Major overhaul of licensing, tax, red tape

Jeremy Beckman

Editor, Europe

Brazil plans to open up more offshore exploration acreage over the next few years via regular, pre-announced licensing rounds. The government is also looking at other measures to revitalize exploration drilling, which has slumped in recent months, and sustain the country’s production line of offshore development projects in the years ahead. Speakers at the recent Think Brazil seminar in London outlined the various initiatives and reforms either planned or under way, as the government bids to promote a more business-friendly environment.

Last year, Mattos Filho, Veiga Filho, Marrey Jr e Quiroga Advogados became the first full-service Brazilian law firm to open a branch in London, based in the city’s financial district. The company has long experience of legal issues affecting Brazil’s E&P sector, related to matters such as tax, industrial action by unions, local content, or interpretation of offshore concession contracts. According to Partner Giovanni Loss, Brazil is a world leader in litigation with a large volume of disputes, although in the oil and gas industry’s case, the outcome is usually positive, he claimed. One of the more recent in the country’s upstream sector involved two separate oil spills in 2011 and 2012 from the Frade South field, 120 km (75 mi) offshore in the Campos basin. These triggered civil actions by the Ministério Público Federal, with Brazil’s National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (ANP) accusing operator Chevron of covering up the extent of the spill. In 2013, Chevron agreed to settle the claims, reportedly paying $41.6 million.

Oil and gas companies looking to enter Brazil do so either by participating in bid rounds or acquiring an asset. Until around 2008 there was little significant offshore merger and acquisition activity, Loss pointed out, as at that time the country was very much dependent on Petrobras, which was not prepared to sell big assets. That changed when Statoil acquired outright ownership of the Peregrino heavy-oil field, 85 km (53 mi) offshore in the Campos basin, with China’s Sinochem Group later taking a 40% interest in 2011. Two years later, Petrobras agreed to sell its 23% stake in the Parque das Conchas (BC-10) project to operator Shell.

Activity has stepped up recently in producing fields, with Petrobras agreeing to transfer operatorship of Lapa and a stake in Iará in the presalt Santos basin to Total under an alliance arrangement, and Statoil paying Petrobras $1.25 billion for an operated stake in the BM-S-8 concession in the same basin, containing a large part of the presalt Carcará oil discovery. Petrobras is in negotiations for further asset sales as it looks to reduce its debts, although some of these transfers are being challenged in Brazil’s courts (as was Carcará’s earlier this year by the country’s National Federation of Oil Workers).

ANP-approved asset sales, not just those involving Petrobras, have been more frequent of late in years when Brazil has not staged an international bid round, Loss said. The government only decided to hold these rounds on a regular basis, he added, following the giant presalt oil discoveries. Now, with a greater need to bring in foreign companies due to Petrobras’ financial struggles, ANP and the government plan to stage more bid rounds, more regularly over different offshore/onshore areas, with 10 rounds scheduled during 2017-19, one of which has already been held. This year alone 295 blocks will be on offer, which Loss pointed out compares with 155 blocks offered across the rest of Latin America over the last five years. And to save time, the qualification process will now be performed after blocks have been awarded, not before as in the past, although applicants must be careful to compile the correct documents, Loss stressed.

Among the other changes, it will no longer be mandatory for Petrobras to participate in bids, although the company will retain the right to apply for inclusion in the more attractive production-sharing arrangements. In addition, the new government, led by President Michel Temer, is working on investor-friendly measures such as more realistic levels of regulation and a lower mandatory local content percentage in offshore projects. It has also been more proactive in holding dialogue with potential investors, Loss claimed, and has formed a study group to examine different areas of opportunity. Among these are opening up Brazil’s gas sector, with an increased focus on gas projects. One of the main reasons is the country’s long-standing reliance on hydropower, which can be severely impacted if the rainy season fails to deliver.

Opening the presalt

“This is a very exciting time for Brazil,” said Décio Oddone, Director of ANP, “with the largest consultation under way in our entire oil and gas history…Currently Brazil has around 300 exploratory blocks under concession, and we want and need to increase this number.” The contracted areas cover a total of 255,000 sq km (98,456 sq mi), but exploration has barely scratched the surface of some of the country’s 29 sedimentary basins, he pointed out, with less than 30,000 wells drilled throughout Brazil’s 78-year E&P history. That compares with 60,000 wells across Argentina and other smaller Latin American nations, and more than 60,000 wells annually in the US alone. “We want to stimulate exploration all over the country,” he said, “and to more than double the number of exploratory blocks.” Brazil’s needs are growing more urgent, with only five exploratory wells drilled during the first five months of this year, and not a single discovery. “That trend cannot continue,” Oddone warned.

