Alex Chakhmakhchev

Peter Rushworth

IHS

A paucity of new giant discoveries in mature onshore petroleum provinces and restricted access to new business opportunities in major oil and gas producing countries are pushing the industry to explore offshore locations and especially frontier deepwater and ultra deepwater basins. IHS data indicates that, in the last 10 years, more than half of new global oil and gas reserves were discovered offshore. Deepwater and ultra deepwater discoveries are becoming the dominant source of new reserve additions, accounting for 41% of total new reserves based on a statistical evaluation of discoveries between 2005 and 2009. Despite all recent challenges such as the global economic downturn, credit crises, fluctuation of oil prices, and increased capital costs; this trend will likely continue, making offshore and particularly deepwater, key contributors to new supply growth.

The analysis presented in this paper is based on the IHS international E&P databases and the IHS Global E&P Reporting Service. There are many definitions frequently used for dividing and analyzing trends by water depth. In this paper, we used the following definitions: shallow water (SW) <= 400 m (1,312 ft), 400 m < deepwater (DW) <= 1,500 m (4,921 ft), and ultra deepwater (UDW) > 1,500 m; all related to bathymetric depth.

Phases of offshore development and licensing activityAlthough the first offshore well may have occurred as early as the late 1890s, by and large, significant offshore activity was not forthcoming until after World War II. From inspection of available, contracted areas, it is possible to delineate phases of offshore exploration. At present, nearly all countries with coastlines have an offering for offshore exploration. Some exceptions exist such as the withholding of offshore positions of both the western and northeastern US. However, the opening of Federal areas off the southeastern US coast and eastern portion of the Gulf of Mexico in late March 2010 should increase potential exploration areas. In addition, a number of countries are negotiating with respect to drilling and exploration activity in the arctic region.

Despite limited technology and infrastructure, the first phase of offshore exploration continued from the 1940s to 1982. The year 1982, was a peak year for new field discoveries. In the 10 years prior to 1982, the number of offshore fields discovered per year more than doubled to 198. The pace and number of offshore fields increased rapidly in the latter part of this first phase of offshore development. Some significant finds of this era expanded regions of the Persian Gulf, the Bombay High, and identified the giant fields in the North Sea. Smaller, but equally significant finds were made in China and Australia.

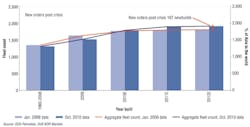

The second phase of offshore development may be viewed as the time period from 1983 to 2005. During this time, the number of new fields fluctuated dramatically from a low of 116 new offshore fields in the years 1993 and 1994, to the largest number of offshore fields discovered in the year 1990 (192 discoveries), never reaching the previous high noted in 1982. This span of time is notable for a large increase in inventory of offshore contract area as the number of countries offering acreage spiked from 95 in 1985 to 133 in the year 2005. There was an increase of valid contract area inventory from about 5.5 million sq km (2.1 million sq mi) in 1995 to 9.2 million sq km (3.6 million sq mi) in 2005. In 1985, the number of contracts for offshore acreage was about 2,300. In 2005, at the end of Phase Two, just over 12 years later, the number of contracts exceeded 8,500.

During this second phase, Brazil found traction with deepwater fields such as Albacore Leste and Roncador. West Africa, the North Sea, the Caspian region, and Australasia all noted significant contributions in new offshore discoveries.

While it may be premature to call a trend short of the historical data providing an unambiguous definition, it seems likely that a third phase of offshore exploration is underway. Nearly all countries with offshore offerings are in play. However, the larger available area for consideration in exploration does not transform non-optimal geological terrains into prime areas for elephant-hunting. Similarly, the risk environment for a poor or marginal situation onshore does not necessarily make a similar offshore target of that same country a better opportunity. The basis for careful analysis, surveys, geologic, and engineering evaluation rises with increasing risk and potential for reward, or failure.

Phase Three of offshore development represents an increase in offered acreage mainly due to the increase in new deepwater and ultra deepwater areas. At the start of 2010, valid contracted areas approached nearly 12 million sq km (4.6 million sq mi). In addition, more than 10,300 valid contracts for offshore acreage were in place at the start of 2010. While new deepwater production is masked by the greater volumes of new and ongoing shelf production, the balance is tilting towards the critical point where deepwater and ultra deepwater will dominate. This third phase of offshore exploration was ushered in during 2006, with the Tupi discovery in Brazil, which was a forerunner of a number of significant discoveries dominated by oil and liquids.

