bbl. So, you might ask: “How do we get back to those days?” Just a few years ago, it was hard to imagine ever repeating that. But I do think that there is opportunity to even further reduce costs and improve productivity, beyond what has been achieved in the last few years.

There is also still quite a lot of waste in the system. We haven’t even maximized all of the potential cost and productivity savings from engineering improvements. And digital technologies have the potential to further transform deepwater economics. Exploration analytics, for example, are being used to identify new resources and have the potential to transform competitiveness in exploration. In the North Sea, operators are using technology to increase recoveries. While still nascent, remote operations enabled by technology and analytics will be part of the GoM’s future operating model across the lifecycle of a field.

We’re at the early stages, but digital has the potential to be a significant game changer for the Gulf of Mexico going forward. •