North Sea E&P trends: moderate or better upswing expected

Editor's note: This feature first appeared in the July/August 2024 issue of Offshore magazine.

By Mathias Schioldborg, Rystad Energy

Norway and the UK – as the two largest oil and gas producing countries in Europe – have seen their respective upstream sectors take somewhat diverging paths during the last decade. While Norway’s investments and production levels have recovered well from the downturn observed around the COVID-19 pandemic, the maturity of the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) has prohibited growth for its upstream sector – although a near-term sanctioning upswing is set to spark new activity in its waters. An examination of the key upstream trends observed in the two countries is presented below covering investments, production, sanctioning, and exploration.

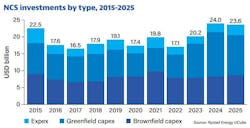

The Norwegian Continental Shelf (NCS) is currently seeing a strong upswing in spending, with an impressive $24 billion projected to be invested this year. This marks 19% growth from the $20.2 billion seen last year and a whopping 40% from the $17.1 billion spent in 2022.

The elevated expenditure comes in the wake of Norway’s temporary fiscal regime, introduced in mid-2020 to stimulate activity amid the pandemic, as companies are now building out a considerable portfolio of new ventures – such as Aker BP’s $11.8-billion Yggdrasil hub and its $5.3 billion Valhall-Fenris development. The regime offers tax relief on greenfield capex for all projects that had their plans of development and operation (PDO) delivered between June 2020 and the end of 2022. As a consequence, the NCS is currently undergoing a strong greenfield cycle.

The current spending level on the NCS is projected to hold up well in the short term, and total investments are projected to clock in at $23.6 billion next year, driven by continued high greenfield spending, a small increase in brownfield campaigns, and a noticeable increase in exploration expenditure. When the current greenfield cycle concludes towards 2030, investments are expected to moderately cool down.

Oil and gas production on the NCS has recovered well from the drop seen in 2019 and the initial phase of the pandemic. Total production last year hit 4.05 million barrels of oil equivalent per day (boe/d) – spread almost equally between liquids and gas – marking an impressive 9% growth from the 3.7 million boe/d produced throughout 2019.

Oil and gas production is currently undergoing a growth cycle, and total output is expected to increase to 4.08 million boe/d this year and 4.14 million boe/d next year. A driving force behind this expected rise is Equinor’s Johan Sverdrup field producing at plateau, but new projects such as Equinor’s Johan Castberg FPSO vessel starting up by the end of this year will also contribute. A vast portfolio of subsea tiebacks sanctioned under Norway’s tax relief scheme also bolster the near-term outlook, such as Aker BP’s Kobra East/Gekko, OKEA’s Hasselmus and ConocoPhillips’ Tommeliten Alpha.

In Rystad Energy’s base case, production on the NCS to is projected to hold up well in the medium term and range around 4 million boe/d towards 2030. This is, however, reliant on projects currently under development performing as outlined in their PDOs – particularly Johan Castberg and the Yggdrasil hub – as well as discoveries being sanctioned in the near term. Some key discoveries set for sanctioning soon include Equinor’s Ringvei West and Peon in 2025, which hold roughly 360 million and 170 million boe in estimated recoverable volumes, respectively.

After 2030, Norway’s oil and gas output is expected to slowly start decreasing, as major hubs such as Troll, Oseberg, and Snorre initiate their decline phases. Given Norway’s vast undiscovered oil and gas resources, however, a share of this envisioned longer-term decline may be offset by new discoveries, and the actual decline rate will be highly sensitive to how European demand develops and future policies set by Norway’s government.

During the last decade, the UKCS has seen a more subdued development for its oil and gas industry. This has largely been driven by the maturity of the region as newer projects have been unable to offset natural decline from mature hubs, as well as a downturn in spending during the pandemic. Frequent changes in the fiscal regime have also impacted companies’ willingness to invest on the shelf.

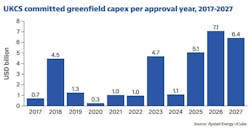

A moderate upswing in sanctioning activity is, however, projected in the near term. Following a dip to $1.1 billion this year, committed greenfield spending is set to rise to an impressive $5.1 billion next year, $7.1 billion in 2026 and $6.4 billion in 2027 – marking a substantial increase to the trend observed during the last decade.

Two key ventures potentially lifting next year’s outlook are Ithaca Energy’s Cambio floater project and NEO Energy’s redevelopment of the Buchan area, projected to facilitate greenfield investments of $2.1 billion and $1.1 billion, respectively. In 2026, BP’s $2-billion development of the Clair South field stands out as the largest project, but several smaller-scale subsea templates also contribute strongly, while 2027 will likely see projects such as Orcadian Energy’s Pilot FPSO ($1.6 billion) being sanctioned. Medium-term sanctioning levels on the UKCS could, however, be altered by potential changes in policy following the country’s elections in July this year.

As companies seek to secure their longer-term growth potential, a small upswing in exploration activity on the NCS is currently evident. From last year’s 28 drilled exploration wells, an increase to 40 is projected this year, although this figure is subject to changes and delays near the turn of the year. This year’s wells are split between 22 in the North Sea, 10 in the Norwegian Sea and eight in the Barents Sea. Next year, 27 wells are currently planned, but more drilling campaigns will likely be planned in the meantime.

Revived exploration interest in Norway’s Arctic waters comes after Gassco – Norway’s state-owned operator of most pipeline infrastructure – suggested that building a new gas export pipeline could potentially be profitable. The area holds the largest volume of estimated technically recoverable, undiscovered gas resources on the NCS, but has previously been beset by disappointing wildcat results and currently has a lack of available gas processing capacity. This has, again, put a damper on companies’ willingness to explore there in the last few years. Eight wells this year, therefore, marks a notable increase in overall interest in the area, which again could help unlock some of the vast remaining resource potential it holds. Additionally, there was a growth in the number of awarded licenses in the Barents Sea under Norway’s latest licensing round (APA 2023) – again underlining elevated interest for the region.

Increased exploration activity in the North Sea also strengthens this year’s outlook, particularly driven by infrastructure-lex exploration (ILX) campaigns around larger hubs such as Troll, Balder and the yet-to-start Yggdrasil hub, which is being developed with additional slots for nearby discoveries. This comes as operators aim to quickly extract nearby reservoirs by tying them back to existing infrastructure, which typically lowers the unit development costs of projects and shortens the buildout time. Given the level of infrastructure in the North Sea, there is likely to be continued high ILX activity in the area towards the turn of the decade.

The Norwegian Sea is set for a normal year in terms of exploration activity, with its 10 wells fitting with the trend observed during the last decade. This year’s efforts will mostly comprise ILX ventures around the Heidrun, Skarv, Aasgard and Aasta Hansteen hubs, but also a frontier well in the north-eastern Norwegian Sea.