Dr. Roger Knight, Julian Callanan, Catarina Podevyn - Infield Systems Ltd.

Over the last few years, the upwards projection of the global economy has been so assured that the offshore industry has been running at fever pitch to ensure supply meets demand. With the price of oil soaring above previous highs, all aspects of the petroleum sector became attractive from an investors point of view, and funding for the most ambitious of projects was achievable. However, with the advent of the credit crunch’s two-fold sting of falling energy demand and stricter terms of lending, we start to see that some companies and business concepts are more adept than others in maintaining their momentum in troubled times. To illustrate this, Dr. Roger Knight, Julian Callanan, and Catarina Podevyn, of Energy Analysts Infield Systems Ltd., focus on the leased FPSO market, where potential growth is supported by strong long-term drivers, yet currently severe short-term financial challenges abound.

In tandem with many other areas of the offshore industry, the FPSO market has enjoyed strong growth over the last five years. Several factors have been pivotal in driving this process. Firstly, as acknowledged in the opening paragraph, demand for hydrocarbon energy has increased progressively, and, due to expanding populations and the wider trend towards individual consumption – railroaded only temporarily by the world recession – there is no reason to assume that this will not be the case in the future.

Secondly, looking at the sources of future supply to meet this growing demand, while investment in alternative energy sources continues (although the green message has dropped noticeably from the political agenda in the context of recession), fossil-based fuels retain their unchallenged position as the main energy source. This has been the case for some time now, and looks set to be the case for the foreseeable future.

Thirdly, arising from our established consumption levels of fossil fuels and their finite non-replaceable nature, many of the historically most prolific areas of offshore production, for example in the Gulf of Mexico and the Middle East, are viewed now as maturing, because the size and frequency of new discoveries seems to be decreasing, and many major fields are now beginning to post declining production levels. This, in combination with the diversification of energy demand away from the traditional US/European axis and conducive oil prices, has meant that previously discovered, but economically unfeasible, larger fields, typically located away from production infrastructure, have become viable. Finally, once this initial hurdle was overcome, a series of successful exploration campaigns in deepwater, coupled with exponential technological developments in subsea production, encourage the widescale proliferation of FPSOs as the development scheme of choice for fields without immediate access to production infrastructure.

As the FPSO market became more entrenched, and generous oil prices encouraged operators to look more seriously at developing smaller reservoirs, the leased FPSO market took off. A leased FPSO is a floating platform which is rented to an operator by a third-party for use on a specific field. An owned FPSO is a floating platform which is paid for and owned in its entirety by an operator. The rationale for using a leased versus owned FPSO is relatively simple, and is much like the decision to rent or purchase a property. If an individual were to live in a city for only a short time, it makes sense to rent, thus negating the requirement to raise large amounts of initial capital, and avoiding assuming as many liabilities as an owner would. If, however, an individual were to live in a city for a long time, renting a property still would continue to minimize assumed risk, yet there would be no potential for capital gains. For the owned FPSO, future capital gains can be achieved in turn through leasing the unit on, selling the unit to a leased FPSO company, or converting the unit back into a tanker hull and selling it to a transportation company. However, perhaps the most important rationale driving the decision to buy as oppose to lease, comes from the particular nature of the field itself, how this relates to solutions and associated charges presented within the leased market, and whether the operator is able to fund the capital required to own an FPSO. To continue the home buying analogy, should an individual have a specific wish list for their new property, for example wanting 10 bedrooms and a revolving roof, this is unlikely to be found on the rental market. However, if the individual has enough access to capital, then they will be able to fund this ambitious project themselves.

Looking at the current dynamics of the FPSO market, as shown in the graph on the previous page, we see close to an even divide between leased and owned FPSOs in the currently active fleet. This is a trend which we forecast to change over the next five years, as numerous projects made viable through previously high oil prices and advances in subsea technology come to fruition. However, after a string of recent shocks within the FPSO market, it has become clear that chartering leased FPSOs is not all plain sailing, and, as the offshore industry endures a flight to quality driven by now more cautious financiers, we are seeing the leased FPSO market, despite a promising last five years, becoming beleaguered with funding problems.

One such feature of current economic circumstance is project cancellations. Project cancellations can be either operator driven or contractor driven, as such they should not be confused with project terminations which are field and reservoir driven. Historically, project terminations have been much more prevalent than cancellations, with the operator’s right of termination often written into a contract on the grounds of poor field performance. As a result, a leased FPSO contractor’s day rate can be reduced to zero, or the leased FPSO owner could be faced with the prospect of compensating an operator for loss of production revenue. The structuring of contracts, as such, helps clarify the attractive risk mitigation operators receive when pursuing the leased FPSO option.

