William Furlow

Editor-in-Chief

The goals seem sound – increase trans-parency, level the playing field, make bidding on projects more competitive – but the trend toward online bidding has some contractors worried that operators don't see the whole picture.

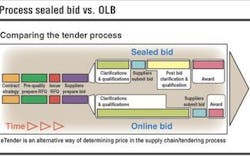

Online bidding follows the same basic format as a normal tender process. The operator develops specifications for the item or service. The potential vendors are evaluated and pre-qualified. The operator issues its tender documents, which include a comprehensive set of bid rules. The technical and commercial terms are submitted by the qualified bidders and are evaluated by the operator as would usually be done. Then the bidding begins. Once the bidding concludes, the approval process follows. The bid results are sent to the tender board and partners for approval. Following this, the contract is awarded.

The difference

To bid online, each qualified vendor receives access to a website and a coded user name. At a pre-designated time, the contractors begin bidding on the job. Each can submit as many bids as desired within the time frame of the bidding, usually a few hours. All the companies can see the other bids, though not the names of the bidding companies. Once the bidding closes, the low bid wins the contract.

Online bidding for commodity-type products has existed for some time, but recently it expanded to include complex engineering projects. Ken Arnold, CEO of the Paragon Engineering Companies, says his company does not participate in these reverse auctions because there are too many intangibles to make the bidding fair, and because this type of bidding precludes the engineering company from being professional and looking after the best interests of its clients.

Before bidding begins, the operators harmonize the technical and commercial terms of the contract, which gives the companies bidding a clear understanding of the scope of the project. They should also have a clear understanding of the work and materials before bidding.

The bidding process

The operator sets a minimum bid below the estimated cost to the contractor as well as a ceiling price to kick off the process. Arnold said he has tracked trends in these bids and found a pattern. The bidding usually starts off slowly, with one company inevitably bidding the ceiling price, and then it falls as the others begin to compete. The bidding generally plateaus near what the contractors have all estimated they could do the job for, including a healthy profit margin. It will sit at this level until the bidding has almost concluded. Then the bids will once again drop dramatically. Arnold said this is when the contractors decide if they would rather have the work or make a profit. If a fabrication yard is empty, the contractor might prefer to have a marginally profitable job that keeps his people working than nothing at all. There is also the risk that these bids are being made with the idea that some of the loss can be made up once the project begins.

There are ways to cut corners or add work to a project. These can protect a company's bottom line. While not good business for the contractor or the operator, it is a fact of life, Arnold said.

Win-win scenario

It is common for operators to form alliances with key contractors or have preferred vendors for certain equipment. This ensures the operator can get the equipment or services it needs on time and receive after-sales support. The vendor or contractor, on the strength of such an arrangement, has the confidence to stock replacement parts and service personnel to support the contracts and is able to act quickly to meet the operator's needs. When those needs change, it is advantageous to have an informed contractor to assist in designing for these changes. This guarantees the operator a reliable source for its most essential equipment and the contractor a continual source of revenue.

The problem is, while online bidding cuts costs for the operator and introduces even more competition among service and equipment providers, it flies in the face of a win-win policy. The reverse auction not only pits contractors against each other on price, but also spreads an operator's work around so that there is no longer a symbiotic relationship.

In dealing with standardized products, Arnold said, all the bidding companies are on an equal footing, and the operator can focus on price alone in making a decision. When dealing with engineered equipment, it is difficult to account for quality differences among vendors. The operator is not obligated to take the lowest bid, but the process has no way to account for such intangibles as the vendor's existing relationship with the operator, maintenance history, flexibility, deliverability, and reliability. For example, one vendor has a history working with the operator on a certain engineered product, so the vendor stocks spare parts, has maintenance people on staff, and knows how the product will fit into the operators overall design.

What is the value of this in terms of bid price? Arnold argues that the advantages of using an existing vendor are already built into the decision-making process, but are lost in the online bidding model. In highly engineered equipment, there is a certain amount of judgment used to determine if the vendor can deliver the required equipment on schedule and then support and maintain it once it is installed and operating.

These intangibles should be addressed in the pre-qualification phase of the online bidding, but Arnold said these decisions come down to engineering judgment on the part of the operator. While these services can be reduced to nothing but price, operators have to quantify the value of a relationship with a vendor because they will use different vendors, depending on price, for each product they buy. There is a disconnect between the online bidding process and a mutually beneficial operator-vendor relationship.

