Jeremy Beckman - Editor, Europe

The revival of exploration off northern Cuba has rekindled interest in the Bahamas. Although no wells have been drilled off the islands since 1986, new geological studies suggest strong analogies among producing provinces from Cuba and southern Florida to giant fields such as Cantarell in the southern Gulf of Mexico.

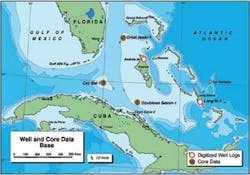

Spearheading the review is BPC, formed in 2005 by Alan Burns, who also pioneered deepwater exploration off Mauritania with his previous company, Hardman Resources. BPC is the only company active offshore the Bahamas, operating four contiguous licenses on the median line with northeast Cuba, and the Miami license between Grand Bahama Island and the Florida coast. The combined acreage covers an area of 15,676 sq km (6,053 sq mi).

Over the past three years BPC has compiled a detailed inventory of the islands’ exploration history based on all available data, including 7,000 km (4,350 mi) of seismic lines, well cores, and rock samples dating back to the 1950s. Using contemporary imaging techniques, it has identified 22 leads in its five offshore licenses, with potential for large traps containing structures of up to 500 MMboe.

The company has an office in the Bahamian capital, Nassau, with two full-time staff and a legal team on retainer. “As a very small, start-up operation,” says COO Paul Crevello, “we had to demonstrate to the government our ability to perform both technically and financially before securing our licenses.”

Crevello, a geologist recruited by Burns in 2006, is based in Boulder, Colorado. His area of expertise is carbonate reef systems, notably the structural setting formed in and around the Bahamas that he began investigating as a student at the University of Miami in the 1970s. This play was also the focus of major oil companies including Gulf Oil, Shell, and Standard Oil during the islands’ first post-war exploration phase. All were looking for the same type of carbonate reservoirs that had been proven onshore in the Middle East.

In 1978, Crevello joined Marathon, which at the time had interests in large carbonate fields such as Yeats onshore Texas and others in the UAE and Libya. Crevello directed the company’s global carbonate geological exploration research, also running a carbonates training program which included organizing field trips to the Bahamas, Belize, and southern Florida for coral reef studies. When the research facility in Denver closed in 1994, Crevello moved to the Far East to start another training program at the University of Brunei, funded by Shell, and later his own consultancy, Petrex Asia, in Kuala Lumpur.

Drilling history

Previous exploration around the Bahamas occurred in phases between 1946 and 1987, all in shallow water. The first well, drilled in 1947 on Andros Island to a subsurface depth of 14,583 ft (4,445 m), was abandoned with no significant well shows. From 1948-55, Gulf Oil led the way, conducting the first experimental underwater seismic and gravity surveys in this area. During this period, Gulf also drilled the 826-Y well off Key West, Florida – the sole oil discovery to date in the region – which flowed 18 bbl of 22-24º API crude from an anhydrite/carbonate interval below 10,000 ft (3,048 m).

In 1958, Zapata, owned by Howard Hughes and George Bush Sr, undertook an ambitious program (at the time) which led to drilling of Cay Sal No.1, offshore north-central Cuba. This location was drilled jointly by Chevron and Gulf a year later, the well encountering “live” oil shows from 12,682 ft (3,865 m) downwards.

From 1959-68, these two companies continued to drive exploratory activity, conducting various unproductive marine seismic programs which included the use of dynamite as an energy source. In 1970 they joined forces with Mobil to drill the Long Island and Great Isaac Bank wells: the latter, in BPC’s Miami license, flowed gas and condensate to the surface from the 16,900-17,700 ft (5,151-5,395 m) interval.

Over the following decade, the focus switched to digitally based seismic, gravity, and magnetic surveys. Further seismic and core samples also were acquired as part of a scientific project to analyze the Bahamian carbonate bank. Thereafter, various oil companies commissioned seismic, geotechnical, and geochemical studies.

The final well was drilled by Tenneco in 1986 on the Doubloon Saxon structure in BPC’s Donaldson license. This was also the deepest well drilled to date, at 21,470 ft (6,544 m) TD, encountering live oil shows over a thick interval. Post-drilling, both Tenneco and Shell acquired more experimental surveys, but they and the remaining operators quit in 1988 when the licenses expired, due to a combination of high costs and low oil prices.

