Over 100 contracts awarded to more than 70 E&P companies

Jeremy Beckman,Editor, Europe

Mexico continues to attract new E&P investors after liberalizing its energy sector. The Round 3.1 auction in late March led to the award of 16 contracts in shallow water areas of the Gulf of Mexico, primarily to various international consortia, some in partnership with Pemex. These covered 11,020 sq km over the Burgos, Tampico-Misantla-Veracruz and Sureste basins and carried total commitments for nine exploration wells.

Based on the outcome of this and the two earlier rounds, the country’s federal upstream regulatory authority Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH) expects a total of 26 exploratory wells annually over the next four years, with foreign operators responsible for (43) 44% of all the wells to come. The contracts awarded to date could eventually generate up to $160 billion in investments, assuming 100% success rates.

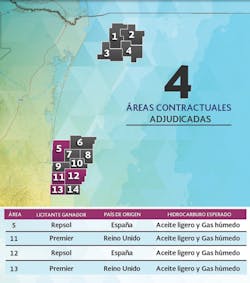

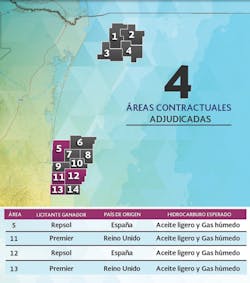

Contracts awarded in the Burgos basin under Mexico’s 3.1 offshore bid round. (Courtesy CNH)

Shortly before the latest auction was staged, CNH President Juan Carlos Zepeda had outlined the background to the energy reform of the country’s upstream sector at the ‘Mexico Day’ investors’ conference in London. The process, which started in 2013, had now achieved maturity, he said, with 12 bid rounds (offshore and onshore) completed prior to Round 3.1, and with CNH, the Energy and Finance Ministries “all in agreement that the system has worked and been successful so far.” At that point Mexico has so far awarded 107 contracts to 73 companies from 20 countries, with the Mexican State entitled to 74% of profits from any ensuing field developments.

This percentage is very favorable for the government, Zepeda pointed out, compared with the state’s take on the US side of the Gulf of Mexico or offshore Brazil. “However, it’s not only about getting the biggest share of the pie – we want to make the pie as large as possible, although that will depend on the scale of future investments.” Spending pledged to date had been “very, very good,” he claimed, with companies committing to drill 129 exploration and appraisal wells (not including the pledges related to Round 3.1). The number of wells planned over the next four years will likely be double previous exploration activity across the sector, he added, with around 44% of the anticipated drilling related to the new E&P contracts.

To attract this level of interest, Mexico has also had to open its waters to international geophysical contractors. Prior to the reforms, Pemex had single-handedly acquired all the country’s seismic data over a period of eight decades, Zepeda pointed out. In the three years that followed the reform, the geophysical industry spent over $2 billion on new wide-ranging seismic surveys – more than triple the amount previously committed by Pemex - and had quadrupled the volume of seismic data over Mexico’s basins. “And this is the best indicator of long-term investment in our E&P sector,” he said, “because those contractors will not see a return on this investment for two or three years…

“We have also seen the first discoveries from wells drilled by foreign operators, earlier than we had expected, on contracts awarded under our first bidding round in 2015.” Results have surpassed expectations: Talos Energy’s shallow-water Zama discovery contains an estimated 2 Bboe in place, while Eni’s appraisal drilling has proven a similar volume in three existing finds.

So why has Mexico been so successful awarding so many contracts, with a high government take, and heavy work commitments? Zepeda highlighted three main factors: first, Mexico’s oil and gas basins are highly prolific, the country having produced 1.6 times more oil than the US offshore since 1936, and two to three times more than Brazil over the same period. “And we have done that with only a tiny percentage of exploration wells compared with those two sectors. So it is not a surprise that now oil and gas companies are discovering new fields in shallow water offshore Mexico.” He also claimed there was a 64% higher chance of making a big offshore find than in Brazil and 77% higher than in US waters.

The second factor is a combination of infrastructure and geography. There are well-established offshore production facilities serving US deepwater fields across the maritime median line in the Perdido Fold Belt. On the Mexican side, Pemex has various discoveries which have not started production, although the company has issued contracts for development. Others that make finds in this area could make use of spare capacity in the US pipeline system, Zepeda suggested.

