Shell advances deepwater projects with capital efficiency, re-engineering

The hull of the Appomattox platform departed from South Korea en route to Ingleside, Texas, in August. (All images courtesy Shell, except as noted)

‘Competitive rescoping’ lowers break-evens

Bruce Beaubouef

Managing Editor

Offshore operating companies have been hard pressed to keep their deepwater projects economically viable amidst the lingering downturn.

But Shell evolved its deepwater business so that the company is enabled to continue advancing its Kaikias, Appomattox, and Coulomb Phase 2 projects in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico. This includes structural re-engineering and what Shell calls “competitive rescoping” to lower its break-even costs and reduce cycle times.

Offshore recently spoke with Donal Rajasingam, Asset Manager–Gulf of Mexico West and Rick Tallant, Asset Manager–Gulf of Mexico East to get an insight into this strategy, and get an update on Shell’s upcoming deepwater Gulf of Mexico projects.

“Shell has always been at the forefront of the driving technology, and being able to unlock challenging deepwater reserves,” says Rajasingam. But when the price of oil fell in 2014, “we realized that we were not particularly competitive when it comes to the cost performance of delivering those capital projects. So, the break-even prices that we were typically seeing on new project investments were borderline relative to where oil prices actually were.”

Competitive rescoping

It was in this context that Shell’s design engineers began what the company called “a competitive rescoping” of its upcoming deepwater projects. This effort started with “stripping down” all the basic exploration and production functionalities, and “turning the design process on its head,” Rajasingam said.

“We wanted to know what was needed to keep an operation safe, but to boil down to that level; and at the same time find out what is possible in terms of keeping equipment operational,” Rajasingam explained. “We established baselines which ensure that the project meets our safety requirements and minimum operational functional specifications. There had to be a real ‘value-add’ justification to add to the scope or design elements on top of that. That’s what we call competitive scoping.”

In some cases, design engineers removed or reduced redundant systems, while at the same time improving Shell’s ability to run equipment for longer without failure. “We refocused on the efficiency at which we run the equipment in order to get availabilities and schedule deferment that’s up in the top quartile now,” Rajasingam noted. This, in turn, has enabled Shell to lower its break-even prices, such that its upcoming deepwater projects are often competitive even with onshore Permian operations.

Tallant elaborated on the strategy. “We have spent a lot of time over the past couple of years rescoping our projects and understanding the best and most efficient way of producing these fields,” Tallant said. “We also looked at ways in which we could shorten cycle times to be able to get the returns and the cash flow faster.”

Shell worked with its vendors and contractors to find ways of making its engineering and design concepts more efficient, and to look for new ways of reducing project costs.

A case in point, Tallant notes, is Shell’s upcoming Kaikias project. Located in the Mars-Ursa basin, the Kaikias field is estimated to contain more than 100 MMboe of recoverable resources. Production will tieback to the nearby Ursa TLP, located in Mississippi Canyon block 810, just 6 mi away. The project will be developed in two phases. The first phase includes three wells tied back using a single flowline to the Ursa production hub. The wells are designed to produce up to 40,000 boe/d. Phase one is expected to start production in 2019.

“We’re using an existing facility to tie into, and we’re using the existing process system on the Ursa TLP to further reduce capital costs on Kaikias,” Tallant explained. “In the past, we may have wanted to build a new processing train or make some other modifications. But with this lean approach, we have been able to find a way to use the existing facilities on Ursa, with some minor modifications, that allow us to bring the capital costs down even further.”

By simplifying the design and using lessons learned from other projects, Shell has been able to reduce the total cost on Kaikias by nearly 50%. “We’re making use of assets that have already been capitalized,” says Tallant. “If you look at both Mars and Ursa, production has been ongoing for years, and now there’s available capacity in those systems. There’s significant available weight, space, and capacity at those facilities, because those fields have probably seen peak production. Kaikias is six miles away from the Ursa platform. Using those assets is the most efficient way to produce those barrels. It just makes sense.”

Drilling and completion

Reducing drilling and completion costs was a key focus area, on Kaikias and other projects. In the wake of Macondo, Shell took a fresh look at its drilling programs, both in terms of safety and efficiency. The lean approach has paid dividends with the advent of the market downturn. “When we looked at our well designs, they were often quite complex in the past,” Tallant said. “We’ve rescoped those to make sure that we’ve looked at the drilling margins, and that we have understood the safety concerns. No matter what we do, we’re going to have a safe well. We’re not going to do anything that is going to compromise safety. But, we found that there are well designs that are more efficient, and that we can drill these wells faster.”

