Henning Bjørvik, Rystad Energy

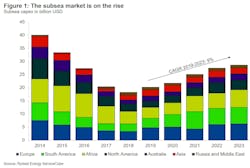

After four years of steep decline in subsea spending by operators, which eventually hit rock bottom in 2018, the subsea market has started its ascent. Fueled by a surge in deepwater sanctioning, Rystad Energy expects subsea to be one of the most promising oilfield services markets in the coming years. After 10% increase in capex from 2018 to 2019, the subsea market is poised for 9% annual growth in capex through 2023.

2019 will mark a turning point for the offshore industry, which has languished as a result of an oversupplied market and lower oil price. The paired production surge from OPEC and US shale pushed the Brent benchmark from above the $100 per barrel mark down to $50 per barrel in just a matter of months in 2014. The oil price has since taken the markets on a rollercoaster ride, with prices fluctuating between levels as low as $30 per barrel to as high as $80 per barrel.

As the oil price ricocheted lower and found a floor, operators were no longer able to justify capex on offshore and shale projects, which generally have higher breakeven prices than other conventional fields. The pressure started in 2014 but bled into 2015 and 2016 which saw double digit decrease in capex in both offshore and shale spend.

Shale capex was able to rebound more quickly and began to again accelerate in 2017, but offshore still struggled with double digit declines in capex in 2017 and 2018. The subsea market, making up around 13% of the offshore oilfield services market, quite naturally followed the offshore market downturn. Operators spend on subsea equipment, SURF, and services went from $46 billion in 2014 to as low as $23 billion in 2018.

2019 is the year that growth in subsea capex will again pick up, with an expected 8% increase in 2020 compared to 2019. The subsea market will continue to plow forward in its robust upturn in the next five years, with capex growing 9% annually from 2019 to 2023, which should help drive total offshore oilfield services capex which is forecast to grow 6% annually in the same time frame.

Fueling the subsea market is an uptick in deepwater sanctioning. In the record year 2013, there was around $181 billion in sanctioned offshore greenfield investments. During the downturn this plummeted to around $43 billion in 2016, the lowest since the turn of the century. Since then offshore sanctioning has recharged, slowly in 2017 before 2018 brought us almost back to 2014 levels. 2019 sanctioning continued the momentum from 2018 with an increase of 43% to just above the $100 billion milestone.

This new wave of offshore sanctioning is not expected to come close to the record high greenfield sanctioning levels from the golden years between 2011 and 2013. However, interestingly for the subsea market, we have already reached close to the same levels as the average in the period 2011-2014 when it comes to deepwater (450 m/1,476 ft+) sanctioning. During the downturn operators favored scaled-down, phased and accelerated developments. Subsea tieback developments have been a preferred solution. Operators are expected to continue to sanction a high amount of subsea tieback projects in the years to come. This, together with a vast amount of floater projects already sanctioned and to be sanctioned, yields promising years to come for subsea suppliers.

In 2019, there was a big shift in subsea capex for projects in Norway and the UK, driven by major projects such as Johan Sverdrup as well as a vast amount of subsea tieback projects such as Fenja, Aerfugl, and Nova. 2019 also marks the starting point for what is expected to be a subsea wave in Brazil, with a 30% uptick in subsea capex compared to 2018. Going forward this trend is expected to continue, with subsea capex poised to increase around 14% annually from 2019 to 2023. This is particularly driven by increased capex for FPSO projects in the country. After a long investment hiatus during the downturn, Petrobras is now set to continue significant deepwater investments in 2020, building on an already strong year in 2019 when the operator awarded four FPSO contracts.

The awarded FPSOs are the giants Mero 2 and Buzios V with oil production capacity above 150,000 b/d and the medium-size FPSOs Marlim 1 and Marlim 2 for the revitalization project on the giant Marlim field. In 2020, Petrobras is expected to sanction five more FPSO projects (Integrado PQ, Itapu, SEAP, Mero 3, and Iara 2), making up as much as one-third of the global demand for FPSOs. These FPSO projects naturally come hand-in-hand with large subsea scopes.

Prior to the downturn, Petrobras was a giant driver for subsea equipment suppliers, doling out huge awards to major subsea equipment suppliers. In 2013, the operator awarded close to 200 subsea trees to three suppliers: Aker Solutions (80), TechnipFMC (49), and OneSubsea (59). In fact, subsea tree awards for Brazilian projects made up close to 40% of the global awards in 2013, a year in which more than 500 subsea trees were awarded. Subsea tree awards plummeted during the downturn eventually hitting a low of less than 100 subsea trees awarded in 2016. But just one year later, in step with offshore sanctioning, tree awards came in over twice as high and by 2018 awards were up to 300.

More deepwater sanctioning should drive subsea installations to deeper waters in the coming years. Comparing the installations in the previous cycle (2011-2015) with the ongoing cycle (2019-2023) a larger share of installations is expected in ultra-deepwater (1,500 m/4,921 ft+). This is largely driven by South America and the mentioned FPSO projects in Brazil, as well as ExxonMobil’s continued development of the Stabroek block offshore Guyana, but also accompanied by several projects in the US Gulf of Mexico as well as projects in Africa such as Aker Energy’s Pecan development offshore Ghana.

As subsea players took huge hits during the downturn, with yearly subsea revenues for the top eight suppliers falling from $34 billion in 2014 to $16 billion in 2018, measures were needed in order to improve efficiency. Subsea players were early when it comes to creating alliances, joint ventures as well as mergers and acquisitions. Three main players now dominate subsea equipment and subsea umibilicals, risers and flowlines (SURF) markets – TechnipFMC (merged company of FMC Technologies and Technip), Subsea Integration Alliance (alliance between OneSubsea and Subsea 7), and Baker Hughes/McDermott (alliance between the two). These players now can take on full subsea equipment scope and SURF scope for a project development, allowing the operator to award full subsea scope in one award, i.e. an integrated contract award. During the downturn this strategy was a necessity for the three main consortiums. Integrated contract awards were off to a slow start, with around $300 million in total awards in 2016 for Equinor’s Trestakk project awarded to TechnipFMC and Murphy’s Dalmatian North (for a multi-phase boosting system) awarded to Subsea Integration Alliance. 2017 and 2018 came in strong, with 12 integrated contracts awarded in 2017 valued around $3 billion, and nine integrated contracts in 2018 totaling around $3 billion. In 2019, this industry trend became the industry standard, with more than $7 billion in total integrated contract awards for as many as 17 projects. Recent integrated contract awards include giant projects such as Area 1 offshore Mozambique and Ichthys Phase 2 offshore Western Australia, as well as smaller projects like PowerNap in the Gulf of Mexico and Seagull in the UK North Sea.

With integrated contracts, suppliers have taken on larger risks by assuming more of the responsibility for delayed scope, and have not been compensated for that due to the squeezed market. However, there are clear efficiency gains achieved by this strategy, in everything from technology developments to organizational efficiency gains. These consortiums should now be in pole position for benefiting from the new wave of offshore projects. After benefiting from this approach during the last couple of years, by effectively pushing more of the risk over to subsea players, the question is if the operators pushed more of the pricing power over to these large consortiums, and now have to pay for it. •