Catarina Podevyn

Dr. Roger Knight

Wei Liu

Infield Systems Ltd.

As one of the two emerging giant economies in modern day Asia, India is placing the fulfillment of its dream of “greater wealth for all” on continuing economic growth fueled by cheap energy. However, the lukewarm response of international companies to the country’s offshore prospects, evidenced by Petrobras’ recent stated intension of leaving its stake in block KG-DWN-98/2 where significant finds have already been made, means that, effectively, only India’s own domestic company Reliance Industries currently is producing deepwater hydrocarbons off the nation’s coasts.

The global gas market at a glance

Despite the coldest winter in Britain for 31 years and China in 40 years, and while the spot price of oil has increased considerably from the low of $30/bbl during January 2009 to around the $80/bbl mark at the time of writing, gas prices have remained at a relatively stable $4-$5/MMbtu – less than half the 2008 high. The world is faced with a looming gas surplus. This is due to the combination of unexpectedly rapid development of unconventional gas sources, sluggish global demand, and an increase in alternative energies. The forecast for future gas prices remains flat around the current level or is expected to experience only a marginal increase over the next two years. Over 2010, realized volatility data suggest a 9% monthly volatility or 30% whole-year volatility. Over the short term (2010-2011), ISL forecasts this to result in a fluctuation in gas prices within a range of $4.3 - $6.5/MMbtu.

Asia’s rising energy demand

As parts of the global economy recover from the worst recession to hit some countries in 70 years, oil and gas markets are forecast to grow at a slow to moderate rate over the medium term. Gas demand will require at least another two years before 2008 levels of consumption are re-established. With energy security emerging as a key theme in global macroeconomic policy, the US is expected to make a major effort towards substantially reducing its gas imports, while demand growth from both the European and African regions is forecast to remain relatively flat in the medium term. The changing dynamic of energy demand forecasts is, however, expected to be predominately driven by the ever rising demand from Asia’s continually growing economies, particularly those of India and China.

In this light, both Chinese and Indian NOCs, and Indian IOCs such as Reliance, seek to establish themselves within the global hydrocarbon market, investing in E&P activities across Asia and Africa, and looking to expand operations within the Latin America markets to gain access to energy supplies.

Simultaneously, with rapid industrial expansion over recent years, national government moves to introduce greater transparency, and liberal pricing mechanisms within the industry, a greater number of foreign companies, both super-majors and independents, have entered operations within Asia’s offshore sector.

Indeed, the region itself offers abundant support for offshore development, including a large skilled and cost-effective labor force and the presence of many high-capacity fabrication yards. While significant challenges remain within the region, particularly the diverse nature of fields and challenging environmental conditions, Asia as a whole and, as will be examined in greater detail, particularly India, will become a key region for oil and gas production over the forthcoming decade.

The Indian situation

Dating to the 1970s with operations commencing on ONGC’s Mumbai High field, India’s hydrocarbon industry has been characterized by a high level of regulation, bureaucracy, and state dominance. Now with a decade of rapid economic growth behind it, the country’s rising energy consumption has hit record levels, with present energy growth projected to increase at a rate of 8% a year through to 2032.

In order to maintain this pace, $150 billion in industry investment will be demanded. This will be expected to translate into a supply increase of up to four time’s current levels over the next 20 years. As a result of such rising energy demands, India’s import bill has increased to unprecedented levels, with total crude oil imports rising from $12.9 billion in the 2000-2001 period to $77 billion in 2008-2009. This has caused rising concerns as to the future of energy security, which now comes second only to food security in terms of government priorities.

However, with rapid economic growth and an increasing hunger for energy supplies, India’s government increasingly has tried to encourage private and foreign investment into its hydrocarbon industry. With two-thirds of its sedimentary basins remaining unexplored, recent years have witnessed increased efforts to liberalize the oil and gas sector in order to make it more attractive to the outside world.

While a large proportion of future energy supply growth is expected to come from the nation’s coal industry, there also is increased interest in India’s deepwater natural gas reserves. This brings into play the Krishna-Godavari basin. This area is in the western part of the Bay of Bengal and covers more than 24,000 sq km (9,266 sq mi) offshore in water depths up to 2,000 m (6,562 ft). The highest profile discovery to date is Reliance Industries’ D6 in 2002, holding up to an estimated 14 tcf of gas.

Since then the area has witnessed record exploration activity by the national oil company and Indian independents, with discoveries of up to 20 tcf of gas being reported in 2005 by Gujarat State Petroleum Corp., a further 20 tcf in the D-3 and D-9 blocks by Reliance Industries in May 2009, and 10 tcf by ONGC in June 2009. As such, the Krishna-Godavari basin has been billed as one of the key exploration areas of natural gas in the world going forward.

Therefore, with much of the country’s currently producing fields facing declining production levels, the K-G area has been hailed as the North Sea of India’s struggling oil and gas industry.

India deepwater production to 2014

As detailed in Infield’s latestDeep and Ultra-deepwater Market Update 2010-2014, the development of India’s fields are expected to form the major proportion of Asia’s deepwater growth over the forthcoming five years, with Asia itself expected to be the fastest growing region in terms of fields d ue onstream, increasing from five fields during 2005-2009 to 40 newly producing fields by the end of 2014. While not associated traditionally with deepwater developments, the development of deepwater prospects offshore Asia will be explored with increasing intensity to try to satisfy the region’s energy demands. As seen in the figure below taken from Infield’s Deepwater Market Update 2010-2014, India is expected to dominate the Asian region in terms of fields coming onstream within the forthcoming five-year period, and most of those from the Krishna-Godavari basin.

