The last decade has seen vessel requirements in the offshore wind market change dramatically. Average turbine sizes in the European market have grown from around 3 MW in 2010 to 8 MW last year, with an average turbine size of 12 MW expected in the region by 2025.

Wind turbine installation vessels

The rapid increase in size and height of offshore turbines has seen the wind turbine installation fleet (WTIV) struggle to keep up. Vessels delivered at the start of the decade are now either finding themselves relegated to the sidelines of the market, carrying out maintenance scopes, or being forced to carry out significant crane and deck upgrades in order to remain competitive. The short lifespan of the first generation of WTIVs had previously made vessel contractors wary of committing to newbuilds, but the rapidly approaching shortfall in WTIVs capable of handling the largest turbines on the market – coupled with the globalization of the offshore wind market, with new areas such as Taiwan, Japan and the US opening up – has finally seen a rush of newbuild orders.

Excluding the Mainland China fleet, IHS Markit’s ConstructionVesselBase currently tracks 16 WTIVs, although due to their size and technical capabilities, several of these units are now only expected to work in regions or on projects which still require the installation of smaller turbines.

To date, commercial-scale installation of turbines has only been carried out jackup units; but in a move which may open the door to other installation methodologies, particularly for projects with difficult seabed conditions, Heerema’s heavy lift semi, Thialf, will install 27 of Vestas’ V174 – 9.5-MW turbines at Parkwind’s Arcadis Ost in the German Baltic Sea in 2023. Despite the potential innovation of turbine installation from a semi unit, contractors and investors remain focused on new generation jackups, with nine units ordered since 2019 – including three this year. Only one Jones Act-compliant unit, however, Dominion Energy’s Charybdis, has been ordered to date.

The rush to meet turbine installation demand has not only seen seasoned players, such as Jan de Nul and Cadeler (formerly Swire Blue Ocean) put their cards on the table and order newbuilds, but also the entrance of newcomers into the market. OIM Wind, Offshore Heavy Transport (OHT) and Eneti are among those vying for a slice of the turbine installation market. Since ordering its newbuild unit earlier this year, Eneti has also confirmed it is contemplating targeting the US market with a Jones Act compliant newbuild.

Meanwhile, the rush to upgrade and extend the working lift of existing units is on. As well as its two newbuild units, Cadeler will also upgrade the cranes on its Wind Orca and Wind Osprey, with work expected to be complete by 1Q 2024. Meanwhile, Fred. Olsen Windcarrier has brought forward its planned crane upgrade for Bold Tern to this year, with the Brave Tern also scheduled to have a crane upgrade. The rush for newbuild WTIVs may also not quite be over – as well as nine vessels under construction, ConstructionVesselBase is currently tracking a further 14 potential newbuilds, with several of these options of under construction units.

Foundation installation vessels

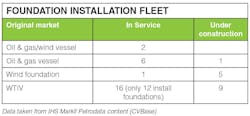

The industry acronym of WTIV is of course slightly misleading when we consider that according to ConstructionVesselBase’s historic data, this fleet, excluding Mainland China, has spent around on third of its installation time on foundation installation work within the offshore wind market. ConstructionVesselBase currently tracks 21 vessels capable of installing foundations at the moment, excluding Mainland China vessels. Of this fleet, 12 are WTIVs, while there are a further nine units considered only capable of installing foundations in the wind market. Unlike the turbine installation market, which has to date only seen jackup units install turbines on a commercial scale, heavy lift semi and monohull vessels such as Boskalis’ Bokalift 1, the Seaway Strashnov, Seaway Yudin – and latterly, the Saipem 7000 – have all carried out foundation installation campaigns. Of the nine foundation installation vessels, six are considered as mainly oil and gas vessels by IHS Markit, with two vessels working equally across both markets and one vessel considered as a foundation installation specialist.

While all the nine WTIV vessels under construction will be more than capable of installing foundations, the newbuild orderbook has seen contractors also realize a gap in the market with the advent of larger monopile and jackets, required for deeper waters and larger turbines. Currently, there are five “specialist” foundation installation units under construction, with a further oil and gas vessel that may also cross over into the wind market. While heavy lift oil and gas vessels have sought work during the downturn in their original industry, it might be considered that these vessels may in future struggle to compete against specifically designed units with huge, maximized deck spaces for monopiles, and may have to target nearshore projects which do not involve lengthy round trips to port, when a vessel’s carrying capacity will really come into play.

SOV fleet

The increasing size and distance to shore of offshore wind projects, particularly in the maturing European market, has also seen the rise of the service operation vessel (SOV). For a vessel type which has only really been in existence for around a decade, business is booming. Generally, turbine maintenance for smaller, nearshore projects is carried out by crew transfer vessels. But factors such as transfer times, crew comfort, and the pressure to keep larger turbines operational at all times has driven the market for SOVs on larger, far-shore developments. The SOV market remains focused in Europe, with only two SOVs – one destined for Orsted in Tawian, and one for the US – being built for non-European projects.

Currently there are 29 SOVs in service, all located in Europe, with a further 14 under construction and a further seven potential builds. The majority of these vessels are built to order for long-term maintenance contracts across one or more wind farm. And the majority of these are newbuilds, with only seven converted subsea or PSV vessels across the fleet. The relatively low build cost of a newbuild is around $56 million (EUR 46 million) is helping to drive the market for newbuild SOVs. From a utilization point of view, the success of the fleet is clear, with utilization hovering just below 80% for 2018 and 2019, and above 80% for last year, although the gamble is on the contractor agreeing to a fixed rate for a long-term contract which could last five, 10 or even 15 years.

Conventional oil and gas construction support vessels (CSVs) have found a comfortable niche in the European offshore wind walk-to-work market (W2W), and compete against SOVs. They mainly provide support on the capex side of projects, working on short- to medium-term contracts, or act as a “front-runner” vessel to the long-term opex vessel. However, although walk-to-work/SOV demand has increased year-on-year, the percentage of W2W days carried out by subsea vessels in Europe has dropped since 2018, with this year’s recovery in oil and gas taking vessels out of the wind market. In addition, the movement of several of these vessels into the Asia/Pacific wind market has also narrowed the pool of available CSVs for wind work. While subsea contractors try to work out the odds between available oil and gas work and offshore wind scopes, more newbuilds for the offshore wind market are likely to be ordered before the year is out.