Offshore staff

LONDON – Gas demand is rising in Asia while at the same production is falling, according to Wood Mackenzie.

This will lead to an increased reliance on LNG imports, greater price risk and reduced security of supply. Upstream output could drop substantially unless governments in the region act to incentivize both IOCs and NOCs to develop Asia’s remaining gas resources, warned WoodMac’s Asia-Pacific director, Angus Rodger.

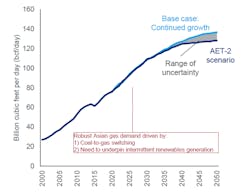

The consultant expects gas demand on the continent to rise steadily through 2050, peaking at just below 140 bcf/d.

Demand will be driven by a switch from coal to gas. And although renewable energy in the region is growing rapidly, the reliability of gas as a back-up is still needed to ensure the stability of the grid.

Although Asia has substantial gas resources, it lacks commercially attractive opportunities, Rodger said. Around 61 Bboe is onstream with a further 56 Bboe discovered but deemed non-commercial.

Over 70% of the resources is stranded gas, due to a high level of contaminants, remote locations and/or demanding fiscal terms.

Only China at present is increasing gas output. Production in South Asia has been in decline since 2010, and the same has applied to South East Asia from 2015.

And the upstream outlook is not positive, with many pre-FID projects across Asia (25 tcf in total) struggling to progress, and capex investments and exploration activity also falling.

On average, around 430 exploration or appraisal wells per year were drilled during 2000-2015, but the total now is averaging below 100 wells/year, excluding China.

Upstream capital spend across Asia could fall by 50% over the next five years if the current pre-FID projects do not move forward, Rodger warned.

This could lead to dependency on imports across Southeast Asia reaching 83% by 2035, with the attendant security of supply and price volatility risks.

So, governments should consider incentives to lift activity and help develop native resources.

Output is in fact rising at various gas fields in the region due to higher prices and post-pandemic demand. However, at many fields operators have either postponed or canceled development and regular maintenance programs and this could lead to more equipment failures, unplanned outages, and faster production declines.

Many of the largest gas fields that supply markets in Brunei, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand are entering their fourth decade of production, and if their declines are faster than expected, this could worsen the supply gap.

Examples include Myanmar’s aging and rapidly depleting Yetagun and Yadana offshore fields, both of which export gas to neighbor Thailand. And Woodside canceled Myanmar’s sole pre-FID project, the 2-tcf Block A6 offshore development, following the military coup.

These developments will likely inflict a 300 MMcf/d shortfall of imported gas on Thailand, speeding up the country’s dependency on imported LNG, which could hit 100% by 2038 based on current commercial reserves, Rodger claimed.

So, governments in the region should re-examine their oil and gas fiscal structure, he advised.

In previous up-cycles upstream spending would have risen, but IOCs have fewer priority projects now in the region and are prioritizing other basins elsewhere in the world.

11/29/2021