Fixed platforms remain important production facilities after more than 60 years

Today’s multiple options for producing oil and gas from deepwater reserves still anchored by the welded tubular steel platform jacket, deck, and surface modules

The offshore industry’s ability to drill successfully in increasingly deeper water has almost always exceeded its capacity to produce oil and gas from the discovery wells.

The lag interval, however, has generally lasted for only a few years, at most - that is, close enough for producers to be confident in acquiring offshore acreage in record water depths and risk drilling away with the assurance that new production technology should arrive in time to make the risk acceptable. New technology has enabled wells to be produced efficiently, safely and with little or no environmental impact.

Today’s development strategies for deepwater discoveries vary, depending on reserve size, nearness to infrastructure, operating considerations (such as well interventions), economics, and the operator’s interest in establishing a production “hub” for the area. These systems all involve floating structures, as opposed to subsea production systems located on the ocean floor and operated independently or as components of floating production hubs.

Deepwater production structures today include:

- Fixed platforms (e.g.,Bullwinkle) - The offshore production mainstay since the 1930s, but since that time much longer and more elaborate, with economic water-depth limits of about 2,000 ft (610 m).

- Compliant towers (e.g.,Petronius) - Floating platforms permanently anchored to the bottom. May be considered for water depths of about 1,000 to 2,000 ft (305 to 610 m).

- Tension-leg platforms (e.g.,Brutus, Magnolia,andMarco Polo) - Known as “TLPs,” these structures are attached to the bottom with tendons held in tension. Are used frequently in 1,000- to 5,000-ft (305- to 1,524-m) water depths.

- Spars (e.g.,Genesis, Devils TowerandRed Hawk) - Buoyant structures shaped like a spar (a single, large-diameter cylinder), with a functional deck mounted on top (Figure 1).

- Semisubmersible production units (Including the world’s largest purpose-built facility of its type, the 59,500-tonThunder Horse production, drilling, and quarters (PDQ) unit). Many others are modified older semisubmersible drilling units. With the increase in new technology, these former drilling units have been fitted with workover rig and well intervention equipment and can be permanently moored in a field usually producing from subsea facilities.

- Floating production, storage, and offloading (FPSO) systems - Ship-shaped vessels with storage and some treatment facilities. Serves both floating and subsea production arrays. May be used in water depths ranging up to and beyond 10,000 ft (3,048 m).

While both spars and semisubmersible production units can be installed in water depths of up to 6,000 ft (1,800 m) or more, the FPSO is most often used in conjunction with both fixed and seafloor facilities to produce oil and gas from deepwater and ultra-deepwater fields, particularly in West Africa, off Brazil and in the North and Norwegian seas.

Floating systems buoy production scene

Various energy market analysts and consultancies update semiannual outlooks on the deepwater drilling and production market due to the unparalleled growth both in the types of drilling rigs and of production facilities designed for increasingly deeper water.

For example, in its outlook for spending in the floating production market for the period 2007-2011, Douglas-Westwood, a highly respected UK-based market research, analysis, survey and strategy consultancy, recently noted that FPSOs dominate the floating market, with more than 175 FPSO deployments worldwide at year-end 2006. This, they said, was 50% more than all the other floating production systems - TLPs, spars and semis - put together.

For the forecast period, Douglas-Westwood researchers predict total spending of more than US$38 billion, with FPSOs representing by far the largest segment of the market at 75% of the total.

As noted earlier, subsea systems are generally multi-component seafloor facilities that allow production in water depths that would normally preclude installing conventional fixed or bottom-founded platforms. Subsea systems are divided into two major components: the seafloor equipment and the surface facilities. The seafloor array includes one or more subsea wells, manifolds, control umbilicals and flow lines, among other facilities. The surface component includes the control system and other production equipment connected by gathering lines from the subsea wells and installed on a host platform in shallower water set many miles from the actual wells.

Operators in the industry’s early days were not as fortunate in their options for developing production found by discovery wells. Offshore production meant one thing: fixed platforms.