Another issue is the estimate the vendor uses to bid on the job. These estimates have built-in contingencies that cover unexpected costs during the job. On top of this is the profit built into the bid. If the winning bid requires a vendor to remove this contingency and even the profit from the job, the bidding becomes so cut-throat that no one makes money.

This pattern could go on for a while, but eventually it will cause yards to close and vendors to go out of business. Reducing the number of vendors will lead to less competition and an adversarial relationship between suppliers and their clients. A supplier who needs to derive extra income from a job to stay in business and who knows relationships don't matter will normally be able to maneuver a client into added work not covered by the original contract, at some cost to the project schedule.

Low risk/high risk

Jim Renfroe, senior vice president for Halliburton's Fluids Division, said online bidding makes up a small percentage of the projects his company bids on. Most online bidding has been set up around what Renfroe calls "low-risk" products and services. Low risk in this case means that if the product or service fails to deliver, it will not cause major problems for the customer. These are what most companies consider commodity products, where there is little difference between brands. On this level, Renfroe said, it makes sense for the operator to look for the lowest price.

On higher risk products and services, the customer should look at a range of factors in addition to price as failure of such equipment could cost the customer much more to fix than was saved in the bidding process.

Even so, Renfroe said, a number of major operators are testing online bidding for higher risk products and services. These include directional drilling, stimulation services, and complex well design work. In a traditional tender offer, a number of factors come into play before a bid is accepted. In the online auction, the sole consideration is price. The operators do pre-qualify bidding companies, Renfroe said, but in several cases the winning bidder had little or no experience in the field for which the bid was won.

It is not uncommon for the operator to include a few smaller companies with little experience in one of these auctions in the hopes that their bids will help drive down the price. If it turns out that the company with the winning bid is unable to fulfill the contract, the operator is under no real obligation to use them. It is simply a matter of going to the next lowest bidder. By the same token, if the company that wins the bid realizes after the fact that it bid too low and cannot perform the work for the price quoted, it is possible to get out of the bid. In this way, the operator risks little in including smaller, less experienced companies.

Those involved in the bidding are receiving less and less information during the process, Renfroe said. In earlier bids, there was a certain amount of transparency. All bidding companies could see each other's bids, though the companies were not identified by name. In more recent rounds of online bidding, the only information provided is the status of the individual company's bid. In experience, each bidder is told whether or not his is currently the winning bid, with no idea of where the other bids lie. Obviously, this could lead to a number of problems for service companies.

If a company is not careful, Renfroe said, the structure of online bidding can create a sense of urgency and lead bidders to make irrational decisions they might later regret. To protect itself, Renfroe said, Halliburton, which does participate "reluctantly" in these reverse auctions, will simply bid what it considers to be its best price and not compete beyond that. While this avoids many of the pitfalls brought about by the online bidding process, much of what Halliburton, and the other major service companies, provide to customers is not taken into account by this process.

R&D efforts

Service companies that devote a lot of time and resources to developing new technology, as well as integrating and supporting their products and services, consider comoditization of services a dangerous trend. While R&D may be looked upon as intangibles, they can make a big difference in complex jobs where the operator has a lot at stake.

Service companies have been able to distinguish themselves by customizing their services and products. Renfroe said the major service companies invest a lot of effort and money to ensure availability and reliability. This effort flies in the face of the online bidding model because the services and products offered by these companies are, by design, not interchangeable. A big part of what a customer is buying is the reputation and expertise of the service company. This value cannot be factored into a process that is based solely on price.

While the procurement offices of operators might enjoy the cost savings brought about by these competitive online auctions, Renfroe said, he doubts the process is popular with operations personnel. These people implement the programs and working with the winning bidder.

OLB evolves

Online bidding (OLB) was "spawned" in the manufacturing industry driven by business use of the Internet in the mid '90s. The electronic reverse auction (E-RA) part of the OLB process was designed around the sourcing of parts and products. Commonly supplied items were more easily "commoditized" for best-price-based awards. E-RAs simply set the stage for marketplace competition to fairly and voluntarily drive each bidder's price to "free market" levels. When a participating supplier saw his bid for producing a 1,000-unit lot of widgets undercut by another pre-qualified supplier, he could respond by re-bidding at a slightly lower price. Price transparency made this marketplace learning and price justification process possible.

