Roger Knight, George Venturas - Infield Systems Ltd.

Guns have dominated the headlines in Nigeria.

The common sentiment from commentators across the board on the nations of Africa’s Atlantic basin margin is that they collectively face a very bright offshore future. The only caveat - and it is a big one in most states - is that the bright future will only be accessible if the region is able to get its domestic policies right and maintain law and order.

Infield examines the upcoming FPSO and LNG developments in the region, focusing especially on Nigeria, and takes a closer look at the issues that are shaping future developments in the area for operators.

Nigeria

In Nigeria this year, there has been a visible increase in militant activity in the Niger River States. The election of the thirteenth president of Nigeria, Umaru Musa Yar’Adua, in April did little to calm the violence in the region. Yar’Adua is also the Minister for Energy, and his family’s fortune is inextricably linked to Nigeria’s downstream assets.

The security situation in the Niger Delta continues to be a concern for companies operating in the region. Exploration is inhibited, and production numbers tend to fluctuate with the attacks. The increase in abductions has made it unlikely that Nigeria will meet its target of establishing 40 Bbbl of crude reserves by 2010.

Militancy has even hindered operators pursuing remote fields. TheAkpo, Agbami, Bosi, and Usan FPSO projects are all some distance from shore, but some of the future developments as far as 100 km (62 mi) from the Nigerian coastline still are not considered entirely safe.

Despite Nigeria’s having the world’s seventh largest natural gas reserves, it flares much of its gas as if it were a waste product. Legislation outlawing gas flaring is changing this. An example is the deadline of April 2007 given to Shell as a point at which the company was expected to end flaring.

The increase in gas production is part of the reason for the large number of onshore gas liquefaction facilities expected to be built in Nigeria. A troubling fact about these facilities, however, is that they will be built in areas where insurgency activities have intensified over the last 18 months.

Like Nigeria, Angola is no stranger to unrest and violence. The country suffered significant destruction during a 27-year civil war, and much of its limited onshore infrastructure is still in ruins. Revenue from offshore oil is crucial to Angola’s stability and critical for its future.

Fortunately, the news from Angola and the outlook for the country are considerably brighter than for Nigeria.

Total’s Rosa field in block 17 has just come onstream to beef up Girassol’s declining production profile, adding to the increasing volumes being pumped from the neighboring Dalia field, which came onstream in Dec. 2006. Production from block 17, coupled with large recent production increments in Chevron’s block 14 and Exxon Mobil’s Kizomba block 15, led to Angola becoming the newest member of OPEC early this year.

Future FPSOs in Nigeria

Most of the production offshore Nigeria comes from FPSOs.

Total’sAkpo and Chevron’s Agbami FPSOs, both in deepwater, will come onstream on schedule in 2008. Akpo represents 28% of the future Nigeria FPSO spend, while Agbami accounts for 27%.

TheAgbami FPSO will have a daily production capacity of 250,000 barrels of oil, and 450 MMcf of gas and will have the ability to inject 450,000 barrels water to improve reservoir flow and prolong production. The FPSO, which will be operated by Chevron affiliate Star Deep Water Petroleum Ltd., is under construction at the Daewoo yard in Korea. When the vessel is onsite, it will tap reserves that will eventually total over 1 Bboe in greater than 5,000 ft (1,524 m) water depth.

TheAkpo FPSO, under construction at Hyundai, will produce reserves in OML 130 that are reportedly as high as 600 MMbbl of light oil and condensates and 4 tcf of gas.

Other near-term FPSOs for Nigeria include Peak Petroleum Nigeria Ltd. and Equator Exploration’s troubled shallow-waterBilabri. The Bilabri FPSO was to be deployed later this year, but trouble with the vessels owner has resulted in the contract being terminated.

Capital expenditure relating to future Nigerian FPSO projects.

Production from another shallow-water FPSO,Okoro Setu in 21 m (69 ft) of water, appears likely to happen sometime next year.

Exxon Mobil’sBosi FPSO, which was expected to be deployed in 2011, is facing severe bottlenecks. And Shell is unlikely to begin production from Bonga South West in 2010. Rumblings from Shell indicate the project could be shelved.

Even with the delays and setbacks, though, there are several FPSO projects and onshore LNG facilities that will emerge in the next four years.

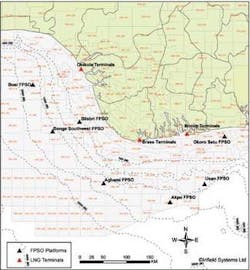

Using Infield’s EnergyGateway, a new online mapping service with a front-end to the Infield Offshore Energy Database, it appears that Nigeria will see some progress on LNG projects before year-end.

Later this year, we expect the sixth Bonny Island LNG train to be completed. A seventh train is to be added in 2011.

The Olokola LNG Terminal (trains one and two) has been delayed and will not be operational until at least 2012.

The Brass LNG terminal, estimated to cost as much as $8 billion, is expected to be operational in 2012.

Other FPSOs

Outside Nigeria, there are other FPSO concerns. On Angola block 15, a fifth vessel for Kizomba D has been put on the back burner, with ExxonMobil preferring a tieback to existing block 15 facilities rather than deploying another FPSO.

Future Nigeria FPSOs and LNG terminals. Source: Infield EnergyGateway

On the positive side, the region has seen some significant discoveries, such as Anadarko and Tullow’s Mahogany and Hyedua in Ghana.

Another significant deepwater find was Total’s Mer Tres Profonde Sud block off Congo (Brazzaville). There also has been continuing activity off Equatorial Guinea where gas/condensate finds are adding to the potential feedstock for more trains at the recently commissioned Bioko Island LNG plant.

On the downside, low production levels at Woodside’s Chinguetti field off Mauritania may lead to the eventual withdrawal of that operator from that country if remedial work and infill drilling cannot boost flow rates.