Jackets and more jackets

Beginning in the 1950s, the prefabricated steel tubular platform jacket served as the foundation for modular, above-water production equipment arrays, including removable drilling rigs, “dry” wellheads and deck-mounted process equipment. The jacket’s legs also served as ocean-bottom tie-ins for subsea pipelines back to shore.

Later, according toPioneering Offshore: The Early Years, a just-published history of the offshore petroleum industry covering its beginnings to the mid-1960s, such fixed platform designs, pioneered by companies like Brown & Root and J. Ray McDermott & Co., were deployed in larger and longer versions around the world, which gave birth to ever-heftier marine heavy-lift equipment. Also, as platform fabrication became more competitive, construction yards sprung up in many countries, giving the “float-over” transportation industry, which moved such structures out of the shipyard and over oceans to their offshore installation sites (Figure 2).

“In a typical shallow-water offshore installation, a crane barge lifted the jacket from a transport, or ‘carry’ barge, and set it on bottom, after which the leg pilings were driven. The crane barge then set the topsides section-made up of modules of 250 tons or less-on top of the main piles to be welded into place, often with the help of divers...A few years later, crews began welding deck sections, each with topsides equipment completely preinstalled, to the top of the jacket, which they then welded to the piles. This transferred wave-induced overturning loads from the template to the piles.”

Initially, the book points out, platform jackets were towed out to their locations atop dumb barges, and then manhandled by derrick barge cranes to the bottom for securing with piles. That method segued in later years into floating the jacket out, grabbing it with cranes, then turning it upright via controlled buoyancy prior to sinking it to the seafloor. Some deepwater platforms even were built in several pieces that were floated to the platform site, flooded individually, and then fitted together atop the largest, which sat on the sea floor.

In the industry’s sparse beginnings, both exploratory and development drilling often were conducted atop single, all-wooden piled platforms. As better steels were alloyed, operators and offshore constructors switched to tubulars fabricated into jackets and other components. But other materials weren’t ruled out altogether for platform construction. In Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela, the infestation by wood-eating organisms in even creosoted wooden structures spawned the use of concrete drilling and production structures, which continue to be used there today.

“Meanwhile, because steel experienced a high corrosion rate in the lake’s brackish waters, at least one company, Superior Oil, called on McDermott to develop a platform jacket made of lighter, slower-to-corrode aluminum alloy. McDermott responded positively, and both old and new operators in the lake quickly went the aluminum route. Beginning in 1957, McDermott built more than 40 aluminum platforms in its Louisiana fabrication yards, barging most of them to Venezuelan waters.”

Bringing home the ‘bacon’ offshore

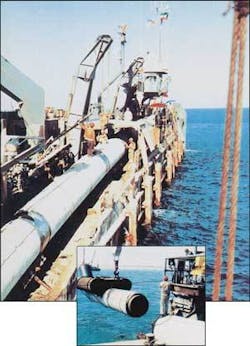

While early offshore operators offloaded production into barges and small tankers via storage tanks erected on platform decks, it wasn’t long before marine construction contractors drew on their hard-won experience with laying pipe beneath rivers, inland bays and lakes, and ultimately pushed the process into the open water offshore. Large, complex marine pipe-lay and pipe-bury barges, coupled with better welding, pipe-coating and line-weighting technologies, resulted in an expanding global offshore pipeline installation market for contractors around the world (Figure 3).

“Because they simply had to, offshore operators and marine constructors developed the technology needed to lay pipelines in deep, open-water areas of the Gulf. But like many offshore technologies, marine pipelining grew slowly - along water-depth lines - in length, diameter, and sophistication.”

Today, of course, few long, large-diameter trunk lines are built offshore, particularly when deep and ultra-deep water is concerned. In such cases, subsea producing formations are connected to the aforementioned floating production systems via both short and long gathering lines that draw production from subsea wells. Additionally, some deepwater floating facilities are connected by long export umbilicals to platforms in shallow water, which in turn are connected to shore by large-diameter transmission lines.