Malcolm Webb

UK Offshore Operators Association

There is little doubt that the oil price has helped to boost oil and gas activity in the UK North Sea. However, the more deep-seated reason behind the current upturn is the achievement of Pilot, the reforming partnership between the UK government and the industry, in transforming industry practices in the UK continental shelf over the past five years.

Frank discussion across all the parties involved has secured a series of voluntary agreements that have given better access than ever before to new exploration and development opportunities.

With this year’s prices averaging just over $50/bbl, companies of all sizes are now seizing the opportunity to raise their investment in this mature basin, and confidence has returned to chase even more prospects.

The surprise tax hit in 2002 led to an immediate decline in UKCS capital expenditure and drilling. The number of new companies entering the basin also fell notably, as investors, unnerved by the sudden change in the North Sea tax regime, switched their attentions elsewhere.

However, activity has now turned around dramatically. Capital expenditure this year could exceed £4.5 billion, up from £3.3 billion in 2004 and 20% higher than UKOOA’s forecast for the year back in January. Exploration and appraisal drilling has nearly doubled since 2002 and should reach around 80 wells this year; development drilling has increased for the first time since 2001 and should yield around 230 wells in 2005. Total spend this year (exploration, appraisal, capital and operational) is at an all time record of more than £10 billion.

UKOOA estimates that by the end of 2005, 24 new projects will be approved this year by Britain’s Department of Trade and Industry, compared with just 14 in 2003, and 16 new developments will have come on stream, up from 11 in 2004.

Operators are also investing massive sums to extend the life of aging assets and infrastructure. Operating costs are expected to be at record levels this year at around £5 billion, £300 million higher than last year.

Pilot projects, including the new infrastructure and commercial codes of practice, the collaborative efforts to bring fallow acreage and discoveries back in to play, the new “stewardship” initiative for mature fields, and the “promote” and “frontier” licenses, are all clearly benefiting the UKCS.

The “promote” license in particular has proved to be a highly successful catalyst for new investment into the North Sea. This innovative approach to licensing has turned around the prospect for activity in acreage that has largely been seen as unattractive in the past.

Just last month, the UK government announced that of the 54 promote licenses it awarded in the 21st licensing round in 2003, 24 have secured financing to press on with actual exploration and, possibly, new development.

These reforms, coupled with a rising oil price and the belief that the fiscal regime was now more stable, have also led to an increasingly diverse range of companies investing in the UK’s offshore oil and gas industry.

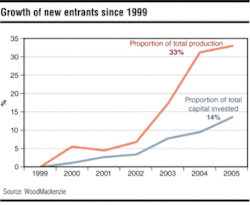

The active participation of the super majors remains hugely important for the future of the UKCS. However, large to medium-sized producers now account for some 40% of UK production, a steadily increasing share as a result of asset transfers and mergers. Furthermore, a significant change in recent years has been the influx of new entrants. In 2005, the 35 companies that have entered the UK market since 1999 will account for about 33% of investment and 14% of total production.

About 120 companies are currently active in UK waters, compared to around 30 in Norway. In the UK, exploration is flourishing, while it remains at a record low in Norway. I believe this demonstrates that mature basins need a diversity of players if all types of opportunity are to be maximized.

The findings of UKOOA’s annual survey of its members’ investment plans are not due to be published until the New Year. However, all indications point to the prospect of similar or even increased activity in 2006, not least borne out by the current high rig utilization rates and tight vessel availability.

While the impact of today’s activity is going to take time to make itself felt upon production, there is no question that the heightened rate of exploration and appraisal is crucial to the province’s future. Provided the UKCS can sustain investment at current levels, the industry believes it will be able to slow the rate of production decline, maximize recovery of existing reserves, and bring substantial benefits to the UK in terms of security of energy supply, balance of trade and future tax receipts.

Furthermore, a thriving domestic industry is fundamental to the success of a new and important business that is developing in the UK. The export of UK oilfield goods and services is conservatively estimated by UKOOA to now be worth £6 billion per annum. This new industry is highly significant in terms of investment and jobs for the UK and has the potential to earn the country major revenues even after indigenous oil and gas production has ended.

The UK’s indigenous offshore oil and gas industry also continues to make a large contribution to Britain’s economy and social fabric. Payments to the UK Treasury are expected to be above £10 billion this year, double last year’s contribution and three times that forecast in 2003. UK oil and gas production currently saves imports of over £30 billion per annum and the industry supports over a quarter of a million jobs across the country.

The fundamentals remain the same. The UKCS is a mature, high-cost basin that presents a well understood set of challenges. Despite this, speculation persists that the UK Treasury is looking to raise revenues by targeting North Sea oil and gas producers. Such a move will destroy the current investment climate and cause damage, which I fear may prove irreparable.