The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) gave rise to a wide range of new rights and obligations in international law. In particular, the Convention conferred on maritime states a new range of rights in relation to their continental shelves and the right to claim an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) which, unless compressed by geographical considerations or the rights of neighboring states, extends 200 nautical miles offshore.

So far as EEZs are concerned the Convention has led not only to a large number of bilateral and multilateral maritime boundary negotiations between states, but also to a considerable body of state practice and case law. A great deal of the work of EEZ delimitation is quite technical in nature, but the subject has major political, economic, and administrative implications. States that have established EEZs are entitled to a wide range of rights connected with exploration and exploitation of the economic resources of the zone.

Oil is valuable, and even a small oil field can make a substantial difference to the economic life of the citizens of the coastal state to which the EEZ belongs. Because so much can be at stake, maritime boundary disputes in relation to areas thought likely to be rich in oil can and do lead to serious international tensions - sometimes to military hostilities.

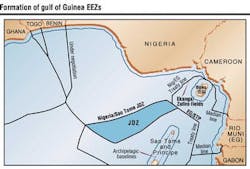

The waters of the Gulf of Guinea are rich in hydrocarbons. With a population well in excess of 100 million and a lengthy coastline, Nigeria is the largest and most influential state in the Gulf. In recent years, under the leadership of President Obasanjo, his Minister of State, Hon. Dubem Onyia and Alhaji Dahiru Bobbo, Director-General of the National Boundary Commission, Nigeria has made impressive strides in resolving land and maritime boundary issues with almost all its neighbors, a process which is almost invariably beneficial to both sides.

Nigeria has also played an important part in the creation of the Gulf of Guinea Commission, which can be expected to play an influential part in the coming years in promoting international development and cooperation in the region.

In almost all cases, Nigeria's progress on its international boundaries has been made through the active pursuit of friendly bilateral negotiations with its neighbors, particularly Benin, Niger, Equatorial Guinea (whose capital, Malabo, is situated on the island of Bioko - the former Fernando Po) and the archipelagic state of São Tomé e Príncipe.

Relationships have been significantly difficult with only one of Nigeria's neighbors, Cameroon, where disputes on a range of issues have now been referred to the International Court of Justice in the Hague for its decision.

Joint Development Zone

When Nigeria came to negotiate a detailed maritime boundary with São Tomé e Príncipe (STP) it was established that the two sides had widely different ideas about the appropriate position of the dividing line between their respective EEZs. STP claimed archipelagic status under UNCLOS, and put forward a huge EEZ claim, which overlapped the claimed EEZs of all its neighbors.

The relevant Articles of UNCLOS provide for an equitable solution to the delimitation of both the continental shelf and the EEZ. The only guidelines given in the Convention to states faced with these problems is to refer them to the Article in the Statute of the International Court of Justice, which sets out the applicable sources of international law. This leaves substantial room for the parties to argue about what is appropriate according to the particular facts of any given case.

With so much room for dispute, the initial negotiations can easily lead to deadlock, neither government being willing to be seen to give way to a foreign state on an issue of potentially vital significance to the protection of the national patrimony. Such a deadlock can lead to the sterilization of economic development until resolved, which can take years, or even decades.

To their considerable credit, the two governments decided that they could do better than that. Building - paradoxically - on an agreement to disagree, they signed a treaty identifying a zone of disputed ocean territory in respect of which both sides' respective EEZ and continental shelf claims would be fully maintained. They would develop jointly, benefiting in the proportions spelled out in the treaty itself.

The two sides had to agree not only on the proportionate benefits that each would obtain, but on the role of a Joint Ministerial Council and a Joint Authority to govern the zone, on regimes for the exploration and development of hydrocarbon and other resources, for taxation, security, environmental protection, health and safety issues.

Unlocking development

A great deal of work has been necessary in order to structure and document these matters in a manner acceptable to both sides. But the prize is a great one, namely the unlocking of economic development in a valuable part of the maritime space claimed by the two states.

There have been a number of Joint Development Zones in other parts of the world, prompted by a range of political and economic imperatives, but the Nigeria/São Tomé e Príncipe Joint Development Zone is the first in the Gulf of Guinea, and has been designed in such a way as to take particular account of the needs and practices of the two states and the geographic and economic realities of the life of the region. It is an impressive achievement.

When Nigeria and Equatorial Guinea came to delimit their common maritime boundary, they were able, after several years of negotiation, to agree a single maritime boundary, but were left with the problem of what to do about oil fields that straddled the boundary.

Cross-boundary unitization

The agreed boundary left the Ekanga oilfield on the Nigerian side of the line, and the larger Zafiro oilfield that was already in production on the Equatorial Guinean side. Nigeria stipulated that there must be an agreement, that the two oilfields, which form a single structure straddling the new boundary, be exploited jointly for the benefit of both states and their oil concessionaires in pre-agreed proportions.

There are numerous precedents for cross-border unitization of straddling oil deposits, notably in the North Sea. Each case, however, is different, and much will depend on the type of joint exploitation contemplated, the structures of the economic ventures participating in it, and the overall wishes of governments.

In the present case, negotiations are now well advanced for the unitization of the deposits on a mutually satisfactory basis. These negotiations, as is only to be expected, have sometimes been quite difficult, but both sides have a considerable incentive to agree, namely the possibility of implementing the wider treaty.

Conclusion

Some two hundred international maritime boundaries remain to be delimited in various parts of the world. From the South China Sea to the North Atlantic, the implications for resources and for regional politics can be profound.

There is, however, a growing body of techniques and expertise available for managing any disputes which may arise, without the very considerable delays and expense attendant either on protracted deadlock or on international litigation.

In the short and the longer term, the interests of the oil industry lie with certainty, and with the resolution or at least effective management of inter-state disputes that may prevent economic activity, or discourage necessary long-term investment. As drilling becomes economically viable in ever greater depths of water, the number of areas where potential inter-state rivalry can lead to excessive uncertainty and risk likewise has the potential to become larger.

This is particularly so in areas where UNCLOS gives states the possibility of extending the limits of their continental shelves. In some cases, major international oil companies will be more experienced than their host governments in assessing the problems that may result and suggesting solutions and have an important part to play, alongside governments, in enabling economic activity to continue in areas where the boundaries are uncertain, or give rise to technical difficulties.

Author

Alan Perry is a Partner in the Public International Law Group of D J Freeman (Solicitors), located in London.