Operators increasingly looking for turnkey solutions

Anthony Caletka

Casey Carringer

PwC

Offshore exploration and production of oil and gas is one of the most prominent business activities across the globe. Capital projects such as offshore platforms, pipelines, and production facilities span from North to South America, Europe, the Middle East, West Africa, and Asia. For decades, billions of dollars have been invested in creating the infrastructure required to extract and transport these resources to global markets.

Many of these assets are now reaching the end of their useful lives. For the oil and gas industry, this end-of-life stage will involve reinvestment to extend operations; or the plug and abandonment (P&A) of wells, followed by decommissioning. Across the world, there are thousands of offshore structures and subsea systems in mature fields that will need to be addressed. This effort will require the cooperation of E&P operators, oilfield services (OFS) companies, and regulatory agencies – many of whom are now focused on this stage by necessity. The confluence of physical, regulatory, economic, and logistic difficulties makes decommissioning both technically and financially challenging.

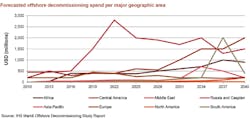

The world’s most mature offshore fields have already become eligible for large-scale decommissioning activities, and forecasts indicate that there may be as much as $200 billion in decommissioning spend across 20 markets through 2040. Shareholders, employees, taxpayers, and government bodies all have a stake in the game and will look to strategically navigate the financial, operational, and regulatory complexities involved in these capital projects.

(All images courtesy PwC)

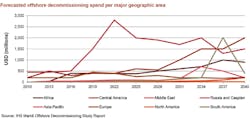

Six industry challenges

While not all issues will be relevant to operators, governments, and oilfield services alike, it is important to understand the relationships between these parties and how they are collaborating to help add structure and certainty to the decommissioning process. The following outlines six predominant industry challenges.

Portfolio management

Successful decommissioning programs require intense planning from strategy through execution. Forward-thinking organizations understand that this planning requires monitoring pre-defined metrics, such as return on capital employed (ROCE), against the timelines to estimated ultimate recovery (EUR) for each asset. Every E&P company has a different risk appetite, and each has adopted a trigger point that signals when an asset may be deemed “decommissioning eligible” (or “idle iron” as referred to in the Gulf of Mexico), based upon commodity prices, operating costs, and remaining reserves. Through this signaling, they have been able to understand the full range of options available for each asset including:

Selling the asset. We have seen a number of novel approaches in the past few years involving combinations of ownership/liability or license transfers – including some owners deciding to maintain full liabilities, transfer them to trust funds, or share liability with buyer(s).

In-house decommissioning.The advance notice of an asset’s end-of-life stage allows owners to assess the risk involved and satisfy the necessary front-end engineering and design (FEED), regulatory, and logistical requirements to estimate, plan and generally prepare for a smoothly executed project. Some have developed customized governance and stage-gating processes to usher these unique projects throughout the decommissioning process.

Turnkey decommissioning.Strategic partnerships are emerging in the service industry between OFS and EPCI companies to create holistic ‘one-stop shop’ decommissioning offerings.

On the other hand, organizations that have not clearly defined their decommissioning strategy or have not prepared in advance for unforeseen drivers, such as hurricanes, may not have the luxury of weighing these options. There are many examples of decommissioning projects that have experienced cost overruns, schedule slippage and contract disputes, resulting in eroded share price for all stakeholders involved.

Project excellence

Due to the infancy of the decommissioning services as an industry, there are very few historical benchmarks for the cost, schedule, and scope of these projects. Even looking to comparable markets is of limited value because each decommissioning market has varying depths, structure types, and climactic conditions.

Yet, the failure to accurately estimate the timeline and costs for a decommissioning project, or campaign, poses two specific risks to organizations:

• A recent PwC study found that 75% of companies experienced average share price deterioration of 12% within 90 days of reporting a significant negative capital project event – such as a project delay, cost overrun, or operability challenge.

• Asset Retirement Obligations (AROs) are a sizable portion of an upstream company’s balance sheet: Many of the supermajors have them in the billions of dollars. Uncertainty in delivering these projects could mean that significantly more funds will be required than estimated.

To combat these risks, organizations will need to focus on core project management capabilities such as forecasting, quantitative risk analysis to set appropriate budgets, based on risk and scope uncertainty, and “lessons learned” initiatives to promote continuous improvement and project excellence as they prepare for future decommissioning work.

The six key issues critical to decommissioning success.

Supply chain management

The inherent complexity of decommissioning capital projects requires many technical skills and roles – including operators, oilfield services, subsea diving, inspection, demolition, offshore construction services, regulatory representatives, and others. This level of participation yields increased handshakes, coordination and risks, as well as decreased margins of error for project execution.

Due to the lack of a sizable decommissioning market to date, service companies have not consolidated their services offerings to accommodate a turnkey solution. But this is changing. We see more offshore EPCI (engineering, procurement, construction and installation) firms providing jacket/topsides/subsea removal services, partnering with OFS companies who perform P&A work on the well and subsea infrastructure.

Depending on who you talk to, this fragmented supply chain will be either problematic or opportunistic. For the operator, the current state requires an increased level of project management as they deal with numerous third parties involved in the process. Project management costs on EPCI projects typically account for 8% to 12% of project cost, but decommissioning projects have added risks related to brownfield projects, discovery work and unknowns related to corrosion, hazardous fluids or structural deterioration manifesting both downhole and topsides.