Over the next few years, OLB practices evolved into more complex tenders. Complex products and services and combinations were OLB and priced via E-RAs. More market push-back occurred due to the complex or partially defined scope of supply. Concern over e-buyers not valuing past relationships, track record, quality, and reliability exists. E-RA gadgets such as transformation factors helped create better "apples-to-apples" comparison in some cases. Smart or transformation factors are now used to value tangible and intangible factors that affect implemented price. This should normalize the buyer-set factor or adder back to bid price.

In other cases, the complexity of the tender, involvement of multiple subcontractors, and short associated bidding timeline made it next to impossible to normalize everything back to price. Many OLB service and software providers are working on the next generation process where multi-staged, multi-parameter bidding will occur. This would be similar in structure to the large EPC offline sealed bids. In this fashion, price, schedule, risk, and other items critical to quality can be methodically evaluated in a funnel-like approach. It is believed each supplier's total value proposition will be better evaluated so better decisions will be made.

John Skinner, program manager, E-Business for Halliburton KBR, said he anticipates online bidding to become more prominent in the offshore sector over the next few years. The opportunity to achieve significant budget savings without sacrificing quality or safety is too appealing for most shallow and deepwater operators to ignore.

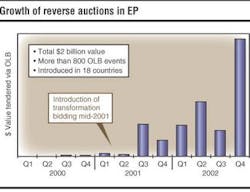

While OLB usage has gradually grown over the last four years in the operations and maintenance and onshore petrochemical industry markets, Skinner anticipates a faster ramp-up offshore. Because much of the risk in such reverse auctions has been proven out in larger onshore auctions, it will pave the way to initiate at a higher level for offshore online auctions. From a regional standpoint, Skinner said, operators in the North Sea and Southeast Asia regions are early adopters of this method. Shell is leading the charge by operators. Most other supermajors appear to be trying to catch up with Shell's quantity and dollar value on "reverse auctioned spend." These other companies, including ExxonMobil, BP, Marathon Oil, and ChevronTexaco, are making bold moves that indicate this trend will continue to grow.

For example, Dupont has announced it will use online reverse auctions as its default method of soliciting bids. Exceptions will be made on a case-by-case basis, but Skinner said this will account for hundreds of millions of dollars in online bidding.

Dupont works directly with the onshore and operations and maintenance sectors, but Skinner said the process has been proven up for the offshore oil business. The escalating tender values being auctioned indicate growing confidence in E-RA. Three years ago, a $40-million line pipe E-RA was record-making. Now, multiple product and service-based tenders exceeding $100 million have been run.

While reverse auctions are an obvious choice for select commodity products and services, Skinner said, there are sophisticated processes in place and being developed to help buyers better understand such tangible and intangible factors as reputation, experience, and safety record when selecting among vendors.

Skinner should know; he comes from one of the companies that develops the auction software and supports these activities. His role at KBR includes internal consulting to ensure the company protects its interests and makes the most of its participation in these auction events. It is clear that there are many potential pitfalls in online auctions both for the buyer and seller. Skinner said he was involved in occasional E-RAs, from a supplier consultant's viewpoint, in which the buyer planned to reverse auction the wrong tender or a potentially appropriate tender in the wrong way or at the wrong time. In one example, the buyer hoped to improve on an existing deal with an incumbent vendor. The vendor had an on-going contract that was up for renewal, and the buyer wanted to test the waters. It turned out that there was not that much competition for the work, and the current vendor easily won the bid for a higher rate than called for in the current contract.

Skinner said such a problem can easily be avoided by setting maximum or ceiling bid limits or a reserve price limit, but companies that rush into the online bidding market occasionally lack experience and training to avoid such problems. In other cases, unclear rules of engagement or weak communications or interface management are the pitfalls.

On the other hand, Skinner has been involved in many E-RAs where the buyer was able to improve substantially on what was considered a vendor's best offer by putting the contract out for bid via E-RA. For example, Skinner managed a number of successful line pipe reverse auctions where savings over pre-existing, long-term contracts exceeded 4%. For this tender type, the savings is considered great. Savings associated with more complex tenders tend to be higher. E-RAs on wellhead (wet or dry tree) supply, for instance, averaged over 20%. Many service-based tender savings average over 15%. Determining "what's hot and what's not" savings-wise depends on marketplace timing, knowledge, and OLB experience.

