Jim Redden

Contributing Editor

While it may be antipathetic to the sensibilities of a drilling or production engineer, planning for eventual decommissioning early in the construction of a subsea well could save a wealth of money and potential headaches when the time comes.

The Helix multi-serviceQ4000 on location in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico.

Clearly, the plugging and abandonment (P&A) of decommissioned wells represents no financial upside, other than the possible recycling of the subsea tree. Consequently, reducing costs and avoiding future environmental liability are the prerequisites for successful subsea decommissioning. Those responsible for abandoning wells say planning for termination at the time wells are being conceived, along with the wholesale adoption of rigless abandonment technologies, would go a long way to lessen the economic pain when the end arrives.

“Decommissioning is nothing but a big hole on your books. It’s an entry and nine times out of 10 when you go out to do a decommissioning, it’s going to cost more than you have on your books. If you can do your P&A and decommissioning for less than what is on your books, it actually comes back as income,” says Wes Spincic, vice president of well operations and intervention for InterAct PMTI, an Acteon company. “So, it’s possible you could make money with a decommissioning.”

From all indications, that hole Spincic referenced is expected to deepen appreciably in the not-too-distant future. While it is difficult to get a firm handle on how many subsea wells will have to be discontinued in the near term, what is clear is that as industry reduces the number of surface facilities, subsea production will take an ever-larger role.

$30 billion market looming

Estimates suggest there are more than 3,800 flowing subsea wells around the world. One 2007 study predicted that between 2000 and 2011 upwards of 4,100 new subsea wells are expected to be drilled and completed worldwide. At some point, those wells will reach the end of their productive life. Kurt Hurzeler, commercial manager for Helix Well Ops US, says his best guess has around 400 subsea wells due for decommissioning in the Gulf of Mexico alone over the next four to five years. An InterAct-authored study for Oil & Gas UK earlier this year forecast 910 subsea and 3,725 platform wells will have to be decommissioned in the UK sector, many over the next 15 years.

While the lion’s share of the subsea decommissioning market is in the mature North Sea and GoM, executives say Southeast Asia, Brazil, and even West Africa are emerging as potentially fertile grounds for abandonment equipment and services.

“Many of the West Africa nations are trying to get on the green side, so they are looking more at decommissioning wells in some of their maturing fields. Southeast Asia will be a big market for decommissioning, but I think it will be slow to develop and not as quick as everyone wants it to be,” says InterAct’s Spincic.

In the GoM, the US Minerals Management Service (MMS) strictly governs the abandonment of wells, including requiring they be plugged permanently one year after production ceases. Operators also must post bonds to ensure they meet all their regulatory obligations. Today, some $556 million of the $1.2 billion in total supplemental bonds operators posted in the GoM goes toward making certain they meet their decommissioning responsibilities. The UK and other offshore sectors look to pattern their requirements after many of those the MMS enforces.

”The MMS regulations are considered the benchmark for abandonment throughout the world,” says Jerry Gilmore, vice president of operations for Proserv Offshore, which the MMS commissioned three months ago to prepare a study of the technical issues and methods to decommission in more than 9,842 ft (3,000 m) of water.

The potential global market for subsea abandonment equipment and services has been estimated as high as $30 billion. In the InterAct study, the UK trade association reported the potential market for abandonment services could exceed $15 billion in the North Sea alone. Clearly, abandonment companies say, operators need to take a hard look at what can be done at the onset to help ease the financial burden down the road.

Simplicity will help reduce P&A costs

“The biggest thing they can do is to stay away from complexity and keep it simple. Keep in mind that you have to unscrew this thing (tree) once you put it on the seafloor. Other things they can do, for example, are to take care of external casing pressure as they go and address them at the time,” says Gilmore.

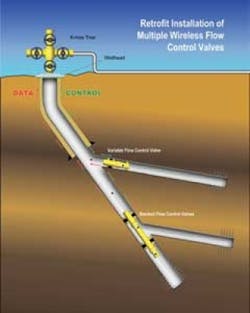

As many subsea producers are outside the depth limitations for divers, those seafloor installations typically are performed with ROVs. The key, abandonment companies maintain, is designing the subsea system to facilitate ROV seabed installation.

“If you design everything so that an ROV puts it together, you have a much better chance of using that ROV to take it apart. If you design it to be put together on the surface and then submerged, it becomes really difficult to take it apart,” Gilmore says.

Spincic agrees, saying, “Everything has to be ROV friendly, because that’s your lifeline. In fact, an ROV forces simplification with no oddball casing sizes and all that.”

Owing to the enormous sums that are and will be spent on decommissioning subsea wells, operators now are looking closer at steps they can do ahead of time to reduce their costs. That mindset is diametrically opposite the once-prevalent attitude among operators to focus on drilling and producing a well as quickly and efficiently a possible

Rigless abandonment successfully recovered the wellhead during the Elang-Kakatua decommissioning.

