Northwest Europe assesses feasibility of hydrogen marketplace

Hydrogen has both enormous potential but also an uncertain future. Even though the sector is in its infancy, the global pipeline of more than 200 large-scale hydrogen projects is worth more than $300 billion – equivalent to three-fifths of 2019 upstream spending. However, the debate on hydrogen’s potential differs in each region of the world – reflecting the different decarbonization challenges and economic development opportunities they face.

The goal here is to review the status of the hydrogen market in Northwest European countries; unpack the barriers to the growth of the industry; and discuss the factors that will influence the future role or ‘business case’ for hydrogen in Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and the UK.

Northwest European context

The Northwest region is leading the deployment of hydrogen (and associated CCUS) projects in Europe. The current pipeline of projects around the North Sea reflects the will of governments and existing energy market leaders to protect relevant value chains, such as that of natural gas, while exploring the opportunities of renewable power beyond electrification.

While this has resulted in an increasing support for the upstream (producing) side of the value chain, when it comes to hydrogen, downstream sectors play an equally important if not more significant role in the overall business case.

Renewable energy producers and oil and gas companies are among the key stakeholders in taking the leadership to integrate stakeholders across the value chain. However, while these synergies and collaborations have resulted in an initial pipeline of conceptual projects, only those with a strong facilitator have managed to move the most ambitious projects from concept to FID.

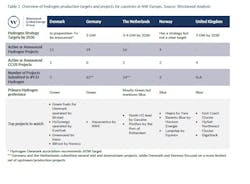

Hydrogen strategies and targets

Broad support for the hydrogen economy in Northwest Europe is reflected in the EU and UK hydrogen strategies that primarily focus on the supply side of this emerging market. The EU’s preference is in electrolysis-based technologies (green hydrogen), while the UK strategy (initially) favors the production of blue hydrogen derived from natural gas with carbon capture technology.

In addition to these strategies, 22 EU member states and Norway launched the Important Projects of Common European Interest on hydrogen (IPCEI hydrogen) in late 2020 to support the development of the whole value chain of clean hydrogen in Europe. Similarly, the UK has been supporting the decarbonization efforts of key sectors through different mechanisms, such as the Industrial Decarbonization Challenge and the CCUS Cluster Sequencing Process. Access to public and private finance is also much improved across the value chain, partly to help de-risk the earlier stages of projects.

The result has been the emergence of national hydrogen strategies and roadmaps – typically with a 2030 timeframe. Years of research and knowledge-building from demonstration and pilot stages have now been translated into conceptual plans for large‑scale hydrogen production hubs, valleys and corridors.

The question countries and companies across the value chain are now asking is how to ‘tap into’ the opportunity. In Northwest Europe we are seeing a diverse set of stakeholders from the natural gas and renewable energy value chains, ports, industrial hubs and other interested parties, all trying to make sense of this opportunity – resulting in an equally diverse set of (proposed) projects.

Managing risk and complexity

Despite the broad support and a strong project pipeline, sizable barriers exist in turning this vision into reality. While the current state of the hydrogen economy could be compared to the early stages of the development of renewable power, the hydrogen value chain is in fact significantly more complex. There are multiple stakeholders and regulatory officials that must be satisfied; technical and commercial hurdles; and safety concerns to address and overcome.

The biggest hurdle to overcome is the current high cost of both green and blue hydrogen. That high cost prevents hydrogen from being an automatic economic alternative. In addition, regulatory uncertainty around the standards for ‘low carbon’ hydrogen tends to undermine even the most important blue hydrogen-based projects.

Governments have been working to fill policy gaps and provide confidence to involved investors and stakeholders. These efforts have included harmonized standards, and proposed financial subsidies for the scaleup of electrolyzers. But to manage this risk, the key theme that emerges in all projects is ‘collaboration’ among stakeholders, and the search for synergies across the value chain to overcome the barriers that limit the deployment of blue and green hydrogen to the current and future demand sectors.

Route to commercialization

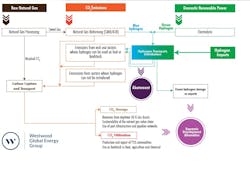

The complexity of the hydrogen question is partly driven by the multiple potential uses of hydrogen in a country, and the infrastructure that exists within a country to deliver that hydrogen.’ This will in turn depend upon the presence of an existing natural gas value chain, the availability of renewable power, as well as the sources and sinks for CO2.

The strategic objective of a hydrogen project should be either to support a country in meeting its domestic climate commitments or stimulating economic development (e.g. exports).

The key challenge then is in selecting the right commercialization route for each country. While cost is a consideration and strategic support by a country is essential, three influencing factors have been identified to making a business case for hydrogen a reality:

1. Matching the opportunity of hydrogen with a country’s needs

2. Identifying synergies and collaboration opportunities

3. Determining a business case facilitator.

Acknowledging these influencing factors can help in the initial design of a project and move projects from concept to FID. Each of these three factors is examined below.

