Suriname opens to oil industry

By Wiekert Visser, Marny Daal-Vogelland, Lillian Mwakipesile-Arnon

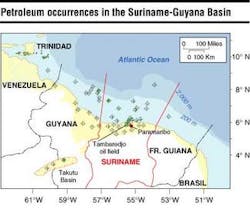

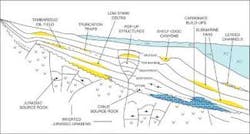

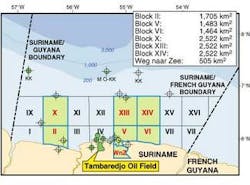

Guyana Basin has all the ingredients to make it a prolific oil- and gas-producing basin, namely world-class source rock, multiple reservoir-seal pairs, and proven stratigraphic and structural traps. How-ever, to date only one producing oil field is in existence, the Tambaredjo oilfield onshore Suriname, with 900 MMbbl stock tank oil in place and 167 MMbbl of reserves. The field currently produces 14,000 b/d, resulting in $31 million of net profit in 2001 for the operator Staatsolie (the state oil company). Exploration outside the Tambaredjo field onshore as well as offshore has been limited.

Traditionally, Suriname has been renowned as one of the world's leading bauxite producers. Alcoa and BHP/Billiton are both still active there. As an oil producer, Suriname has a low profile. Although oil was discovered onshore by Shell in the 1960s, the find was considered non-commercial, as were other discoveries offshore and onshore. In 1982 Staatsolie started to develop Tambaredjo, which was considered a lead by Shell, as a commercial enterprise.

In the 2001 reports of the US Geological Survey (USGS), the Suriname-Guyana basin was qualified as one of the last remaining poorly explored, but highly prospective basins in the world, with an estimated 15 BBOE of reserves to be discovered. Of the 22 wells drilled offshore over an area of 170,000 sq km, 17 had hydrocarbon shows or columns. Many wells were not drilled on structure, due to insufficient seismic coverage and relatively poor understanding of the stratigraphic framework.

Basin development

The Suriname-Guyana sedimentary basin is bound to the south by the Proterozoic rocks of the Guyana Shield, to the east by the Demerara Plateau, and to the west by the Lesser Antilles Arc. The sedimentary wedge thickens northward and reaches over 10 km thickness in the Mesozoic/ Tertiary depocenter, some 150 km offshore. Still further north, the sediment cover thins to a normal central oceanic basin thickness.

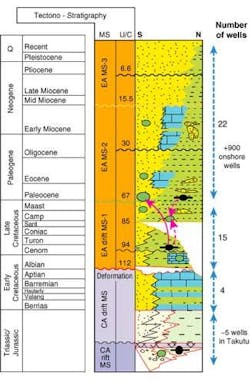

The petroleum geological history begins in the Jurassic when the North Atlantic rift system progressed southward to the Central Atlantic region. The southernmost tip of this rift system terminates in the Takutu Graben, onshore Guyana, where Jurassic lacustrine source rocks resulted in a non-economic light oil accumulation.

This same Suriname rift system was visible for the first time on aeromagnetic data acquired by Staatsolie in 2001. The rift system appears to be present over a significant part of the basin. Most importantly, its presence has never been considered as a serious hydrocarbon play and was not considered in the USGS estimates. However, in analogy with the Takutu Graben and numerous time-equivalent grabens offshore West Africa, the potential seems obvious.

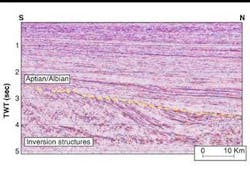

From the Lower Creta-ceous, southern Africa and South America rifted apart due to a counter-clockwise rotation of Africa relative to South America. Because of this rotation, compression occurred in the north between Africa and South America. This compression caused inversion of the Jurassic rift basins in Suriname.

A major peneplenation of the entire Suriname Basin during the Aptian/Albian resulted. The break in the stratigraphy is evident throughout the basin. Thereafter, Africa drifted away from South America, largely along transform fault systems, and the passive margin sequence that developed along the Suriname margin was strongly affected by strike-slip tectonics.

The stratigraphy of the Jurassic rift basins is poorly known in Suriname, since no well penetrations are available. However, from the Takutu Graben in Guyana, a first estimate of the basin fill can be made. Lacustrine source rocks, alluvial fans, and fluviatile deposits, together with volcano-clastics, make up the lower stratigraphy, while salts herald the ensuing marine development of clastics and carbonates.

