Since 2002, expenditure on work-class remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) operations has more than tripled.

Since 2002, expenditure on work-class remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) operations has more than tripled. Further strong growth is expected over the next five years - leading to a total market of some $1.46 billion per year by 2011. This is one of the findings of a new market study “The World ROV Report 2007-11,” produced by Douglas-Westwood Ltd. (DWL).

Offshore utilization and work-class ROV dayrates have increased dramatically over the past five years and stand at an all time high. Between 2002 and 2006 alone, the work-class dayrate increase was around 30%. DWL estimates that, in 2006, $827 million was spent on the operation of work-class ROV units worldwide - an increase of 86% on the 2002 value. DWL forecasts that this will increase by a further 76% to $1,458 million by 2011, more than tripling the market size over the 10-year period.

Regionally, DWL expects North America and Western Europe to account for the largest proportion of ROV activity - 50% of the total units expected to operate in 2007 are associated with these regions.

More ROVs needed

The report is based on analyzing demand drivers. The work-class ROV industry has seen strong growth driven by the high and sustained oil prices of recent years, and it is expect to continue. A result has been high levels of drilling activity and increased installations of subsea wells, pipelines, control cables, and other hardware. In addition, increasing underwater resources are required to service the growing numbers of underwater installations. Moreover, this is increasingly happening in water depths beyond the economic reach of manned intervention. This all manifests itself in the build of new drilling rigs and offshore construction vessels, all of which use ROVs in subsea operations.

By the end of 2011, over 120 new work-class ROVs will need to be built per annum to satisfy the dual demands of market growth and attrition of the existing fleet. Based on an average cost per unit, work-class ROV capex will increase from its 2006 level of $186 million to $247 million by 2011, an increase of 33% over the period. Cumulative expenditure is expected to be a little over $1 billion over the forecast period.

The world work-class ROV operations market 2002-2011 by geographic region for oil and gas.

While ROV operations can vary from the inspection of inland bridge supports to mine detonation and the detection of smuggled goods strapped to the underside of vessels at dock, DWL’s market forecasts focus specifically on work-class vehicles in the offshore oil and gas industry for a number of reasons:

1. ROVs in the defense sector are extremely difficult to track for obvious reasons. Demand drivers in this sector are complex, and there is very little publicly available information.

2. Eyeball (inspection) ROVs are cheap and, as such, number in the thousands over a huge range of industries from tourism to port authorities. No reliable information is available on the numbers currently operating, and quantifying these numbers in terms of dayrates and therefore operational value is not only not feasible, it is highly susceptible to error.

Market drivers

The global market for ROVs in the oil and gas industry is driven by a host of factors, many of which also apply to other onshore and offshore oil and gas markets.

Continuing growth in energy demand

The underlying driver for all activity is the growth in global energy demand, which, for the medium-term at least, means demand for hydrocarbons (predominantly oil and gas). Over the long term, the trend toward increasing energy consumption is clear. Global annual energy consumption has more than tripled over the past 50 years, driven mainly by demand growth in developing economies. The EIA has forecast that world annual oil consumption will grow from the present circa 84 MMb/d to 118 MMb/d by 2030, although there is concern about the capability to supply such demand levels.

Oil prices drive drilling

Over the last 30 years, there has been a strong correlation between oil prices and drilling activity. The major oil companies have become risk-averse, and despite present oil prices around $60/bbl, our studies show the economics of major oil companies’ offshore field development prospects still are being tested against $20-$30 oil prices. This cautious outlook means that if oil prices were suddenly to fall to $25, there would be little impact on the levels of new offshore field development activity.

Oil supply

There is likely to be a sustained increase in oil prices as supplies tighten in the run-up to the peak production year, now forecast by many to occur sometime before the middle of the next decade. This will impact deepwater developments to the extent that they will become more economically viable as the oil price rises. The move to deepwater heralds growth in the ROV business. Developments that were marginal at $20/bbl undoubtedly will be more vigorously pursued in an environment where the long-term expectations of oil price are $50/bbl and upwards.

Increasing supply from offshore

As onshore supplies diminish, the push offshore becomes a requirement for sustaining the increasing levels of demand for oil and gas. Around a third of world production came from offshore in 2006, a figure that will increase as production from deepwater fields becomes necessary. Clearly, an increase in offshore activity has a direct impact on the demand for ROV systems.

Offshore drilling sustained

Around 17,000 wells were drilled over the last five years with a slight dip in 2003 followed by a rise up to 2005, associated with rising oil prices. The forecast for the next five years is of an increase to over 18,000 wells. Consistently high levels of drilling activity ensure a healthy future for the ROV industry.