The countries that import the highest volumes of oil and gas are all to the west in Asia, he pointed out, led by China, Japan, South Korea, and India. “If you operate on the US side, the challenge is moving your oil from the Gulf to the Pacific Ocean. But Mexico’s Tehuantepec Isthmus at its narrowest point is only 200 km [124 mi] wide. Three years ago, Pemex installed a network of pipelines across the isthmus, originally designed to transport gasoline, so the infrastructure is already there to move production from Mexican offshore fields directly to the Pacific.

“For the same reason, Mexico is also a natural gateway for natural gas to Asia. US Permian basin gas currently heads through a pipeline to the country’s east coast for conversion to LNG, and the LNG carriers must then sail all the way to South America or through the Panama Canal. It would be much quicker and cheaper to take the gas via pipelines across the isthmus, liquefy it on Mexico’s Pacific coast, and then transport it to Asia.”

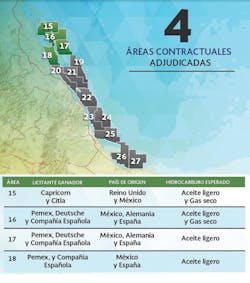

Above: Latest (3.1) contract awards in the Tampico-Misantla-Veracruz basin under 3.1 (Courtesy CNH) Below: Contracts awarded in the Sureste basin (3.1) (Courtesy CNH)

Zepeda also highlighted the strength of the country’s legal framework and energy institutions as a third attraction. “Mexico is the only country that has established regulation of the energy sector in the main body of its constitution. CNH is a constitutional entity, while the government has seven commissions, appointed by the senate, which needs a two-thirds senate vote to push through regulation. This makes for a very strong and robust regulator. CNH’s main mandate is to maintain transparency and accountability in the country’s petroleum sector dealings.”

Urgent need for more projects

BP’s Country Manager for Mexico Chris Sladen said the country’s energy reforms, although a difficult process to enact, had opened the doors for both Mexican and foreign investors. BP itself signed its first Mexican deepwater contracts last year, in company with other majors such as ExxonMobil, Shell, Statoil, and Total. Sladen also noted the participation in the bid rounds of NOCs such as Ecopetrol and CNPC, and “a very healthy number of mid-sized independents backed by very significant private equity investment in the upstream sector.” And BP had been impressed, he added, by the transparency throughout the licensing process and the ease of access to Mexico’s data rooms.

Sladen felt the Energy Reform had been comprehensive, covering the upstream, midstream, downstream and power and had created thousands of new jobs across different parts of the Mexican energy sector. But the reforms had come about because Mexico’s oil production had been declining for over a decade, with gas output down too. “The total oil production is now 1.5 MMb/d lower than in 2004,” he said. At the same time, reserves replacement has been very low – Mexico has been producing a lot, but not replacing it with new discoveries. And the country’s imports of gas and electricity have been rising, with no competition to Pemex…

“Production remains a very massive problem – replacing 1.5 MMb/d is a gigantic task. The best way to do this is via launching big projects, because big problems need big solutions. To replace the lost production, Mexico needs 10 very large new projects per year. We have seen a farm-out in the deepwater Trion field – that could add 100,000 b/d. But the country needs 10 projects a year of this size to get back to 3 MMb/d, not just one. My perspective is that more and larger farm-outs would be a good thing.”

There was room for improvement in other ways, he suggested. “The system could be simplified: there are at present multiple regulators and that can lead to regulatory overlap. Regulation is fine, but let’s keep it simple, well designed and avoid too much paper work, as this needs to be reduced.”

Zama discovery. (Courtesy Premier Oil)

Zepeda said both the government and CNH were working to introduce an electronic version of the bidding rounds in future, which would mean no paper work would be necessary from next year onwards. Both parties were also looking at different ways of attracting fresh finance to E&P in Mexico, he added. However, one of the most pressing needs is to focus on improving Pemex, he argued, because despite the reforms, E&P in Mexico is still not an open competition.

“The constitutional model for E&P creates a double situation. Before we started the 1st international bidding round, the Ministry of Energy awarded Pemex more than 9% of the country’s undeveloped production reserves and the best exploration areas, without any competition – what we offered to the international community was the areas that were left.” One of the priorities now is to speed up the farm-out process, he said, which is as much in Pemex’s interests as those of international investors.