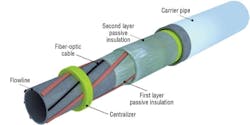

The success of Reliance in the KG-D6 block is presented as one of the foremost accomplishments of India’s fledging deepwater industry, and highlights what is possible when governments, private enterprise, and global engineering expertise integrate effectively. Using the experience of key contractors and deepwater engineering specialists across Asia, the US, Europe, and the Middle East, the KG-D6 project has surpassed several industry records, having been brought in a record of six years from discovery to onstream. This compares to an industry average of nine to 10 years for similar deepwater facilities.

With the success of D6, Reliance is looking to further develop the area. It already has a total of 36 discoveries in the KG-D6 block. The D-1 and D-3 discoveries starting up in April 2009, target ultimate production of 80 MMcm/d (2.8 tcf/d), twice India’s current national gas production. Certainly there is vast scope for the development of the Krishna-Godavari basin over the next decade.

At present, Reliance looks to tie-in eight additional discoveries near the D-1 and D-3 fields, and the remaining identified prospects are estimated to hold potential hydrocarbons of 39 tcf of gas and 1.6 Bbbl of oil.

At this crucial point in time, when IOCs look to re-assess balance sheets and E&P strategies following the global economic recession, India’s deepwater potential cannot be overlooked. Simultaneously, it is vital for India’s government and oil companies to continue to work alongside global players to develop discoveries to their full potential and to maintain pace with the nation’s projected economic growth and resulting increase in energy demand.

The establishment of the New Exploration Licensing Policy (NELP) in 1999, launched by the India to encourage greater international investment, predominately by introducing Production Sharing Agreements to accelerate the pace of exploration, it appeared that India soon would become a key oil and gas industry market. Although NELP rounds over the previous decade brought over $10 billion in investment commitments, last year’s NELP VIII was a disconcerting disappointment. Only half of the 70 oil and gas blocks on offer received any interest, and even India’s own Reliance Industries failed to place a bid.

While it may be tempting to blame the economic downturn, which unquestionably affected E&P investment decisions across the globe, in reality the Indian situation is far more complex.

Contrary to the government’s aim for greater international involvement, 2010 has seen a mixed response towards India’s deepwater developments. While the first quarter of the year has seen key developments such as the beginning of operations of Transocean’s drillshipDhrubhai Deepwater KG2 under Reliance, recent months have also arguably affected IOC confidence in India’s emerging deepwater market, with Statoil and Petrobras backing out of an appraisal drilling campaign in the deepwater KG DWN-98/2 block following concerns over reserve potential. However, Shell and BP reportedly have interest in filling the withdrawers’ places, with a possible FLNG solution to be proposed.

In addition, and although the NELP licensing rounds and increased economic liberalization have made significant headway toward rectifying the high level of regulation and bureaucracy associated with India’s hydrocarbon industry, substantial obstacles remain. Oil companies typically wait at least a year before final approval of exploration licenses or development programs, for instance. In a world of continued uncertainty and energy price volatility, operators may see this as a wait that cannot be accommodated. As a result of the poor response to NELP VIII and the faltering international interest within India’s oil and gas blocks, the Indian government has responded by offering far fewer blocks as part of NELP IX, expected to occur in the second half of this year, in order to increase competition. After that, an Open Acreage Licensing Policy (OALP) is expected to be adopted to attract greater interest from key super-majors such as ExxonMobil and Chevron.

Outside supplies

With demand expected to significantly outstrip supply in the years ahead, the NOCs are working to ensure as much of the country’s energy supply is produced domestically as possible to keep increases in energy imports to a minimum. While Reliance works alongside partner BG to expand production at the Tapti, Panna, and Mukti fields, ONGC works to increase its recovery rate at the Mumbai High structure.

Despite this, and with concerns about the validity of reserve estimates in the KG block KG-98/2, operators now seek to expand outside the nation’s hydrocarbon territories. ONGC reportedly wants to borrow up to $10 billion over the next decade to keep pace with rival Chinese and South Korean bidders in the international market. By 2025 the Indian state operator targets an annual production of some 60 million metric tons (66 million tons) of oil and gas to be derived from overseas assets, almost twice the level of India’s current output of 34 million metric tons (37 million tons).

Furthermore, while increased investment into the country’s energy sector is a central focus of government policy, the rising energy demand and a sustained high rate of economic growth predicted over the forthcoming 20 years make increased imports inevitable. Just last month, Saudi Arabia agreed to increase crude supplies from 25.5 to 40 million metric tons (28 to 44 million tons), while India looks to add 1 MMb/d to its refinery capacity over the next two years to process those additional Saudi imports.

With India predicted to remain one of the fastest growing economies in the world and current GDP growth standing at 6% CAGR between 1995 and 2009, the IEO has forecast a doubling of energy consumption by 2030 to over 5 MMboe/d. Even with the Indian government’s continued efforts to increase international investment and the introduction of the OALP starting in 2011, a substantial increase in India’s import bill is inevitable. While on the one hand this raises significant concerns over future energy security, and an increasing dependence on the Middle East in particular, at the same time India is increasing its ability to exert influence upon energy exporting countries, and will inevitably feature as a key energy market, from both an upstream and downstream perspective going forward.