More recently, Kerr-McGee and Liberty Oil & Refining applied for exploration licenses north of Grand Bahama Island. Western Geco acquired speculative seismic in this area, well away from BPC’s licenses, but otherwise activity around the Bahamas ground to a halt.

Cuba parallels

BPC began its quest for all the available geological and well data in 2005, purchasing materials from oil companies, universities and research institutes. These included storage facilities in northern Britain, and cores stacked on shelves at a university warehouse in Louisiana. “We took paper copies of all existing data sheets, digitized them, and put them in our workstations,” Crevello explains.

The subsequent review using modern interpretive techniques found that most of the wells drilled around the Bahamas were either in the wrong locations or were hampered by poor quality seismic or imaging constraints. “Both the Long Island and Great Isaac wells were drilled blindly,” Crevello suggests, “while Gulf in 1960 found a stratigraphic trap off Key West that produced 15 bbl of 22-24º API oil on test, but could not delineate the oil column. And in those days the drilling technology was not available to test the potentially larger structures held by Tenneco out at 500 m (152 m) water depth.”

However, based on analysis of oil shows of varying quality, widespread reservoirs and seals, and hydrocarbon saturations from log interpretation – particularly in pre-Cretaceous unconformity sections – BPC believes active petroleum systems could be present.

“We also drew on literature on source rocks in Cuba published by institutes in Spain and France,” Crevello adds, “which revealed shales with a high organic material content – up to 14%. We feel the same rocks could be present in the sub-surface in our southern licenses.

“This area is just north of the productive North Cuba field and thrust belt, which was created when the Caribbean plate collided with the southern margin of the North Atlantic plate. The same age source rocks extend farther west along a compressed fault belt into the southern Gulf of Mexico: the analogues are mainly with the multi-billion barrel fields such as Canterell and Golden Lane/Poza Rica in the Mexican sector, rather than the smaller deepwater fields on the US side which are located on a passive, subsiding margin.

“One problem with the northwest Cuba area is that it lacks a good seal, possibly due to its paleogeographic position during the early Cretaceous. But we are dealing here with big carbonate platform reservoirs and evaporate sealing beds. Carbonate reservoirs provide the main source of Cuba’s prospective resources, which the US Geological Survey estimates at 18 Bbbl recoverable, while the Cuban Petroleum Company puts reserves at more than 20 Bbbl.”

Negotiations

In recent years, the Bahamas has stayed off the industry’s radar, Crevello believes, because it is too close to the US for groups working in the Caribbean, where the focus has been on Trinidad and Venezuela. Lack of serviceable well data has been another issue, as was the previously unfavorable Bahamian tax regime. Now, however, the exploration terms are more generous, with licenses renewable every three years for a period of up to 12 years.

BPC is pursuing multiple farm-outs in its various licenses to fund the next phases of exploration.

“We’ve been talking to majors,” Crevello says, “and they see upside potential for huge fields on our acreage. Although today’s economic environment is weaker, we will continue to search aggressively for suitable partners.

“Our initial focus will be on seismic acquisition in deeper water, where we have identified numerous structures, and on establishing petrophysical parameters. We will also look at commissioning a satellite-based hydrocarbon seep study. Then, using our old data, we will gear up for organic-geochemical studies for source potential analysis, followed by additional petrographic calibration of well logs. This program could take 18 months to complete.

“If negotiations with farm-ins go well, we would contemplate starting seismic acquisition later this year – in this region, the best time would actually be the hurricane season, as that’s when the weather is most stable versus winter, when many fronts pass through the area.”

As for drilling, which could get under way in 2012, BPC would expect its share of costs to be borne by the farm-in operator. Any commercial discoveries would likely be developed via a floating production system (in deeper water) or a jack-up platform. Nearby export infrastructure includes a 20 MMbbl oil storage terminal at Freeport, owned by PDVSA.

In the event of a major gas find, the export options could be a low-cost compressed natural gas tanker, offloading perhaps to the proposed Port Dolphin submerged LNG reception terminal offshore Florida; or a pipeline taking the gas subsea either to Fort Lauderdale (from fields in the Miami license) or to Freeport.