“Pemex faces important challenges. We now have 71 companies working in Mexico but only one – Pemex – cannot go to capital markets to raise money and remains subject to federal constraints.” To change this situation, the government needs to implement further constitutional reforms, he said, and to introduce budgetary controls: “We need to impose capital regulations on Pemex, as on a bank. Instead of subjecting Pemex to federal control, we should impose a capitalization role.”

Whether these changes take place may depend on the result of Mexico’s forthcoming elections, although Zepeda claimed that “regardless of who is elected, the new government needs constitutional reform to make Pemex successful.” Sladen cautioned that whoever leads the incoming administration would have to deal with the country’s underlying production issue “as it will take a lot of investment to turn that around. And for that to happen, Mexico needs an environment that attracts investment – clearly, one company cannot do that by itself. I’d say to the President Elect, you should consider more reforms, particularly to refining and petrochemicals; change the terms that Pemex is operating under; fine-tune investor protection; and [take action to] implement greater simplification.”

Help for Pemex

After the presentations, Zepeda, who has served as President of CNH since 2009, spoke toOffshore about the process leading up to the energy reform. “CNH didn’t start with this reform – it was created in 2004,” he said, “and this has proven to be a good advantage, giving us the time to make the progress we needed and eventually to implement the reforms much faster.” Along the way, he added, the commission had received advice and support for what it was doing from counterpart bodies in Canada and the US’ BSEE, more latterly drawing on experiences from other regulatory authorities in Colombia, Brazil, and the UK.

Today CNH is staffed by 440 professional public servants and has been financially self-sufficient since 2015, charging fees to oil and gas companies in the Mexican sector for performing various services. “We believe we have achieved the size we require and we are satisfied with how the operation works and the breadth of our commercial and technical expertise, and we can outsource extra technical support where needed.”

The extensive marine acquisition campaigns of the past few years by PGS/TGS, CGG and others have tripled the overall volume of Mexico’s 2D offshore data and quadrupled its 3D data bank, he added. “So far, we have not initiated any data acquisition programs ourselves, although at some point, we could invest in new programs.”

In reference to issues raised in the earlier discussion, he reiterated his conviction of the need to transform Pemex into a “real company, capable of raising funds in capital markets, allied to the removal of federal controls over the company’s budget. And once you do that, Pemex’s employees can be paid in relation to the company’s performance. Pemex’s engineers are really good, but they receive a fixed salary as public servants, and there is a real need to introduce incentives and salary mechanisms in a way that better recognizes their performance.”

Zepeda also advocated speeding up the farm-out process, the benefits to Pemex of working alongside major international players including technical competence and technology transfer for deepwater in particular. So far the company had decided to tender five field farm-outs, but only three had been awarded, with no interest declared in the other two. Given the size of the opportunities available this was too few, he said.

“I do see an opportunity to tender a cluster of very large, extra-heavy oilfields already discovered, some of which are in Pemex’s hands, others under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Energy.” All are in shallow water in the Sureste basin, close to the Ayatsil field development. Twenty-two discovered heavy crude fields in the basin have yet to be developed, of which 14 are state-owned discoveries yet to be tendered with total estimated 2P reserves of 796 MMbbl of 10°API oil. CNH estimates the potential combined production if all were developed of 186,000 b/d within a five-year development period. Pemex also has eight heavy crude fields in the area with combined 2P reserves of 627 MMbbl of 14°API oil, and cumulative potential production of 145,000 b/d.

Zepeda pointed out that Pemex has solid experience of heavy oil production while at the same time Venezuela has been decreasing its heavy oil output. There is demand for heavy oil from the Gulf of Mexico, he added, with many refineries equipped to handle it along the GoM coast.

CNH expects a steady stream of successful discoveries over the next few years following the widespread contract awards. At the same time, new offshore pipelines will be needed to accelerate development of these fields, he suggested, along with the creation of deepwater support infrastructure, probably through a joint venture. A prime candidate could be Matamoros Port which is administered by the state of Tamaulipas, located close to the US border and the deepwater fields in the Perdido Fold Belt.