New reserve additions via exploration efforts 2005-2009The five-year history of reserves additions shows that onshore exploration efforts are running out of steam. In contrast, deepwater (DW) and ultra deepwater (UDW) combined are becoming the predominant source of new oil and gas discoveries. From 2005 through 2009, giant and significant deepwater discoveries of oil and gas (41 Bboe, 2P reserves) were made in Brazil, the US, Angola, Australia, India, Nigeria, Ghana, and Malaysia. According to IHS, 2P reserves (proven plus probable) represent a 50% confidence level that the reported level is in-place and recoverable. A number of countries recently joined the "Deepwater Club," including Ghana, China, Russia, Mexico, Trinidad and Tobago, Mozambique, Cameroon, Libya, and Cuba. In 2009, the average new discovery size in DW and UDW was about 150 MMboe that is considerably higher than that onshore (about 25 MMboe, 2P reserves). The economic threshold is forcing DW and UDW operators to focus on relatively large prospects and, fortunately, they were able to find these big-scale opportunities. From 2005 to 2009, a number of new plays were discovered in DW settings worldwide. These new plays were not known either on- or offshore prior to 2005, and represent new concepts of hydrocarbon accumulation in deepwater. In Brazil, almost 20 Bboe, 2P reserves were reported discovered in sub-salt Cretaceous deposits of the Santos basin. Another significant oil discovery (3 Bboe, 2P) was made in the Santonian turbidite sands of the Cote d'Ivoire basin in Ghana. A significant natural gas discovery of 6.3 tcf, 2P was made in a Lower Miocene structure in the Levantine basin in Israel. Other new deepwater plays were established in the North Luconia Province (Malaysia), South Makassar basin (Indonesia), Faridpur Trough (India), More basin (Norway) and the Campeche Deep Sea basin (Mexico).

2009 exploration success

Global exploration activity in 2009 located nearly 500 new fields outside of the inland US and Canada, and more than 160 of these were offshore. Not surprisingly, the largest and most prolific offshore producing regions are often adjacent to and/or extensions of onshore petroleum systems. For example, the GoM is a world-class producing region with significant activity by two adjacent countries, the US and Mexico. However, exploration activity in Cuba and the eastern Gulf has yet to impact resource forecasts.

Most finds from 2009 are categorized as "appraising" by IHS, meaning that further drilling is needed to define and target producing horizons, and these efforts are ongoing. More than 50 countries had new offshore field discoveries in 2009 for both oil and gas.

Natural gas offshore continues an upward movement of overall energy contribution with new and developing trends in Australia and Israel, along with longtime contributors in the North Sea.

In 2009, DW and UDW accounted for about 45% of total new discovery volume (about 24 Bboe, 2P reserves) including onshore (35%) and shallow water/shelf (20%). Brazil continues to surprise the world by adding reserves in sub-salt Cretaceous deposits (4 Bboe, 2P). These finds inspired global interest in basins with evaporite deposits, especially those with pre-salt oil and gas accumulations. Although the Brazilian discoveries represent a new play type in the Santos basin, this geologic setting is not unique. Globally, about 30 Bboe were discovered in sub-salt Cretaceous reservoirs.

In UDW and DW of the GoM, six discoveries with reserve sizes in the range from 200 MMboe to 600 MMboe, 2P, added more than 2 Bboe, which was primarily oil. Significant gas discoveries were made in Australia (DW), Israel (UDW) and Venezuela (SW), totaling more than 4 Bboe, 2P of gas. Countries with a longer heritage of offshore production such as Norway, Angola, China, the UK, and a relatively new player, Ghana, added between 300 Bboe to 900 Bboe, 2P.

Offshore drilling activityThe 2008 global recession has had a strong impact on offshore drilling activity, including a slowing of the drilling rate in shallow water and shelf drilling. However, this decline trend in SW started earlier and was caused by various factors including the utilization of new technology, higher drilling success rates, and higher flow rates in deviated wells. Also, shallow water/shelf production in some countries approached an advanced stage of development and does not require extensive drilling programs. DW and UDW diverge considerably: exploration and development drilling trends do not show any indication of a reduction. In fact, 2009 became a record year for UDW drilling, totaling 150 wells. A preliminary well count also suggests strong DW and UDW drilling rates in 2010. On average, through 2005 and 2009, the drilled depth offshore increased from 3,100 m to 3,600 m (10,171 ft to 11,811 ft) and the average water depth from 450 m to 600 m (1,476 ft to 1,969 ft).

SummaryDeepwater and ultra deepwater discoveries will become more important contributors toward maintaining production levels in the face of increasing global demand, especially for liquids. As this exploration effort continues to push the boundaries of existing technology, this same effort could result in international tensions where offshore boundaries overlap and/or fall in dispute. As new technology improves for the high-risk/high-reward prospects of these deep waters, it is likely that older prospects, those closer in and possibly already in areas of developed infrastructure, will be reexamined and reappraised with these new technologies.

Drilling and exploration activity in the offshore environment is slower to respond to changes in commodity prices than those same endeavors onshore. Over time, the fluctuations of price do, however, influence the decision to enter into these substantial investments. Despite the wild ride, the recent rapid changes in commodity prices demonstrated continued interest in the offshore environment.

About the authorsAlex Chakhmakhchev, Ph.D., is senior manager of the Data Advisory Group, IHS. Peter Rushworth is a GIS workflow advisor at IHS.

More Offshore Issue Articles

Offshore Articles Archives

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com