Offshore carbon capture storage: a forecast of transatlantic collaboration

The European impetus to reduce and contain emissions has led to a number of different collaborative business partnerships in the UK and European marketplace. Over the past year, these partnerships that can capture carbon (particularly CO2) gave gained momentum to store CO2 into offshore storage wells and basins.

The logic and momentum of these proposals is now making its way into the American marketplace, and this trend is expected to continue. It is quite likely that we will see the emergence of several US-UK partnerships along the way.

Geopolitically, the concept of offshore carbon capture and storage (OCCS) has received support from the United Nations, the organizing body of the 2015 Paris Agreement. The OCCS concept is particularly favored since it (in contrast to renewable energy) proposes to actually removing carbon (CO2) from industrial sites, and sequester it into geological reservoirs.

To date, the primary example of this type of UK-US partnership is the Storegga Geotechnologies (Storegga) joint venture with Talos Energy. In June, the two companies announced that they would pursue an OCCS project in the US Gulf. Talos Energy is a leading oil producer in the US Gulf, while UK-based Storegga is separately spearheading Scotland’s Acorn project. That project has the backing of Shell (Netherlands), and ExxonMobil (US) recently joined Acorn as well. So here again we can see the tie-ins between US and UK corporate entities in the OCCS marketplace.

Apart from the Acorn project, there are additional OCCS projects that are being collaboratively developed in the United Kingdom. These projects include several of Europe’s leading offshore oil producers, namely bp, Eni, Equinor, Shell, and TotalEnergies. Interestingly, these companies all have operating experience and producing assets in the US Gulf of Mexico, but they have not to date leveraged the offshore Europe OCCS impetus into the GoM. However, given the logic of these North Sea projects, it seems likely that events will unfold in a similar fashion in the US Gulf of Mexico. Both regions are mature oil-producing areas with significant offshore assets. When one examines the numbers of producers and developers that operate in both regions, the prospects for collaboration on OCCS projects becomes quite compelling.

Repurposing offshore infrastructure

Importantly, the Storegga-led Acorn project holds the distinction of receiving the first-ever OCCS storage license; it was granted by the UK’s Oil and Gas Authority in 2018. But Storegga’s ambitions (via Pale Blue Dot Energy) can be traced back to 2013. As such, Acorn’s first mover advantage can bolster Talos Energy’s efforts to pursue OCCS projects in the US Gulf. “Storegga is a recognized leader in the rapidly-evolving [OCCS] space,” said Talos Energy CEO Tim Duncan at the time of the deal. The Acorn project also has Harbour Energy as an equal partner. Harbour is said to be the largest listed independent oil and gas producer in the UK North Sea. Formed through Chrysaor’s acquisition of Premier Oil last October, Harbour owns and operates a significant amount of offshore infrastructure.

Additionally, the US-based Gulf Offshore Research Institute (GORI) is actively working to repurpose GoM platforms for OCCS projects. This initiative includes collaboration from members of industry, government agencies and regulatory bodies, academic institutions, and technology companies and specialists (Full disclosure: Hernandez Analytica is also involved in this endeavor). The GORI and the Acorn projects are similar, as both endeavors are focused on repurposing offshore infrastructure for OCCS developments.

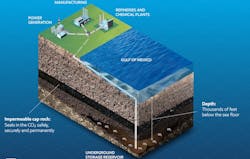

Apart from these efforts, ExxonMobil has also announced its intention to undertake offshore carbon storage in the US Gulf. According to one report, the oil and gas supermajor wants to sequester up to 100 million metric tons of CO2 per year “under Gulf of Mexico waters.” The project aims to capture CO2 from the 50 largest industrial emitters along the Houston Ship Channel, and pipe it to offshore reservoirs up to 6,000 feet below the sea floor. ExxonMobil has estimated that the offshore carbon sequestration market could be valued at $2 trillion by 2040.

Project feasibility

There are those who doubt the feasibility of large-scale offshore carbon sequestration. But the feasibility of OCCS has been proven and realized off the Norwegian coast by Equinor, first at Sleipner (1996) and later at Snøhvit (2008). At the Sleipner offshore complex, millions of tons of CO2 (removed from produced gas) are sequestered at sea. At Snøhvit, an 88-mile subsea pipeline connects an LNG plant (industrial emission source) to an offshore reservoir at Snøhvit. This successful example is crucial, since Storegga, ExxonMobil and others will almost certainly follow the Snøhvit piped approach.

Transatlantic collaboration

There are additional UK projects which have been awarded sequestration licenses for OCCS, apart from the Acorn project. One of these is the Northern Endurance Partnership (NEP) project off the eastern coast of England, an effort spearheaded by bp. The goal of the NEP project is to merge emissions from two separate industrial sources (hubs) via subsea pipelines into a single export pipeline, and from there into subsea sequestration. Besides bp, the NEP also has the backing of Eni, Equinor, Shell, TotalEnergies – all of which have assets in the US Gulf. At some point, one or more of these European companies can be expected to leverage its offshore sequestration experience, learned in the North Sea, into the US Gulf of Mexico.

The Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University recently commented that: “In many ways, [Net Zero Teesside] is like Houston. It contains the UK’s largest chemical and refining cluster and with it the largest associated [CO2] emissions.” Of course, the US Gulf Coast oil infrastructure stretches far beyond Houston, a calculus that raises emissions in the region. Talos Energy estimates those emissions to be 1,000,000 tons of CO2 per year, and that metric is likely to be a key driver for OCCS development in the US Gulf of Mexico.

The US Gulf of Mexico is America’s second leading oil-producing region, on a year-over-year basis. And its ability to outpace other regions is linked to its history of advancing new offshore technologies. These technologies can be leveraged for future OCCS projects, or to execute workovers on existing wells for sequestration purposes. This in turn will present an alternative to plugging and abandoning old wells, by converting them into CO2 injection sources; while simultaneously prolonging the utilization of older platforms for OCCS purposes.

OCCS momentum

With OCCS projects gaining critical momentum in the North Sea, the logic of this market need will inevitably gain impetus in the US Gulf of Mexico. Transatlantic relationships can grow and be fostered. We see this already in the Talos/Storegga project. In the US, further discussions are under way between the oil industry, government, and academia that can lead to additional such projects in the US Gulf. To be sure, potential sequestration projects in the US Gulf are likely to require tax credits such as those that can be found in section 45Q of the IRS tax code. We may be on the cusp of seeing a new market segment emerge, one that merits watching closely in the coming years.