The search for drilling efficiencies led Shell to adopt a standardized well design. In the past, Tallant notes, each individual well might have had a bespoke design. “So, we had to have the correct, specific equipment, the backup equipment, and everything else that was aligned with that individual design. Now we’ve gone in and said if we’re going to drill a 14-in. hole, then a 14-in. hole is going to have a certain standard design, with a standardized type of casing. That way, you can use economies of scale, and make orders for multiple wells across the portfolio. You can have backups from each of the individual wells to help each other, rather than buying two sets for every single well.”

The result has been significant operational efficiencies, greater savings, and less downtime. “Honestly, it makes things run much faster,” Tallant observed. “We find that if you standardize the well and all its various components, the crew knows exactly how to drill and complete each well. They’ve done it before with the same type of well they’ve done previously.”

And, Shell has been able to take advantage of lessons learned from decades of operating in the Gulf. “We’re drilling in basins that we know quite well,” Tallant notes. “We know what the reservoir pressures are. We know how those have worked. And we have really challenged ourselves in terms of the casing design.” By standardizing its well design, Shell has been able to reduce the amount of casing needed per well, which brings further savings. This can be done while still maintaining a safe well, Tallant says. “Of course we want to drill a well safely, but we also want to be more efficient, and shorten the duration of drilling.”

Structural re-engineering and “competitive rescoping” are enabling Shell to continue to advance its deepwater program in the current low oil price environment.

Reducing spread rates has been another major factor in lowering drilling costs. Shell employs long-term rig contracts for its drilling campaigns, which means that the rig day rates are pretty much set. “But the spread rates on top of that are what we’ve gone after,” says Tallant. By employing a “demand-based system,” Shell has gone from having about 60 offshore supply vessels down to about 10 or 11 today. “And we’re doing about the same amount of activity as we did back then.”

Overall, Shell has taken a fresh look at the way it schedules and executes logistics offshore. “That was one of our biggest costs,” Tallant said. This approach entails “being smarter with rentals, looking at inventory that we’ve had, and standardizing equipment and designs.” To succeed in the deepwater arena in a down market requires “a little bit of everything,” Tallant notes. “There is no one magic bullet that does everything for you.”

Subsea equipment

Shell has also worked with its vendors to standardize their subsea offerings, and bring those costs down as well. A key part of this was a systematic effort to standardize subsea trees. Shell worked with FMC Technologies Inc. (now TechnipFMC) to move toward standardization of tree design and components, and subsea flowline concepts. “We asked them: ‘What kind of designs do we need? Do we really need dual flowlines, or can we get by with one?’”

For a number of Shell’s upcoming deepwater projects, engineers determined that field development could move forward with only a single flowline. This has led to considerable capex savings. “Having a dual flowline is a nice luxury – it gives you operational synergy and offers flexibility, but it overcapitalizes you upfront,” Tallant said.

Kaikias has been a good example of these structural re-engineering efforts, Tallant says. Shell engineers decided to go with a single flowline, rather than a dual flowline. “In the past, and with higher oil prices, I think we would have gone with a dual flowline system,” Tallant observed. “In this case, we’re going with a single flowline system, which has really reduced costs from the subsea side.”

The Appomattox development initially will produce from the Appomattox and Vicksburg fields, with average peak production estimated at 175,000 boe/d.

Other key subsea components for Kaikias include trees, jumpers, and subsea flowlines. “We are doing lots of standardization there,” Tallant says. These standardization efforts are enabling Shell to take a portfolio approach across the fleet, bringing significant economies of scale. And there are benefits to vendors and suppliers as well. “Standardizing allows our suppliers to reduce costs significantly, and thereby lower the cost that they charge to us. That’s been a significant source of saving on the subsea side.”

By taking a hard look at the three main components of Kaikias – the wells, the subsea system, and the tie-in – Shell has been able to optimize the design through the entire field development, and that in turn “has brought the break-even price down quite a bit,” Tallant says.

“Our drilling costs on Kaikias have come down probably about 50% from what they would have been at the beginning of the down cycle,” Tallant observed, “and subsea costs are down about 30% as well.” He notes that these efforts have brought break-even prices for Kaikias down below $40/bbl, which means that the Kaikias project “can compete with pretty much anything in our portfolio in the United States. The same is true for Appomattox.”

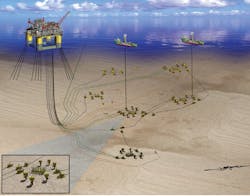

The Appomattox development is located some 80 mi (129 km) offshore Louisiana, in approximately 7,400 ft (2,195 m) of water. It will initially produce from the Appomattox and Vicksburg fields, with average peak production estimated at 175,000 boe/d Shell-share. The project calls for a semisubmersible, four-column production host platform; a subsea system featuring six drill centers; 15 producing wells; and five water injection wells.