The initial presalt discoveries a decade back led to discussions on how to explore and develop such huge reservoirs, leading to different types of production-sharing contracts being implemented solely for presalt areas. The huge salt layer prevents oil from seeping and guarantees the quality of the crude underneath. “This play is a cash cow,” Oddone said, “with some of the best wells delivering 30,000 b/d - it’s very difficult to find that elsewhere, and we believe reservoirs in the presalt area hold around 30 Bbbl of oil.” And yet the enormous potential has barely been tapped, which is why ANP is preparing for the first time to entrust operations of presalt concessions to companies other than Petrobras, via a bid round to be staged in October.

The government’s previous decision to regulate the Brazilian presalt halted activity in the sector for five years, Oddone said, but it has now changed the presalt law under the E&P consultation process. This is part of a wider-ranging program, he added, to modernize all facets of the country’s hydrocarbons sector in order to encourage badly-needed investment: the process includes Petrobras putting selected upstream and downstream assets up for sale; a first-ever discussion concerning a reduction of royalties on Brazil’s marginal fields; easing local content quotas, and simplifying procedures for identifying local content items in invoices. Further overhauls are under review such as changes to Brazil’s supply chain and how it works, Oddone said, “and we also want to pursue life extensions of our fields in order to maximize recovery.” Brazil is keen to take advantage of the UK’s expertise in this regard, he said.

As for licensing incentives, exploration blocks were previously awarded for two terms with a mandatory well during the second period. Now, Oddone said, there will be a five-year exploratory term without the obligation of a firm well in the second phase. And the system of royalties has changed, with a minimum 5% royalty to be paid compared with 10% previously, and different royalties applied to mature and frontier basins.

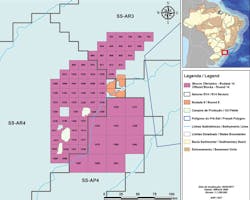

The country’s 14th Bid Round, to be staged in Rio de Janeiro on Sept. 27, will offer 287 exploratory blocks, including offshore acreage in the Pelotas, Santos, Campos, Sergipe-Alagoas, and Espirito Santo basins. It will be followed a month later by the 2nd Production Sharing Bid Round, dedicated to prospective areas close to the major presalt discoveries Sapinhóa, Carcará (block BM-S-8), Gata do Mano (BM-S-54), all in the Santos basin, and Tartaruga Verde in the Campos basin. Three further bid rounds are planned for both 2018 and 2019, including two dedicated to the presalt.

Oddone estimated more than $80 billion in investments could result from the various rounds if subsequent drilling goes on to prove up 10 Bbbl of fresh reserves. Developing these could add 2 Bboe/d to Brazil’s production, he suggested, and might require over 20 drilling rigs and the installation of 15-20 production platforms, 100,000 km (62,137 mi) of flowlines, and 600,000 km (372,823 mi) of pipelines to bring discovered gas to the shore. “This is the largest window of opportunity I have seen in my career,” he concluded, adding that ANP intends to implement a longer-term calendar of bid rounds in future to give the industry greater preparation time.

Petrobras’ action plan

“Last year was very tough for Petrobras,” said the company’s CEO Pedro Parente, “and yet our production reached 2.14 MMb/d, with presalt output above 1 MMb/d, 33% up on 2015. Adding gas, the total was 2.6 MMboe/d, which is remarkable, considering the low oil price environment and the deep cuts globally.” However, a new administration had also taken over, and Brazil was still dealing with the after-shocks of a major corruption scandal. “A very small number of Petrobras executives were involved,” Parente said, “that had joined with bad suppliers and politicians to create the scandal.”

At the same time, he added, there was a challenging scenario in Brazil of a deep recession and exchange rate volatility, while Petrobras was struggling to deal with disputes, high levels of debt, and operating under a tough regulatory framework. “Our obligatory participation in the presalt bid round process,” he said, “was very bad for the country, which [in effect] had to wait for Petrobras to be in a good financial position to drive exploration forward.

