Christopher Brown - Wood Mackenzie

December 2009 marks the 10th anniversary of deepwater oil production from Angola. Since oil started flowing from Chevron’s Kuito field in late 1999, deepwater production from the country has grown to around 1.5 MMb/d, eclipsing deepwater output from the US Gulf of Mexico and Nigeria, and sitting in second place behind Brazil in the global deepwater oil rankings – a position it is likely to retain through continuing interest and investment.

Deepwater exploration success

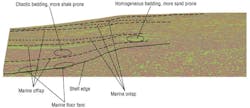

The remarkable story of Angola’s deepwater oil began in the early 1990s when the undrilled deepwater areas of the Lower Congo and Kwanza basins were offered as 17 blocks in water depths up to 1,500 m (4,921 ft). Since the mid-1980s, oil companies - mainly in the US GoM - had seen increasing capability and success in similar water depths. This led to companies seeking further opportunities in the deepwater sectors of already-proven basins, such as the Lower Congo basin of Angola.

It was the majors, with the technological capability and capital to fund these high-risk ventures that secured most of the Angolan acreage in 1993. The blocks that now produce virtually all of Angola’s deepwater oil were all awarded in the 1993 license round: blocks 14 (Chevron), 15 (ExxonMobil), 17 (Total), and 18 (BP). The companies on these four blocks – now collectively known as Angola’s “golden blocks” – have proven up around 10 Bbbl of oil since the first exploration drilling in 1994.

The phenomenal exploration success in the basin in the mid-1990s led to considerable competition for the ultra deepwater licenses – blocks 31, 32, 33, and 34 – which were licensed in 1999. While the average discovery has been much smaller than in the golden blocks, continuing exploration success has led to the discovery of nearly 3 Bbbl of oil to-date.

The 2005/6 licence round that offered the expired portions of the 1993 golden blocks highlighted the value of Angola’s Lower Congo basin exploration acreage. The winning signature bonuses for blocks 15/06, 17/06, and 18/06, ranging from $900 million to $1.1 billion, stunned the industry, but reflected the fierce competition and the perceived prospectivity.

Developments

Angola has 12 major deepwater projects onstream, exploiting 35 fields that initially contained 6.5 Bbbl of oil. Companies raced to get production onstream as exploration costs could be recovered from each block’s first development. The country’s first deepwater developments were Chevron’s leasedKuito FPSO (1999), Total’s Girassol FPSO (2001), and ExxonMobil’s leased Xikomba FPSO (2003).

Since 2004, production capacity has increased dramatically with projects from all four golden block operators. Chevron has brought the BBLT and Tombua Landana compliant towers onstream, two of the tallest man-made structures in the world, while BP, ExxonMobil, and Total have started production from a further seven FPSOs. Also, importantly for Angola’s capacity-building ambitions, this decade has seen its national oil company, Sonangol P&P, bring its first deepwater development, Gimboa, onstream – with the technical support of Statoil.

The development of Angola’s deepwater reserves consistently puts it at the forefront of technology, specifically in the FPSO and subsea sectors. Total’sGirassol FPSO, onstream in 2001, was the largest FPSO of its time and ExxonMobil’s Kizomba A FPSO, onstream in 2004, remains the largest.

Deepwater production still rising

We expect production to continue to rise, as companies are still to produce over three quarters of the reserves on Angola’s golden blocks and with BP and Total also looking to exploit the reserves on their respective ultra deepwater blocks 31 and 32.

However, Angola’s OPEC membership and particularly its position as OPEC chairman in 2009, is limiting the country’s current production by 10% to 15%. We anticipate, based on our global outlook and country specific consideration that some restriction on Angolan deepwater production is likely to remain until 2012. In addition, the only new production in this period will be from the ramp-up of Chevron’s Tombua Landana development, which came onstream in September 2009.

We expect production to surge in 2012, due to the expected lifting of OPEC constraints, new projects coming onstream, and the country’s first commercial gas production. The new oil production will come from the ramp-up of Total’s block 17 Pazflor development from November 2011 and BP’s block 31 PSVM development from December 2011.

A major milestone will be achieved when the country’s first commercial gas production begins to supply the under construction Angola LNG plant and local power plant, at the start of 2012. The feedgas will come from associated gas from all of the country’s deepwater fields, as well as those in Chevron’s offshore Cabinda concession. We estimate that the deepwater developments will supply a combined 800 MMcf/d, once the LNG plant is fully operational.

