Russell McCulley

Senior Technical Editor

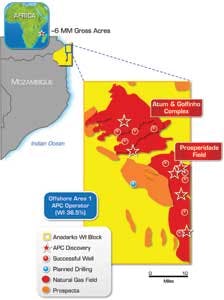

Only a few years back, Mozambique was barely a blip on the oil and gas radar. But a string of discoveries in the Rovuma basin have turned up gas volumes on a scale that could provide long-term wealth for the East African nation - and for US independent Anadarko Petroleum Corp., which operates some 2.6 million offshore acres there.

Since 2010, the company has drilled 15 successful wells and chalked up seven discoveries in Offshore Area 1, which Anadarko operates with partners Mitsui, BPRL Ventures, Videocon, and PTT E&P (Mozambique's Empresa Nacional de Hidrocarbonetos will carry a 15% interest through the exploration phase). The discoveries to date in the Prosperidade and Golfinho/Atum complexes have pushed resource estimates in Area 1 to 35-65 tcf of recoverable gas and nearly 100 tcf of original gas in place.

Late last year, Anadarko signed a heads of agreement with Eni, operator of the adjacent Offshore Area 4, setting the stage for the coordinated development of the reservoirs that span the two blocks. Anadarko issued FEED contracts for an initial four-train onshore LNG processing facility, expandable to 10 trains, as well as offshore installation. Also in 4Q 2012, the Mozambique government granted Anadarko permission to develop a 15,000-acre plot on the Afungi peninsula, where the LNG plant will be located.

Anadarko's exploration campaign in Area 1 will likely continue throughout 2013 and much of 2014, says Frank Patterson, VP of international exploration. Meanwhile, the company has launched an exploratory drilling program offshore Kenya, where it holds operating interest in about 5 million acres.

The activity has placed Anadarko at the forefront of East Africa's deepwater frontier. The company is using its experience in other frontier regions - most notably, the Jubilee development offshore Ghana - to fast-track Area 1 and ship Mozambique's first LNG cargo by 2018.

"We have a lot of experience with these types of developments, so we've been able to kind of compress this," Patterson says. "We understand how we want to develop the fields, and the engineering teams and contractors are working hard on the planning."

Mozambique's domestic gas market, particularly in the north, where the LNG complex will be located, is negligible; the country generates enough hydroelectric power to make it a net exporter of electricity.

"The primary vehicle will be LNG export," Patterson says of Area 1 output, noting that the company's license partners have strong ties to markets in Asia. "There may be some ancillary uses once it's up and running - power generation, maybe fertilizer," he says. "There are a lot of options available, because we've definitely found enough gas to support 10-plus trains here."

Something big

Anadarko can trace its fortunes in Mozambique back about a decade, when the company's new ventures team began taking a close look at the geology of the Rovuma basin. "This was one of the only Tertiary basins, a big river basin, that had really been unexplored," Patterson says. Upon examination of the handful of 2D seismic surveys that had been conducted in the area, "we saw an extension and compression fold system - interesting things on seismic that indicated that you had a pretty good sand system in play. The big question was: did the petroleum system work?"

The team "worked up a proposal and management liked it," he continues. "It was true wildcat exploration. The industry as a whole recognized the potential of the area, I think. But it appeared to the industry to be very small gas. And so commercializing it was going to be a challenge. We saw that there might be some larger opportunities there, and that there might be some liquids associated with it as well."

Anadarko acquired the block in December 2006, brought in partners, and shot 3D seismic. "When we started getting the 3D in, it started to unfold. Things started to get even more interesting," Patterson noted. "To be fair, we didn't recognize how big it could truly be on the 3D. We started seeing things we liked, put an exploration plan together, and brought a rig in from the Gulf of Mexico," Dolphin Drilling'sBelford Dolphin.

"To be honest, the first well, the sands were thicker and higher quality than we expected. We drilled a structure, thinking this was the predominate play, and when we got to the base of the structure we went into a thrusted area just below the structure and found what appeared to be a stratigraphic trap," Patterson explained. "And that's really what blossomed out into the massive size, the stratigraphic trap associated with the front of this system. It's very large, it's very low dip, thick and continuous reservoirs. And once we started seeing that come about, that's when this thing turned into what is probably going to be among the biggest and best LNG project in the world."

