Editor's note: This story first appeared in the November-December 2022 issue of Offshore magazine's first annual Offshore Oil and Gas Executive Perspectives Special Report.

By Jeremy Brown, Luciano Di Fiori, Maurice Fitchett, Elif Kutsal and Micah Smith, McKinsey & Co.

In most pathways toward net-zero emissions, investments in crude oil may be needed until at least to 2040 to ensure energy security for citizens globally. Lower-emitting deepwater basins can play a role in satisfying energy demand while reducing global average emissions.

Oil demand and supply outlook

Modeling the outlook for demand, McKinsey Energy Insights’ Global Energy Perspective 2022 report explores global energy trends under several scenarios, anticipating a peak in oil demand between 2024 and 2035. Common across all these scenarios is that additional supply will be needed to meet demand and offset the natural decline in current online production. New supplies are expected to come from various sources, including OPEC, shale oil and offshore basins—both shallow and deepwater.

Deepwater emissions advantage

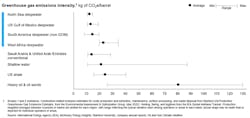

Deepwater basins are expected to meet 7 million of the 24 MMbbl/d of new supply sources needed by 2040, based on large resource potential and low total unit cost (average below $50/bbl). Moreover, McKinsey Energy Insights’ Operations and Emissions Benchmarks report indicates that deepwater basins are among the world’s lowest-emitting production sources, with the North Sea, US Gulf of Mexico (GoM), Guyana and Brazil presalt as standouts (Figure 1).

Several factors underpin this lower-carbon potential:

- High-production throughput at each location that minimizes the number of energy-intensive processes required to bring on new supply (drilling, facilities installation, fluid processing);

- Minimal routine flaring, with sale of most natural gas produced into local market;

- Efficient, modern facilities that minimize methane leakage; and

- Active decarbonization efforts by operators (mostly majors, large independents and national oil companies with aggressive emissions-reduction targets).

Spotlight on the largest deepwater basins

Norway is one of the lowest emitters globally, with environmental regulations such as a CO2 tax on petroleum activities and a ban on non-emergency flaring. It also has the structural advantage of access to “clean electricity” from vast hydro and wind infrastructure, making the case for offshore electrification far more compelling. Additionally, common operatorship across most assets helps drive efficiency and expertise sharing in the basin. UK emissions intensity (while low compared to other resource types) remains higher than Norway’s, mostly because of higher flaring and lower electrification from shore.

For the US GoM region, prolific basins with high- and ultrahigh-pressure reservoirs, combined with modern and efficient facilities, make the GoM a lower-emission resource. The Inflation Reduction Act also couples development of offshore wind energy through lease sales (targeting 30 GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030) with oil and gas lease sales in US GoM, on top of expanding government incentives for carbon capture and sequestration.

Off South America, large-scale developments, relatively fewer and high-production wells, state-of-the-art FPSO facilities with gas reinjection, and strong regulations on flaring make Guyana and Brazil’s deepwater oil fields among the most carbon efficient worldwide. Brazil also benefits from one of the world’s largest carbon capture, utilization and storage programs and a dynamic local gas market. Further decarbonization potential is possible with increased FPSO electrification and energy efficiency. Guyana’s upstream CO2 efficiency should also benefit from Exxon Mobil’s future plans to pump up to 50 MMscf/d of associated natural gas to onshore facilities, for local and export use.

Among the largest four deepwater oil basins globally, Nigeria and Angola have the highest average emissions intensity, mostly driven by flaring and fugitives—a result of legacy assets designed to produce oil and flare the lower volume-gas that cannot be used for fuel or injection. This offers a large decarbonization potential. However, lack of gas-processing infrastructure, limited access to markets and lack of regulatory incentives make it hard for operators to capitalize on these decarbonization possibilities.

Potential Implications

This lower-carbon potential matters both for the many oil and gas companies investing in deepwater (especially those that have announced net-zero emissions targets) but also for the climate. Optimizing the supply mix to include lower-emitting oil is important to meet global oil demand while minimizing emissions. Equally, an absence of continued investment in deepwater assets could reduce production from lower-carbon operations. As is now increasingly clear, every ton of avoided emissions is critical to a successful energy transition.

References available upon request.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge Adam Davey and Stacey Wilding for their contributions to this article.

About the authors: Jeremy Brown is a consultant in Houston, Luciano Di Fiori is a partner in Houston, Maurice Fitchett is a consultant in Amsterdam, Elif Kutsal is an associate partner in London and Micah Smith is a senior partner in Dallas.