The oil price crash of late 2008 has delayed many projects and has impacted Angola’s deepwater production outlook for 2013 and 2014. With typical deepwater field decline rates of 15% to 20% after several years of plateau, new fields must be brought on- stream to maintain production totals. This should have been possible given Angola’s lengthy list of probable projects (projects that we consider likely, but have yet to receive sanction) that hold over 5.7 Bbbl of oil. However, the oil price uncertainty has led the majority of companies to revisit development concepts or to retender in order to drive costs down. Consequently, in the last 14 months only one project has received sanction – ExxonMobil’s Kizomba Satellites Phase 1, which will develop 280 MMbbl of oil reserves and is due onstream in 2012.

Post-2014, production is expected to increase again because of the large project inventory and ongoing exploration. To support this, there will need to be considerable investment in Angola’s deepwater sector over the next few years.

Companies to double investment

Over the last 10 years, companies have poured over $46 billion into Angola’s deepwater developments. Over the next decade, we expect expenditure to be in excess of $105 billion. The principal drivers of this doubling of expenditure, in addition to the global rise in capital costs, is not a dramatic increase in the number of developments but rather a move to deeper waters and an increased proportion of local content, which both increase unit costs.

The steepest increase in costs comes from the subsea sector, where the capital investment will triple over the next 10 years, compared with the past decade. This is predominantly because five of Angola’s 11 major planned or under-construction projects are in the ultra deepwater, three in BP’s block 31 and two in Total’s block 32. We expect these projects to cost approximately $20/bbl, which is $4 – $5/bbl more expensive than a typical large deepwater development – most of which is attributable to increased subsea costs. The higher subsea costs are partly because of the smaller and more geographically dispersed fields increasing the quantity of subsea equipment. The discovery size in the ultra deepwater typically is half that of the deepwater. Also reflected in the high subsea costs is the requirement for advanced subsea technology to handle the increased water depth.

Despite capital costs now declining globally, Angola’s increasing local content is keeping costs high. Not only is Luanda the world’s most expensive capital city, the limited port facilities and yard space makes building and assembling equipment in-country very costly.

Drilling costs in Angola are expected to plateau as many of the rigs used by the operators are fifth and sixth generation. The costs of these rigs have not reduced significantly, due to the specialist technology and long contracts. Hence, the increase in drilling expenditure is a direct result of an increase in the number of anticipated wells. Capital expenditure on facilities, especially newbuild FPSOs, is expected to remain relatively static.

Towards the end of the 2010s, we expect future development concepts to center around tying fields back to existing developments, rather than the installation of new facilities. Therefore, we expect the demand for subsea equipment in Angola to remain high, as will the demand to drill wells. However, investment in facilities, especially newbuild FPSOs, is likely to be limited after 2020, unless a new frontier opens.

Overall, the need for specialist technology and drive for local content means capital costs in Angola often do not follow global trends. However, the country’s massive reserves base and need foreign investment continues to make it attractive to the oil majors and national oil companies alike.

2020 and beyond

There is still considerable potential in the deepwater. Wood Mackenzie’s exploration service anticipates there are 8.7 Bbbl of yet-to-find oil in the Lower Congo basin’s Tertiary play, between 2010 and 2030. In the ultra deep, BP and Total continue to explore their respective blocks 31 and 32, with several wells per year. In the deepwater, Eni, Total, and Petrobras all have started exploration drilling on their respective blocks 15/06, 17/06, and 18/06. We expect to see reserves growth from aggressive drilling programs on all three blocks, given the 21 commitment wells and $3.1 billion signature bonuses paid for the three blocks in Angola’s 2005/2006 licence round.

With high signature bonuses, high development costs, and seven to 10 years to first oil, the corporate landscape will continue to be dominated by the majors and NOCs. Beyond 2020, we still expect four majors – Total, ExxonMobil, Chevron, and BP – to be dominant, especially Total as it has the strongest deepwater exploration portfolio. However, we will begin to see an increasing presence of Sinopec, through its Sonangol Sinopec Ltd. joint venture, because of its presence in blocks 15/06, 17/06, and 18/06.

Outside of the country’s prolific Lower Congo basin acreage, the Kwanza basin is attracting interest as a result of the huge pre-salt discoveries in Brazil’s Santos basin. However, with few wells targeting the Kwanza basin’s pre-salt, it is poorly understood. Nevertheless, with 10 Bbbl of remaining reserves and nearly the same again in yet-to-find potential in its Lower Congo basin, Angola’s deepwater will remain the focus of majors and NOCs for many decades to come.