“When I arrived, employees felt bad about what was happening in the company.” Before 2015, Petrobras’ debt had soared to six times above the level recorded in 2000, which was far above the industry norm for majors. There were various factors, notably problems with refineries, and the fact that the company was selling oil products below the actual oil price. Collectively, these lifted the company’s interest payments in 2015 to $7.15 billion, Parente said, pointing out that $6 billion would be sufficient to develop a full presalt field system.

However, since the change of president, financial indicators have suggested an improvement in the country’s economy, with inflation in Brazil dipping below target for the first time in many years, lower interest rates of 8%, growth of 0.7% forecast by the Central Bank this year, and proposed labor reforms due to be submitted to Brazil’s senate.

“When I came in,” he continued, “we discussed Petrobras’ debt and its proposed five-year plan. We started redefining the vision for our company as an integrated E&P company, focused on oil and gas, well known for its technical capabilities. Of our 2.5 MMboe/d of production, 95% comes from Brazil and of our 10 Bbbl of reserves, 98% are in Brazil. We also have 2.3 MMb/d refining capacity, 95% in Brazil, and 61 GW power generating capacity in Brazil.”

Petrobras’ two main priorities at present, he maintained, are to improve safety in the company’s equipment and installations and to reduce its interest payments to $2.5 billion in 2018. This will need to be achieved partly via reduced capex and opex, without impacting production targets, and partly via further asset divestments or entering into additional partnerships with foreign oil companies. “We are present in 20 Brazilian sedimentary basins, 316 producing fields, and 131 production blocks,” he said. “We have very extensive experience in partnerships in E&P, and we want to extend these to other areas of the company.”

For 2017-18, Petrobras is targeting $21 billion of ‘sell-offs,’ including pipelines and further strategic partnerships such as those agreed earlier this year with Total and Statoil. By 2024, the company aims to be producing more than 3 MMboe/d. However, Parente acknowledged that some degree of cultural change internally would be needed for these goals to be realized. “We have to explain to our middle managers that we’re here to do business, which sometimes means taking risks. We also need to create the right incentives for our middle management to take the right decisions.”

Exploration roadblocks

UK independent Premier Oil first entered Brazil in 2013, when it was awarded shares in three blocks on the Equatorial Margin under the 11th licensing round - two as operator in the Ceará basin, and one as partner in the Foz do Amazonas basin, which the company has since exited. This is a high-cost frontier basin, explained Dean Griffin, Premier’s head of exploration, with an urgent need for more supporting infrastructure.

To date Premier has acquired 4,500 sq km (1,737 sq mi) of 3D seismic over its blocks in the Ceará basin, where it claims to be the largest acreage holder, including its first pre-stack depth migration dataset. Other operators in the area are Chevron and Eni. The company sees analogues across its blocks with the discoveries along the West Africa Transform Margin: Petrobras has discovered oil nearby, and the company hopes to find more in traps and four-way structures. It plans to drill three wells on its blocks in 2019.

By mid-May Premier had spent $65 million on its Brazil operations, “so it has not been a low-cost entry by any means,” Griffin pointed out. The mandatory large upfront signature bonuses deterred the company from bidding for further blocks in the last licensing round, he added. The regulatory environment could be more efficient, he suggested, with uncertainty surrounding the timelines for getting business done, a slow environmental licensing process, numerous upfront costs, and a lack of clarity over indirect taxes related to E&P operations.

Wood Group, said Gordon Stirling, Development Director and Group Head of Business, started operations offshore Brazil in 2002, providing maintenance support to Petrobras. Two years later the company opened a subsea engineering branch in Rio that designed Petrobras’ first steel catenary riser. The team went onto work on solutions for flexibles, and has since developed a regional capability, working on projects offshore Argentina and Uruguay. Current Wood Group projects in Brazil include modifications to integrated production facilities and subsea work for the latest phase of Statoil’s Peregrino project.

Many Brazilian exploration and development programs are in very deepwater, which is technically demanding to support, Stirling said. The investment climate has been tough, he added, not helped by “inflexible labor laws and complex tax laws.” However, Wood Group does see strong business prospects in increasing recovery by 20% or more from Brazil’s maturing fields through transferring EOR techniques applied in the North Sea.

For Total’s first exploratory well offshore Uruguay last year, Wood Group supplied a real-time monitoring system for drilling risers operating in 3,400 m (11,155 ft) water depth, which Stirling claimed saved four drillstring disconnect operations. “We could also apply this technology to save costs on presalt drilling off Brazil,” he suggested.