More recently however, we have started to note a growth in cancellations which have occurred in the negotiation stages of contracts, this is, in particular, a feature of the ongoing “credit crunch,” which has damaged, without exception, all business’s ability to borrow to fund further growth. Particularly acutely hit by this phenomenon has been the independent operator, and especially those with a limited existing asset basis who were tempted in to the offshore market by rising oil prices and the ability to leverage large amounts of debt against future production. This is, in turn, especially damaging for the leased FPSO market because many of these operators who are unable to independently raise enough initial capital to own an FPSO created much of the lease demand.

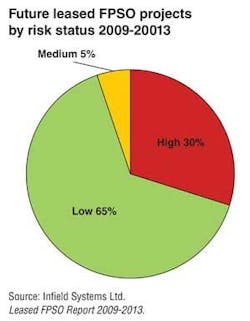

Australian independent Nexus, for example, canceled a contract in November 2008 with Vanguard relating to the Crux liquids development in the Browse basin offshore Western Australia, citing an inability for the two parties to agree on a final investment decision. A further example of operator driven cancellation, also in Australia, comes from the cancellation of an FPSO order by Anzon, now ROC Oil, with BW Offshore. The cancellation, in December 2008, again was blamed on the two parties’ inability to reach agreement on the terms of the project. Looking at the future nature of the leased FPSO market, as demonstrated in the figure below, we see a further 30% of all future leased FPSO projects scheduled to be installed between 2009 and 2013, as at a high risk of cancellation due to funding issues, should the banks not resume lending at previous levels. However, the majority of the market (65%) should be safeguarded by the resilience of the players active there, many of which are Super Majors. These large and still very profitable companies largely are insulated from many of the ravages of the credit crunch by integrated business models and generally lower project sanction prices. It is therefore anticipated that they will continue to honor their contracts.

One of the earliest outcomes of the credit crunch has been to encourage all players in the offshore industry to size up opportunity and risk more carefully, and to try to understand how robust their prospective clients’ business models are before entering into contracts. Leased FPSO contractors have been no different, yet many have been hit by growing illiquidity within the financial markets. Emas, for example, recently lost exclusivity on Premier Oils’ Chim Sao development after announcing it was struggling to secure the funding needed to proceed with the project. While Petroprod, based out of the Cayman Islands, recently was forced to sell two tanker units previously earmarked for conversion.

Funding problems have only been exacerbated by increases in conversion costs incurred by FPSO owners in fabrication yards. These were driven by the general increase in activity within the offshore industry before the economic crisis, and have since proven robust, although they now are starting to erode in sequence with wider price deflation. As there is no spot price for FPSO day rates, a fixed rate is usually agreed upon before conversion or modification commences. Therefore cost overruns considerably affect the balance sheet of contractor companies. This can be seen in the operating losses which Prosafe posted towards the end of 2008, which were accounted partly through the fact that the book value of three new platforms under construction was substantially higher than implied when determining day rates during the bidding stage, and, due to the depreciation of market value of the companies VLCC M/TTakama tanker. As a result, Prosafe was forced to write down the total value of its vessels by $196.8 million.

Most exposed to funding and cost escalation concerns are the speculative class of leased FPSO contractor. These are contractors who build FPSOs without prior contracts in place, targeting a quick, spontaneous market which made sense when the price of oil was above $100, yet now seems a little out of context. Infield forecasts that over the next five years as many as five new speculative units to be available on the market. However, these projects may be in some jeopardy, as the recent bankruptcy of speculative FPSO builder FPSOcean helps demonstrate. In early 2007, FPSOcean commissioned a unit targeted at small- to medium-sized developments in areas prone to hurricane or typhoon risk. By February 2008, after failing to secure a client for this vessel and, with the cost of conversion rising, FPSOcean was forced to take convertible loans – a tactic used to ease loan repayments, or regulate monthly debt. In addition, FPSOcean also was forced to abandon plans to convert the aframax unitSemakau Spirit, and sell it on to ease the financial constriction. Finally, by February 2009, after failing to attract new financing or win a contract for its Deep Producer 1 FPSO unit, despite entering talks with Majors and other leasing companies, FPSOcean was forced into bankruptcy.

The case of FPSOcean helps demonstrate just how difficult the current financial crisis has made life for the smaller companies active in the offshore industry. However, the long-term drivers of the leased FPSO market remain very positive, and for those who successfully win contracts, it is an industry which is very lucrative. Yet, without a return to the easy access to credit which typified the pre-credit crunch world, and, with the price of oil having fallen back to “normal” levels, we expect to see continued pressure on the smaller players active in the leased FPSO market. For those who are able to find safe harbors from the ongoing financial storm, the prospect of future global economic recovery, increasing energy demand, and fortified oil prices, acts as a light at the end of a long and arduous tunnel.