The hull of Shell’s Appomattox production platform onboard the M/V Xin Guang Hua. (Courtesy COSCO Shipping Heavy Transport)

“With Appomattox, we were already well under way with project design before the market downturn,” Tallant observed. And while there have been some unique considerations on Appomattox, “here again, we’ve been able to standardize where we could, and we have reduced our drilling costs significantly.”

A key cost-saving feature on Appomattox was the elimination of a platform rig, which has enabled Shell to realize considerable space and weight savings on the host facility. Production will take place at the subsea drill centers and wells. “Putting a platform rig on there becomes almost too challenging. The weight and space that you need to do that becomes difficult. The strategy there is to produce everything back from a subsea into a single host, and to do that as efficiently as possible,” said Tallant.

Shell has also been able to reduce some of its subsea costs as well on Appomattox, particularly in its export systems. “In many ways, we’ve had to revamp a few things, but we’ve made unexpected progress on reducing costs on Appomattox, even during project execution.”

The sanctioned project includes capital for the development of 650 MMboe resources at Appomattox and Vicksburg, with start-up estimated around the end of this decade. A tieback from the Vicksburg field to the Appomattox platform is already planned, and a tieback from the Gettysburg field is being reviewed. If this field is tied back to Appomattox, it could bring the total estimated discovered resources in the area to more than 800 MMboe.

With the recent completion and arrival of the hull in Texas, and construction of the host platform and fabrication of subsea infrastructure currently underway, the Appomattox project is more than 65% complete.

Shell sanctioned that Appomattox project in 2015. Before that, Tallant noted, “we were able to reduce capital by about 20%. But, since then, we’ve reduced it by another 20%. And it’s the same thing – it’s about being more efficient in your design, your scope, and working to bring your drilling costs down.” Taken together, Shell has been able to bring break-even prices on the Appomattox project down to levels that are much more competitive in the current market.

The first phase of the Kaikias project will include three wells tied back using a single flowline to the nearby Shell-operated Ursa production hub.

Looking forward

In addition to Appomattox and Kaikias, Shell is also advancing Coulomb Phase Two, a brownfield re-development project that has the potential to extend the field’s productive life by at least 10 years. Located in Mississippi Canyon blocks 657 and 613, the original Coulomb field was first placed online in July 2004.

Phase Two consists of a subsea system that will tieback to the Na Kika production hub, a new well, and a new module on the platform’s topsides to accommodate additional hydrocarbons. The well was drilled in more than 7,500 ft of water, and was completed in early 2016. By competitively re-designing the well, Shell says it was able to achieve significant cost savings without compromising safety. This and other measures have enabled the company to bring the project’s break-even price below $40/bbl. First oil from Coulomb Phase Two is expected by the second quarter of 2018.

Looking forward, Vito is Shell’s next project in the deepwater Gulf. Located in more than 4,000 ft (1,219 m) of water in Mississippi Canyon block 984, a study is under way to determine the floating platform design that will best optimize field development, in a low oil price environment. The Vito host will initially handle production from the Vito subsea field being subsequently developed, with potential for future tiebacks from other fields.

The study is still being reviewed, and Shell engineers are hoping that the project will be sanctioned in 2018. Supporting that final investment decision will be the fact that company planners and engineers will have been able to employ this new lean philosophy throughout the project. Vito will employ a smaller host facility, Tallant explains, as well as a single processing train system. “It will also use single lifts, rather than lots of different modules that you have with a normal TLP or FPS,” Tallant said. “So, it’s using a lot of things that we’ve seen from smaller independents, and it’s bringing capital costs down quite a bit.” Like Kaikias, Vito will have a break-even price below $40/bbl, a remarkable feat for a major deepwater project. Like Appomattox, Vito will feature a semisubmersible host facility. But unlike the Appomattox host facility – which was sanctioned before the downturn – the Vito semisubmersible will be designed and optimized for the current price environment, says Tallant.

“When it comes to staying competitive in the business climate we’re in, it’s an all-of-the-above approach,” Rajasingam observed. “It’s not just about technology. It’s not just about efficient execution. It’s not just about end-to-end thinking. It’s about all of it, and how you put it all together with a coherent understanding of what your business objectives are. You have to make sure that what you’re doing directly links to the bottom line. This approach has really helped us tighten up and get lean and focus on our commercial and business objectives, and then fit all the solutions that help drive that in place. So it’s all about being focused and integrated in the way you approach the challenge. That approach has helped us stay competitive and get even leaner and fitter.”