Analysis: A delayed energy transition could make or break the upstream sector

Oil & Gas Journal Breakfast Series:

Energy Transition

As the risk of a “delayed energy transition scenario” increases, so does the possibility of a much greater pull on future oil and gas supply, says global consulting firm Wood Mackenzie.

The firm defines “delayed transition scenario” as a five-year delay to global decarbonization efforts due to “ongoing geopolitical barriers, reduced policy support for new technologies and cost headwinds.”

But meeting this future hydrocarbon demand would require a significant increase in upstream investment, resulting in higher hydrocarbon prices and significant shifts in corporate strategy, according to Wood Mackenzie’s latest Horizons report.

According to the report “Taking the strain: how upstream could meet the demands of a delayed energy transition,” a variety of external pressures have weakened government and corporate resolve to spend the estimated US $3.5 trillion required to restructure energy systems to limit both hydrocarbon demand and global warming.

Wood Mackenzie’s latest Horizons report focuses on the additional resources and spend required if the upstream sector was to meet higher-for-longer oil and gas demand, and the resultant consequences.

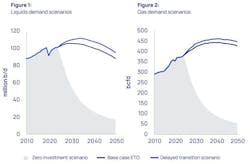

Under this scenario, the world would require 5% more oil and gas supply and 30% higher annual upstream capital investment. Liquids demand would average 6 million b/d (6%) higher than Wood Mackenzie’s base case to 2050, and gas demand would average 15 bcfd (3%) higher than the base case.

“Meeting rising demand in the near term in either the delayed scenario or the base case poses little challenge to the sector; plenty of supply is available,” said Fraser McKay, head of upstream analysis for Wood Mackenzie.

“However, stronger-for-longer demand growth is a much stiffer ask. A five-year transition delay would require incremental volumes equivalent to a new US Permian basin for oil and a Haynesville Shale or Australia for gas,” said Angus Rodger, head of upstream analysis for Asia-Pacific and the Middle-East.

Increased upstream investment

While we believe the global oil and gas sector could meet this demand through existing resources and future exploration, significant investment would be required to achieve it.

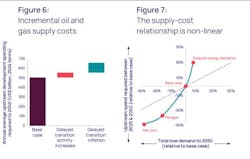

Wood Mackenzie estimates that upstream spending would have to rise by 30%, resulting in US $659 billion of annual development spend versus US $507 billion in the base case, and US $17 trillion versus US $13 trillion in total to 2050 (all in 2024 terms).

“We have calculated the sector’s cost elasticity by integrating our field-by-field annual supply models with our global supply-chain analysis,” said McKay. “This includes an assumption for continued operational efficiency improvements, which the industry could very well outperform, mitigating some of the inflationary impact.”

But increasing spend will not be easy, even if the signs of increased demand are present. More activity would put significant pressure on the supply chain – parts of which are already running near capacity – and project costs would inflate.

“The industry’s current strict capital discipline edict would also have to change or, at least, what defines discipline would have to evolve,” said Rodger.

“Corporate planning prices would increase if the outlook for the market improved, with increased confidence in demand longevity. In that environment, higher development unit costs and breakevens would likely be tolerable,” said McKay.

Price escalation

With the higher cost of supply, so too would come higher prices for both oil and gas. Wood Mackenzie’s Oil Supply Model forecasts a Brent price rising to over US $100/bbl during the 2030s in a delayed transition scenario. It falls towards US $90/bbl by 2050, averaging around US $20/bbl higher than our base case over the period (all in 2024 terms).