Offshore capex growth

Global offshore capex is forecast to grow substantially from $92 billion in 2005 to peak at $120 billion in 2010. This represents almost a doubling over the 10-year period. Increased offshore expenditure, especially on subsea equipment, will strengthen the ROV market, which is a necessary technology on subsea developments.

Offshore construction to grow

Offshore construction activity is another major driver for ROV demand and increasing numbers of construction vessels are coming into the market. These newbuilds tend to disproportionately boost ROV demand as they are mainly focused at the deepwater end of the market for which work-class ROVs are essential.

Growth in offshore drilling rigs

Numbers of both jackup drilling rigs and, more significantly, deepwater drilling vessels are forecast to increase to 2011. The deepwater fleet is expected to grow by around 60% over the next five years. However, a lack of construction capacity will mean a shortfall in rig availability, increasing dayrates for vessels and therefore ROV systems. Additionally, it is becoming increasingly common for high day-rate drilling vessels to employ extra ROV units for redundancy purposes - the latest generation rigs are beginning to see day rates of over $500,000. Time lost due to ROV failure can be economically disastrous.

Push to deepwater

Deepwater production is forecast to almost double before the end of the decade. Capex is expected to exceed $22 billion by the end of that period. The increase in deepwater production is perhaps the biggest driver for the ROV industry, as water depths pass the boundaries of human divers.

Growth in subsea technologies

At the end of 2006, there were 3,261 operational subsea wells. This is the result of a period of strong growth in the market, a 50% increase on the 2002 value of 2,175. By 2011, DWL estimates that there will be almost 6,000 subsea wells in operation, almost doubling the 2006 figure. Subsea production is a key driver in ROV activity as the vehicles are used to repair and maintain seabed structures.

Background

The last 50 years saw dramatic and rapid changes in ROV technology. After the first tethered ROV system was built in 1953 by Dimitri Rebikoff, the US Navy invested millions of dollars into designing remote systems, primarily built to perform deep-sea rescue operations and to recover lost ordnance from the seafloor. The CURV (cable controlled underwater recovery vehicle) system gained prominence after the successful recovery of an atomic bomb in 850 m (2,789 ft) of water off the coast of Spain, following an aircraft accident in 1966.

However, the majority of growth in the ROV industry came from its move into the commercial arena following the swift development of the offshore oil and gas industry of the 1970s and ’80s, the latter end of which introduced offshore developments too deep for human divers. ROVs had by that time become an essential part of offshore production. After adjusting to the dramatic decrease in oil price during the mid 1980s, development of ROV technology began to accelerate.

Acknowledgement

The World ROV Report 2007-11 is the latest in a series of business studies from Douglas-Westwood Ltd. DWL conducts commercial due diligence work for the financial community, and business research, market analysis and strategy work for the international energy industry in both the upstream and downstream sectors. Rod Westwood is an analyst for DWL and has contributed to a number of studies for private equity houses and investment banks, examining a variety of oil and gas sectors, onshore and offshore, particularly focussing on the global ROV and drilling markets. He is joint author of the new The World ROV Report 2002-2011. For information about the study, go online to www.dw-1.com

ROV definitions, activities

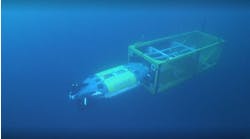

Remotely Operated Vehicles are electrically powered and controlled via an umbilical, maneuvering themselves in response to human commands with either hydraulically or electrically driven thrusters.

ROVs are classified roughly by the nature of the task they do. They are found on offshore platforms, support vessels, in nuclear power plants, in reservoirs, and salvage projects, and even submarine rescue situations. ROVs have the ability to “hover” and stay on location to perform a task.

The range of tasks carried out by the offshore industry that require the use of ROVs can be defined by considering the life-cycle of an oil and gas field, from exploration drilling (seabed inspection, valve operation, riser inspection, BOP hydraulics operation, etc.), to field development and production (platform and pipeline inspection, subsea hardware installation, infrastructure repair and maintenance) to decommissioning.

Work-class ROVs are equipped with manipulators and can have a variety of tools available (cutting disks, saws, etc.) via a removable “tool-skid” to suit a particular job. There are some ROV classed as heavy-duty due to increased payload and power availability, and also a “survey and inspection” class. The personnel operating and maintaining work-class ROVs must be highly trained as the technology involved can be complex.

Eyeball class ROVs normally are all-electric powered and have no manipulators or payload capacity. They are used solely for inspection duties. Eyeball systems are smaller, cheaper and simpler than the larger work-class systems, but are widely used in situations outside the offshore industry. They perform inspection tasks inside the cooling systems of nuclear power stations, investigate problems inside reservoirs and large tanks, and can be fitted with other sensors appropriate to the situation if required. Some eyeball ROVs are mounted on large work-class systems that they use as a local base, and for which they provide extra viewing capability during complex operations.