Skinner said his job becomes more complex when a buyer tries to "reverse handicap" bids based on the bidder's qualifications. As with any tender offer, specs are circulated to a list of pre-qualified bidders. Skinner said there is always a period of negotiation in which exceptions and qualifications are requested by the bidders. The vendors will review the requirements and call with questions or suggestions on the scope or language of the contract. Qualified bidders often see elements in a job that the buyer missed. Pointing these out ahead of time, can resolve questions and avoid costly changes. Skinner said the better or "tighter" the bid package, the fewer misunderstandings and resulting change orders. This saves the buyer both time and money and ensures the job is done right.

The process of weighing contractors' capabilities in a bid is called "transformation," Skinner said. A number of software packages offer this capability. There is always the temptation, by the operators, to save time during the internal evaluation and simply shop price to see "how low will they go." Some feel the ISO 9000 and other QA/QC programs implemented by contractors in recent years have helped justify price-based awards. Although buyers say price is not always their primary concern, allowing contractors to other bids creates a lot of cost pressure.

In the case of KBR, Skinner said, the company has a defensive online E-RA strategy and process. It was deployed for risk mitigation and business development purposes. Before the auction event, KBR evaluates the scope of a project and the internal costs associated. Skinner said KBR determines its lowest allowable bid ahead of time and sticks with this. By educating KBR staff on the details of online bidding, Skinner said, he not only improves the company's odds of placing winning bids, but also ensures that the company can do the jobs with a healthy profit margin.

KBR and other major contractors are under pressure from operators not only to participate in large online bids, but also to use this process to select subcontractors for EPC projects. This puts the contractor in the position of either auctioning off these contracts, or explaining to the customer why they chose not to. In such a position, it is critical for the "e-enabled" contractor to work with the operator in designing the bid package. A properly designed bid package ensures the contractor who wins the bid can do what is required and avoid costly change orders. KBR provides internal training for operations personnel as well as the procurement groups, which actually conduct the auctions.

This gives KBR the opportunity to communicate with the buyer on specifications for the bid.

"It is in the interest of both the buyer and contractor to be clear on what is wanted," Skinner said.

Submarining

While there have been cases in the past where bidders have come in late in the auction trying to beat the lowest bid by whatever means necessary, Skinner said, this is no longer that common. The thinking originally, by smaller companies competing with the major integrated service companies in online auctions, was that if the larger company bid a job for a certain amount, it stands to reason the smaller company could beat that price because it had lower overhead costs and did not insist on as high a profit. Skinner said these companies assumed they could successfully outbid the larger players and would not spend the time and money to properly engineer their bids. As a result, many of these submarine bidders, as they are called, won the auction, but were not successful. If they were awarded the work, in many cases they lost money on the contract, damaged their relationship with the client, or both. With more experience under their belts, these companies don't make the same mistakes they once did.

Transformation factors

Skinner said that if the buyer is open about the use of a transformation factor, then it allows the bidders to argue their "total value proposition" case beforehand. Many of the auctions are set up so that the bidders know about the transformation factor but not what the factor is. Setting these factors properly requires involving the operations team as well as the procurement group because there are so many technical considerations. Also, the operations team will have to work with the winning bid, either as a service or equipment provider, so their experience with a particular vendor is relevant.

Another approach is to do all of this evaluation after the fact, looking only at the low bidder(s) to determine which company is best qualified to do the work and has the ability to do it for the price quoted. The bottom three bidders, for example, may be evaluated in such a manner post-bid because the price difference between each is typically small. The bidding companies are informed that the low bids will be reviewed before being accepted. The problem here is that the bidder is at a disadvantage because of not knowing if his bid will be accepted at face value, or using a transition factor, determined after bidding concludes. Likewise, there is a possible disadvantage for the operator. The operator may not receive the lowest possible bid if the bidding companies assume reputation or change-over cost will support a higher bid. Of course, these same limitations exist on traditional sealed bids, but the goal here was to create something better. Skinner said this process is an improvement over sealed bids but still has to evolve for the more complex tenders involving highly differentiated suppliers.

An operator's perspective

David Conway, supply chain director for Shell EP, said his company first explored using reverse auctions in 2000 as part of a wider eProcurement initiative. Shell considers online bidding as a transparent means to determine the fair market value for products and services. Conway said OLB should not be confused with transactional e-procurement, which includes buying online using catalogs. Shell has made a number of advances in the course of conducting 3,800 OLB events totaling $4 billion in value. OLB is a tool that can be used, in appropriate circumstances, to gather the pricing element of a tender online.