Several operators have said they would like to see partnerships in the services industry that can provide consistent turnkey solutions but still allow them to maintain oversight of the operation. For forward-looking service companies, these gaps in the supply chain present opportunities to grow organically and/or inorganically to capture the addressable market. As an operator’s appetite for turnkey solutions grows, the service companies who can fulfill these holistic needs will see more opportunities to competitively bid for decommissioning contracts and eventually develop the level of client intimacy needed become a trusted decommissioning partner. These companies have already initiated market sizing, internal capability and inorganic growth initiatives in order to prepare for this opportunity.

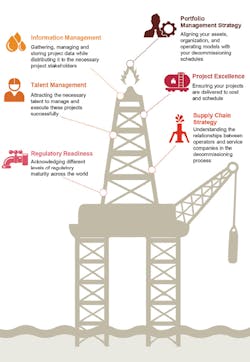

PwC’s Tableau-based GoM Asset Register.

Regulatory readiness

To add yet another layer of risk and complexity, operators with a global footprint will need to understand the various regulatory and technical standards in the regions where they operate. As fields mature at different rates, the regulatory bodies providing governance are also evolving based upon the imminence of these decommissioning “waves.” While many used to believe that decommissioning would be deferred and that activities would continue to be pushed out into the future, recent events suggest that governments are preparing to hold operators more accountable.

In the past two years, we’ve seen the following activities:

The United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) recommended that the Department of Interior complete plans to revise its financial assurance procedures to address risks posed on operators by these procedures. The GAO calculated approximately $38 billion in remaining liabilities in the Gulf of Mexico based on current standards and cost estimates.

Abolishment of the UK’s Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) as the Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) transitions to manage decommissioning programs with the Oil & Gas Authority (OGA).

The Russian National Ministry of Energy issued an RFP for an assessment of decommissioning obligations of offshore fields in Russia. This RFP includes analysis of cost, schedule, and scope estimates for decommissioning projects in the region with benchmarking analysis based on international practices.

A Netherlands Masterplan for Decommissioning has been drafted to establish 1) an organization to facilitate the Dutch decommissioning agenda, 2) a national decommissioning database with integrated scope and timelines, 3) effective and efficient regulation with regulators, and 4) a “lessons learned” initiative across projects for continuous cost and performance improvement.

Globally, we are seeing governments beginning to adopt best management practices, quantify and interpret presumed decommissioning exposures through probabilistic cost estimates, and collaborate with industry to determine viable decommissioning alternatives (i.e. the Rigs to Reef program in the GoM gaining international notoriety) with the dual mandates to safeguard their environmental assets and taxpayers’ dollars.

With this in mind, operators who can tailor their decommissioning programs to comply with government directives while minimizing costs are best positioned to separate themselves from their competitors.

Talent management

The lifecycle of offshore assets and fields is long, and there is a wide spectrum amongst operators in terms of internal capabilities for managing the decommissioning efforts. We’ve observed some organizations with entire decommissioning business units and others with only a few dedicated members embedded in a cross-functional team. While this can be dictated by asset mix and scale, there is no doubt that operators will need adequate resources to execute their decommissioning obligations.

One key decision operators will need to make is whether or not to outsource decommissioning projects. Those looking to remain lean will opt to allow service companies to perform much of the work while maintaining some level of project oversight; others will choose to have experienced, dedicated teams that can move across regions to efficiently develop, oversee, and execute decommissioning projects.

With regards to attracting talent, operators will need to combat negative notions about careers in decommissioning – such as decommissioning is the oilfield equivalent of “taking out the trash,” as one of our clients often reminds us.

Information management

When offshore development increased in the 1970s, well designs, records, and logs were still on paper. Over the years, ownership may have changed hands, records may have gone missing, and even when records are available, the tests themselves have become dated.

The use of ‘digital twin’ technology, including drones and Lidar (Light Detection And Ranging) may be required to digitize existing infrastructure, in order to properly reverse engineer and scope the decommissioning sequence and timing to ensure that a project that complies with safety, environmental and regulatory constraints.

Few companies are willing to bet their projects on historical well data. In order to meet current regulatory and environmental standards, many of them must first perform a series of well tests to determine downhole conditions. The results of these tests often impact the scope and timeline of the P&A procedures necessary to meet statutory compliance.

For stronger visibility into execution and compliance, organizations have integrated project schedule, cost, progress, engineering and other data into project management and role-based project collaboration systems that provide “bit to boardroom” transparency throughout the decommissioning process. This ensures that project information related to the well, infrastructure, or subsea installations flows between functional groups, across capabilities, and up the organization to allow for effective risk management and decision support throughout execution.

Conclusion

Since decommissioning is a relatively new strategic business imperative, there is a wide spectrum of capabilities and talent required in upstream operators responsible for executing these projects safely and successfully. In addition, the third-party service companies involved are building their own capabilities and offerings across the decommissioning life-cycle.

Finally, increased government directives, domestic and foreign, have put added pressure on the regulatory and financial reporting as well as bonding requirements involved with decommissioning a well. These mandates have only heightened the obligatory nature of this capital expenditure for the world’s offshore well owners.

As go-green initiatives gather momentum, leaner-for-longer operating models take hold, and decommissioning becomes more impactful to operators’ performance and financial health, this stereotype may be overturned. Eventually, with the large wave of assets becoming eligible for decommissioning, the ability to manage these liabilities efficiently, and consistently, could be a competitive differentiator.

The authors

Anthony Caletka is a principal with PwC’s Houston office and serves as the Global Capital Projects & Infrastructure Energy Leader. He is a Registered Professional Engineer with 25 years of industry experience in engineering, construction and program management executing projects related to capital efficiency, field development planning and project delivery.

Casey Carringer is a senior associate with PwC’s Houston office and specializes in the planning, design, management, and delivery of capital programs in the oil and gas industry. He has served clients across all segments by providing advisory services related to operational excellence, portfolio management, and capital efficiency.