Following several slow years in rig construction, things have only gotten worse over the last year and a half with the global pandemic and reduced demand. Fundamentally, the market remains oversupplied. Currently, a total of 61 rigs are under construction and jackups make up just over half of those units with 32. By comparison, the combined number of drillships, semis, and tenders currently being built totals 29, of which there are 18, 7, and 4 under construction, respectively. Out of these 61 rigs, only 7 were ordered with contracts in hand or by operators themselves, but four of those rigs are part of Sete Brasil and those original charters have long since been tossed out.

Keeping with the trend of the past few years, Chinese shipyards continue to have far more rigs under construction than yards in other countries. At the moment, a total of 28 rigs are being built in yards in China, 19 of which are jackups, while of the four tender rigs under construction globally, three are in China. Similarly, shipyards in Singapore are also focused on jackups, with 10 of the 16 units under construction there now being of that type.

South Korean shipyards are only working on drillships at the moment with all 10 rigs being built in the country currently being drillships, although that was the same number as last year as rig deliveries have also slowed to a crawl. Those 10 drillships in South Korea account for over half of the 18 drillships under construction worldwide, and 40% of all the floaters when you add in the seven semis being built globally. Speaking of deliveries, 14 rigs are slated to be delivered this year, with 30 more on the books for next year, and the last 17 scheduled for 2023. However, it should be noted that it is very unlikely that many of these rigs will be delivered as planned, particularly those scheduled for this year, as has been the case with deferred deliveries over the last few years.

Nearly all of the rigs currently being built were ordered speculatively, but very few have actually picked up a contract in the time since construction started. Of the 54 speculative units currently being built, a mere four have been awarded contracts since construction started: one semi in China and three drillships, two of which are in Singapore and the other is in South Korea. Petrobras awarded a contract to the semi, Sevan Developer, which is now owned by the shipyard and will be managed by SacAnb Offshore. This rig is technically a newbuild, but construction on the unit started in 2011 and has been on standby awaiting delivery at COSCO Shipyard in Qidong, China since 2014.

As for the drillships, one of them is Ocean Rig-ordered drillship Santorini, which is now owned by the shipyard Samsung Heavy Industries. While working in the US Gulf for Eni, the ultra-deepwater unit will be bareboat chartered to Saipem at a rate understood to be $40,000 per day with a purchase option of about $200 million. The other two drillships are both being built by Jurong Shipyard in Singapore for Transocean, and both will be going to the US Gulf for 20K projects. Deepwater Titan is scheduled to start its five-year charter with Chevron in the second half of 2022 when it will be working on the Anchor field. Meanwhile, Deepwater Atlas is expected to commence operations in 3Q 2022 with Beacon on the Shenandoah field, initially using dual BOPs rated to 15,000 psi for around 255 days. Then a 20,000-psi BOP will be installed over about two months, after which it will start the second phase of 275 days performing well completions.

As has been the case for years now, contractors and shipyards continue to put under-construction units on standby to wait out the industry’s prolonged downturn. At least 40 rigs that are somewhere in the process of being built are now on standby, and many of these units are ostensibly complete. Of those 40 units, 18 are jackups, 13 are drillships, and 4 are semis, as well as all four tenders that are being built. While not always officially on standby, every single rig currently being built has had its delivery pushed out, with the shortest delay being 10 months and the longest being around a decade. The aforementioned Sevan Developer will be delivered more than seven years after it was originally scheduled.

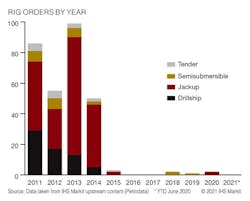

Already slowed to a crawl over the last few years, the number of new rig orders being placed remains next to nothing now, but that is to be expected from a market that now seems to be chronically oversupplied. Between 2015 and thus far into 2021, only eight rigs have been ordered. Zero orders were placed in either 2016 or 2017; followed by three orders over the next two years, all for semis; and again no orders so far this year. The two jackups ordered last year were for ARO Drilling, and these will be built collaboratively between Lamprell and International Maritime Industries. These are the first two of 20 jackups to be built for ARO Drilling, with the bulk of the remaining units to be built at a new shipyard in Ras Al-Khai, Saudi Arabia.

With such excess supply on the market, contractors continue to defer delivery on the rigs they have ordered. In some cases, the shipyards themselves have become the owner. To combat this development, shipyards have begun to engage in activities to which they are not normally suited, like marketing vessels. Keppel, for example, is not just actively engaging buyers to offload rigs, but is open to doing bareboat charters, stating that it has put together a team to lead these efforts as the “skill sets required are somewhat different from what we do traditionally at the shipyard.”

Meanwhile, Valaris has made an arrangement with Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering that frees the contractor from buying the two drillships being built at the yard. However, some opportunities are available to sell new rigs, such as with India’s ONGC, which is looking to purchase six newbuild jackups, including ones on standby at yards around the globe. Additionally, another avenue has emerged to find work for stranded newbuilds, and that is the energy transition to renewable energy. Converting rigs to production or accommodation units isn’t new, but at least seven rigs so far – four jackups and three tenders – have already been or are in the process of being transitioned to windmill installation vessels, all at yards in China.

As noted, the worldwide pandemic has also contributed to construction delays, most notably at Chinese shipyards. For example, Sembcorp Marine recently explained that since the onset of COVID-19, a majority of the yard’s projects have been delayed by at least 12 months; and the re-introduction of measures to mitigate the spread in early 2021, like tighter border control, have disrupted supply chains and exacerbated the shortage of skilled manpower.

Meanwhile, Keppel announced earlier this year that it plans to exit the offshore rig building business after completing the units still under construction. The company will be restructured into three parts, separating construction and ownership of legacy drilling rig assets from its core operations, while focusing on the energy transition to better align with its sustainability goals. Similarly, Lamprell also indicated that it will be remaking itself to focus more on the energy transition, but it will not leave the rig-building game. Since Keppel’s announcement, Sembcorp Marine and Keppel have inked a memorandum of understanding on a potential combination of their shipyard businesses. The move aims to pivot the companies towards the energy transition, including offshore renewables, but Keppel’s legacy rigs would be omitted from the combined entity.

Then there is the ongoing saga of Sete Brasil and its newbuild ultra-deepwater floaters. While in negotiations, Sete notified Petrobras that it would not be able to comply with some conditions stipulated in the deal by the required deadline, which had already been delayed twice to January 31, 2021. However, the contractor also requested the start of new negotiations. On this point, Petrobras explained: “Faced with this scenario and in search of a joint solution, considering that the agreement will not produce the expected effects, Petrobras’s Executive Board authorized the beginning of a new negotiation with Sete Brasil.”

The original, now-defunct agreement between the two companies was made back in March 2018. Through that deal, Petrobras was to charter four of Sete’s rigs for 10 years each with a rate of $299,000/day. Critical to this was Sete’s need to sell the four uncompleted newbuild rigs to a joint venture between Magni Partners, Mubadala Investment Company (MIC), and Etesco. Under the plan, Magni and MIC would own the rigs through a new drilling contractor named Knarr Drilling, while Etesco would manage the drilling service contracts, before the two sides were to be later combined. The rigs involved were semis Urca and Frade, which are being built by Keppel, and drillships Arpoador and Guarapari, which are being built by Jurong.