“With the huge dollars involved, the higher level of technology and the educated work force we have today, people are putting more thought into abandonments,” says Gilmore. “We have so many more intricate tools and designs today.”

Others say steps that can be taken during well construction include setting the production packer below the top of the cement in the casing. The packer also should be far enough below to provide the space sufficient for the cement plugs needed to eventually seal the well. Abandonment companies warn that setting the packer too high during drilling increases costs and risks during decommissioning as remedial cement otherwise would be required behind the production casing.

In addition, all permeable zones above the production casing shoe should be sealed with cement. Generally, it is easier and faster to circulate cement behind the casing string during drilling than it is during decommissioning when the production tubing is in place.

Although it may appear simplistic on the surface, documenting cement volume and annular seals while drilling and any other measurements that would require testing during a P&A would reduce the cost of decommissioning. According to abandonment companies, documentation of all pertinent well data also helps ensure that any problem cropping up during the process can be remediated quickly and effectively. Trying to find those records when the well stops producing can be daunting, since many offshore assets have changed owners a number of times.

Rigless technology advancing

Many of the intricate tools and other technologies Gilmore aluded to have been developed for rigless abandonment using dedicated, dynamically positioned (DP) diving and similar support vessels. Replacing the high costs and availability issues of conventional rig-based abandonments with rigless technology is a cost-effective alternate. In the first rigless abandonment ever undertaken off Australia, Helix said the client saved up to 30% compared to what would have been incurred with a rig. While rigless technology has gained wider acceptance in the GoM in recent years, it still is not embraced wholly.

“I don’t think it’s a market that’s been explored as much as it should be,” says Chuck Purdy, well engineering manager for Pro- serv Abandonment Services. “There’s been a tremendous advancement in (rigless) technologies, but it hasn’t yet gained the true industry acceptance of rig abandonments.”

Spincic says, however, the times appear to be a changing. “With the subsea market improving, the interest in rigless (abandonment) has increased quite a bit over the past two years. Rigless abandonment is the key, and I think that’s where we have to go.”

Ironically, a host of technologies like heave-compensated cranes for DP vessels were developed in response to hurricanes Rita, Katrina, and Ike. “The hurricanes really have been a learning tool and a lot of the expertise and equipment developed as a result is starting to spill over into subsea well abandonments,” says Proserv Project Solutions Manager Esaú Velázquez.

The Helix Energy Solutions Group is an industry pioneer in designing technologies for rigless intervention and abandonment. The flagship multi-service HelixQ4000 MODU, stationed in the GoM, is designed to operate in up to 10,000 ft (3,048 m) water depth. More recently, the company introduced its Well Enhancer light weight subsea well intervention vessel. Complementing the fleet are newly engineered tools and systems, including a subsea lubricator, a specialized cutting tool capable of severing multi-casing wellheads in a single pass, and an onboard deployment technology that creates an over-stern moon pool work area or deploys over an existing moon pool.

The company’s new subsea top drive and many of its other technologies were employed in tandem for the first ever rigless subsea well abandonment in Southeast Asia. The rigless and riserless abandonment was in 328 ft (100 m) of water at the decommissioned Elang-Kakatua field in Australia’s Timor Sea.

A Proserv crew cuts casing during an offshore decommissioning.

InterAct, primarily through its Claxton Engineering Services, WellCut Decommissioning Services, and InterMoor have developed a range of rigless technologies, including the recently introduced subsea lubricator and a single-well abandonment tool. The same with Proserv, which has been involved directly in decommissioning for more than 20 years and over that time has developed a portfolio of rigless tools, including cold cutting and friction stud welding.

With the advancements of recent years, most people involved with subsea decommissioning say technological issues are not the problem. Rather, it is universal operator acceptance of rigless technology, which, in turn, would translate to more investment in building up of a limited fleet. In April, TSMarine unveiled a strategy to spread the costs of subsea abandonments among more than one operator, thereby making best use of the available fleet of suitable DP vessels. Today, the company is employing that approach in the North Sea.

“Technology is not the limiting factor. We can design and manufacture tools to work in deepwater. We can deploy them to the seafloor and even find them with the right telemetry tools, but the time and effectiveness of the operation may not be satisfactory. Part of the selection process is down to commerciality,” says Helix’s Hurzeler.

While subsea and platform well decommissioning may not be one of the first things operators think about when they drill a prospect, it is something that will never vanish. Jules Schoenmakers of Shell Exploration and Production Europe drove that point home in a presentation at the Oil & Gas UK Southern North Sea Decommissioning Conference early this summer.

“The GoM holds 46,000 wells, of which 21,000 have been abandoned. For every abandoned well there are two new wells drilled.”