"It's not so much that the wells were extraordinarily thick," Patterson adds. "They were high quality, in thick sands. But what really got us going here is the areal extent of this thing. You could drive from The Woodlands to NASA" - two Houston-area locations about 50 mi (80 km) apart - "and still be on the field."

The size of the prospect became apparent with a string of 2010 and 2011 drilling successes at the Windjammer, Barquentine, and Lagosta prospects. "At that point, we recognized that we probably had something really big," he says. "So we focused a lot of effort last year on getting the appraisal work done. We brought a second rig in" - Transocean'sDeepwaterMillennium - "for the testing program." The Golfinho and Atum discoveries followed, which formed a second major complex fully contained within Area 1.

Early drilling at what would come to be known as Prosperidade - the name was selected by Mozambican schoolchildren in the coastal village of Palma - was a "learning" process, Patterson says, with the first few wells coming in at a cost of $50-60 million each. "We've now gotten the drilling cost down to about half of that, especially on the appraisal wells in the main part of the field," he says. "That's translated into a couple of things. It's really good efficiency on the part of the drilling department. And as we go to develop this field, the development costs are coming down."

Transformational opportunity

That development will entail multiple trains, each with a capacity of 750 MMcf/d of gas and each connected to between 10 and 12 wells. "These wells are going to be capable of flowing between 100 and 200 MMcf/d," Patterson says. "We'll have redundancy on the well count to make sure that we keep the facility full. Because the sand quality is so high, and the connectivity is high between the wells, we've been able to reduce the number of wells for the field development, and we believe the first eight to 10 years of the life of the field can be developed subsea, from the field about 30 mi (48 km) in to the shore. That eliminates the need for floating production systems, where you would bring the gas to the surface, compress it, and move it on. But we'll likely put floating production facilities over it later in life for compression."

Anadarko's development costs in Mozambique have been helped by the fact that the partners encountered few technical challenges. "It's a relatively straightforward development," Patterson explains. "On the water, it's technology that we've already used at (the Gulf of Mexico's) Independence Hub and at Jubilee. And we're using equipment that we have a lot of confidence in. Onshore, it will be a large LNG complex that's developed in stages - a continuum of activity until we build out to 10 trains."

With each train designed to process up to 5 MM tons/yr, that means Mozambique could soon be producing 50 MM tons/yr of gas from Area 1 and Area 4, which would place the nation among the world's top exporters of LNG.

Anadarko is hoping to continue its East Africa success offshore Kenya, where the company has shot 2D seismic and "a significant amount" of 3D, Patterson says. Following flow tests at Prosperidade and Golfinho/Atum last December, theMillennium was mobilized to Kenya to drill the Kubwa and Kiboko prospects.

"What we're targeting there is a little bit older formations, Cretaceous to Jurassic mostly, whereas in Mozambique we've been successful in the Miocene through the Oligocene, Eocene, and into the Paleocene," Patterson says. "That's a little younger rock than what we're drilling in Kenya. But in Kenya we're in a different basin setting, and we think that there's a reasonable chance that there might be oil or liquids associated with the play, where in Mozambique it's been mostly dry gas."

Back in Mozambique, the biggest hurdle might be the area's remoteness: Area 1 is far from any major city or large port. But the operational hub Anadarko set up in Pemba has blossomed as other operators and service companies gear up for the construction phase.

"For Mozambique, this is a transformational opportunity," Patterson says. "We're moving toward first cargos in 2018, and we very much committed to do it the right way."

The Tullow Oil-operated Jubilee field, where Anadarko holds a 23.49% working interest, was a valuable training ground for the company's frontier ambitions.

"We think that is one of our competitive advantages," he continues. "We've done this now in Ghana and Mozambique. We're working now in South Africa, in the Orange River basin. We see a lot of future in the world, in some of these deepwater basins. And we like to be out there to help find these resources for the world."

Offshore Articles Archives

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com