Matching the opportunity

The versatility of the hydrogen molecule allows for its potential application in a wide range of sectors, including steelmaking, chemical processes, refining, and a broad spectrum of Power-to-X (P2X) commodities (typically used as feedstock for the food processing, chemical and chemical industries). Heating in homes and transport are also much-discussed applications. Its versatility and possible outsized impact in supporting the decarbonization of our economies has been hailed as a ‘game-changer’ for the road to net-zero.

The challenge to hydrogen is whether it is the appropriate decarbonization solution; and if so, where its use should be prioritized. Consideration needs to be given to the following:

Structural barriers. Some ‘hard to abate’ sectors would require a too significant structural change to make hydrogen a technically and/or commercially feasible option. In the steel sector for instance, to create a sizable (and economic) enough demand for hydrogen in their operations, European producers will likely have to abandon their Blast Furnaces and move to a Direct Reduced Iron (followed by Electric Arc Furnace) process.

Alternatives. End-use markets are currently weighing up the various alternatives available to decarbonize their operations, whether it be electrification, hydrogen, CCS etc. The final ‘choice’ is not set in stone and will evolve. For example, The Athos CCS project in the Netherland was cancelled after the project partner Tata Steel opted for Direct Reduced Iron route (with hydrogen as a reducing agent) to decarbonize its operations.

Demand. Hydrogen markets face a chicken and egg dilemma. While countries like Denmark and Norway have the potential to produce hydrogen, the lack of clarity on its ultimate end-use potentially holds back the necessary investment in renewable (or natural gas) energy sources needed to support hydrogen development. Imports can offer a solution, but again, clarity on the end-use market is important to warrant this. On the other hand, end use markets will not develop until hydrogen is viewed as an attractive alternative.

Synergies and collaboration opportunities

Once the appropriate target end-use sectors have been selected and there is more clarity in the downstream part of the value chain, projects leaders (typically on the supply side) can determine which other stakeholders need to be involved and build synergies through collaboration. Aligning the stakeholders strengthens the business case.

For example, Denmark identified the transport sector as its main target for decarbonization and therefore engaged with the biomass and waste-to-energy value chains, from where captured CO2 can be sourced and a P2X industry created (particularly in synthetic fuels). Projects are further engaging with district heating opportunities to generate additional revenues from residual heat. P2X exports can also provide an economic alternative for the excess hydrogen the country can produce.

In the UK, synergies are being created between key emitters (e.g. heavy industry, the power sector) and the oil & gas sector. This takes advantage of the availability of depleted oil and gas fields in the North Sea close to industrial sites (or ‘clusters’) for the generation of blue hydrogen and the storage of CO2.

Business case facilitator

The initial effort of project leaders and governments looking to develop an opportunity for hydrogen requires a further element: a business case facilitator. Denmark offers a good example of this. The close collaboration of industry associations Wind Denmark and Brintbranchen (Hydrogen Denmark) – together known as the P2X Alliance – has provided a consistent and aligned voice for stakeholders in hydrogen and P2X. This has been essential in framing a business case for hydrogen in a country with low domestic demand, but with vast resources and the need to seek for economic alternatives to its oil and gas business. Several P2X projects owe their progress to this alliance.

Essentially a business case facilitator helps align a particular proposal/project with the government strategy to address its domestic emissions or create a new economic development opportunity. However, the facilitator also allows for a quicker and more focused identification of policy gaps in the value chain of a project. As a result, governments can develop financial and regulatory mechanism that meet the actual needs of a hydrogen or hydrogen/CCUS proposal aiming to effectively decarbonize prioritized sectors.

Conclusions

There is broad support for both blue and green hydrogen in Northwest Europe – backed-up by regional and country strategies and targets, as well as a strong pipeline of proposed projects. Each country has its own unique context, objectives and approach in decarbonizing its economy. Consideration needs to be given to all parts of the value chain to be able to fully understand what role hydrogen can play and how it can be commercialized.

The complexity associated with developing hydrogen projects can be managed by matching the opportunity of hydrogen with a country’s needs; identifying synergies and collaboration opportunities across the value chain; and crucially, determining a business case facilitator. These actions will help create policy alignment and will help promote the development of country/project-specific support mechanisms.

The authors

David Linden is the Head of Energy Transition at Westwood Global Energy Group and is responsible for defining and implementing the group’s Energy Transition strategy. He has 15 years’ commercial experience across the global energy value chain. Linden has held key commercial and regulatory roles at Corus, BP, Mott MacDonald, and Wood Mackenzie. Latterly he was a Director in Wood Mackenzie’s Energy Transition consulting division, growing the power, renewables, EV and emerging technology sectors.

Ricardo Grandas-Vargas is a Research Analyst at Westwood Energy. He covers hydrogen, CCUS and other energy transition topics, particularly for the Northwest Europe region. His background is in chemical engineering, and he has just finished an MSc. Climate Change Management and Finance at Imperial College. Ricardo has gained experience in process system engineering and advanced oxidations processes from his education and work experiences in Abu Dhabi, Brazil, and Colombia.