Although the initiative was launched in 2000, OLB didn't really take off until a year later, when the software designed for these applications caught up with the needs of the industry. Specifically, Conway cites the transformational ability, which levels the playing field among various vendors. These transformation factors should be considered in any type of tender, but in an online bid these have to be evaluated before the price is known. This cuts right to the heart of the OLB process. A major benefit for both parties is the requirement for clarity as to what's required and on what terms it's supplied, before the price is determined.

As complex bundles of products and engineering services are let online, it is critical to ensure that suppliers are carefully screened and the scope of their abilities scrutinized. This is done internally, and the bidding companies are normally told what the transformation elements are, but may not be told what their specific transformation factor is.

To protect supplier-pricing confidentiality, suppliers see only where their current transformed bid sits relative to the others, whose names are not visible. When they make a new bid, they do so in relation to their previous bid. Basically, the companies are given an opportunity to see where their initial offer stands, by receipt of instant online feedback, and have the opportunity to reconsider their position and offer a more commercial bid as often as they choose. In a traditional sealed bid scenario, this is not the case. Conway points out that the transformational process has always existed in a traditional sealed bid process, but the vendors never knew where they stood until they either won or lost the bid. Even if they lost the bid, there was no transparency with regard to where their bid stood in relation to the competition.

Shell contracting and procurement teams manage these events internally, using a third-party service provider to host the event (software) and provide system support. The service provider also has a role in enforcing certain bid rules and provides extra assurance to proper behavior during events, including an audit trail. Shell's procurement team controls the OLB process, including establishing the structure of the bid and inviting selected companies to participate. The team members are co-located with Shell's operations to assist the project teams across the globe. There is a small centralized "expert" team that records and distributes best practices and learnings from the different tenders around the world, assuring process integrity and sustainable delivery of business results. Within business ventures, tender boards ensure the tender strategy meets business needs, is conducted with high integrity, and that the award decision is in line with the agreed process.

From a corporate perspective, Shell sees a number of advantages to OLB: the transparency of an online bidding event highlights the integrity of buyer's sourcing decision; the process promotes timely award of contracts; and suppliers have access to the global buying community with the opportunity to gain business in new areas. Conway reiterates that the process establishes the true market value for goods and services. Shell has conducted online bidding events across all its major businesses for many commodities and services, varying from promotional materials to complex construction to integrated service contracts.

The decision to use OLB, as opposed to the traditional sealed tenders or negotiation, is based on the business needs and the specific supply market. In cases where a number of qualified vendors are able to fulfill the needs of a well specified contract, OLB would be considered as an option. If a project team decides that OLB is the way to go, then there are guidelines and a well-defined process standard with high integrity and quality assurance. A major component of these guidelines is the transformation factors and engagement with the various suppliers prior to the bidding. This communication ensures they are clear on the specifications of the bid and structure of the event. Shell also provides training for the suppliers so they understand the mechanics of online bidding, well before the actual OLB event takes place.

The transformation factors used vary depending on the scope of the job, the geographic area where the work will be done, and the type of product or service being bid. These factors are developed by the project team and may include: Shell's confidence in a supplier's ability to deliver the product or services on time; the cost of mobilization; risk; ability to apply proprietary processes or technology; terms; and conditions and payment schedules. The pre-qualification, technical tender, and clarification processes are the same as used in traditional sealed bids. The qualification process is designed to be familiar to the bidding community. The only special training needed is to become familiar with the specific software used in the online bidding event itself.

Conway said that, compared with the traditional bidding procedure, there is increased transparency built into the OLB process. The bidders know the scope and requirements, understand the transformation considerations, and understand the award criteria of the bid. Properly managed and applied correctly, online bidding improves the process of awarding the contract, which benefits both Shell and the bidding community.

Established principles are part of this process:

- Always consider the full value of supplier offerings

- Ensure quality supplier engagement

- No price negotiations following an OLB.

The research that goes into the front-end of this process is disciplined, which, Conway said, allows Shell to reward value added by various bidders.

"To ensure best value from Shell's $30-billion annual spend on goods and services, we recognize the need to have sustainable long-term supplier relationships based on performance and value delivery. Although an online bidding event is a new way by which to gain competitive pricing, it does not replace, in any way, the necessary contract performance and supplier relationship management. We count on the continued capability, innovation, and performance of our suppliers and are always looking for ways to improve our supply chains to the benefit of all parties," Conway said.