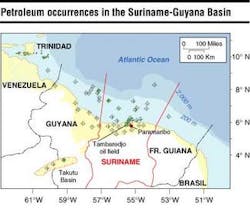

The regional unconformity of Albian/Aptian age is overlain by a classical prograding sequ-ence of clastic sediments, with only short periods of carbonate deposition. The sedimentary environment ranges from terrestrial to deep marine, roughly paralleling the modern day situation.

Numerous onshore and 22 offshore wells provide a reasonable data set to evaluate the stratigraphy. An excellent Cenomanian-Turonian mar- ine source rock overlies the Aptian/Albian unconformity. This rock was deposited over a large part of the basin and has a documented thickness of 50-500 m and total organic carbon contents up to 7%. Biomarker data suggest a marine source rock is present in the Lower Tertiary over part of the basin. Reservoir-seal pairs can be found in just about any age bracket. Oil and gas have been encountered in Upper Cretaceous and Tertiary reservoirs as diverse as valley-fills, point bars, shallow marine sands, and turbidites.

Structuration is intense in the pre-Albian section, with extensional faulting during basin formation, and reverse faulting and folding during the inversion phase. In the Upper Cretaceous-Tertiary, structuration is very mild, and the sequence is largely a monocline. However, new detailed inspection of seismic data reveals that large turn-over structures do exist, which were probably formed as a result of strike-slip movements.

Plays

Jurassic to Lower Cretaceous: Two main play-types are recognized. The first depends on the presence of a lacustrine source of Jurassic age. Reservoirs range from alluvial fans to shallow marine, and even carbonates cannot be excluded. Salt can be seals for the deepest reservoirs, and marine shales for the upper part of the basin fill. Traps are related to reverse faulting and folding. Structures are anticipated to be fairly complex.

Generation of hydrocarbons is thought to post-date the inversion phase, due to deep reburial during the Tertiary. The general concept of this play was proven by wells in the Tukutu graben (Guyana) and by a fairly shallow well, drilled in 1938 in the coastal plain of Guyana near the Suriname border. Here, a blowout of oil and gas was reported.

The second play in the pre-Albian section is a truncation trap against the Albian/ Aptian unconformity. New seismic data show a layered stratigraphy, truncated up-dip and overlain by onlapping clays probably of Ceno- manian age. Charge could be either from the Jurassic or from the overlying Cenomanian-Turonian source rocks. Reservoir type is essentially unknown, but the seismic facies suggests either a deep lacustrine or a marine sequence of alternating sands and shales.

Upper Cretaceous: Four main play types can be distinguished – stratigraphic pinch-out, turbidites, carbonate build-ups, and a wrench-fault play.

Considering the fact that the Upper Cretaceous-Terti-ary shelf sequence is a dipping sedimentary wedge, in which most stratigraphic units thicken down-dip, a multitude of stratigraphic pinch-out and onlap plays can be envisioned. These sand-wedges will all have access to the ubiquitous charge from the Cenomanian-Turonian source rock. New and existing seismic data show numerous examples, several asso- ciated with amplitude anomalies. Overlying the Albian/ Aptian unconformity carbonate build-ups are observed on seismic.

Major wrench-fault systems were identified on the new seismic data onshore and offshore. In the offshore, major east-west running faults pinned the shelf-edge for periods of time during the Upper Cretaceous and Paleocene. During such periods, the shelf is mainly aggradational in character.

Mild, complex rollovers can be seen on seismic data, and counter regional dips are obvious. The sediments within reach of these structures are shelf, shelf-edge, and slope deposits. Reservoir seal pairs are likely present.

Charge is largely from the Cenomanian-Turonian. Considering large differences in seismic facies across the fault-zones, large lateral displacements occurred. Presence of multiple sand-shale sequences, combined with the movements along the faults, makes fault sealing likely. Amplitude anomalies as well as flat events have been observed in the new seismic data.

Tertiary: Numerous plays exist. Coastal sands, sealed by shelf muds, were observed on seismic from the Tertiary zone. Shelf-edge canyons of considerable size are another attractive target. Seismic data suggest canyon fills of up to 200 m thickness, and a width of about 5 km. In addition, numerous pinch-out stratigraphic traps can be seen on the seismic data, several of them supported by amplitude anomalies.

Paleocene: This zone has a proven play in the Saramacca Formation onshore as well as in the shallow offshore. Excellent reservoir sands directly overlay the Top Cretaceous unconformity that provides the seat-seal. Marine shales are the top seal, and the sands pinch-out southward.

The Tambaredjo Field produces 16°API oil from this formation, and lighter oil of 22°API was found in wells in the shallow offshore. At Tambaredjo, sands have a porosity of 33-42%, and permeability in the Darcy range. The oil was typed to the Cenomanian-Turonian source rock by biomarker analyses, and basin analysis shows that the oil must have migrated at least 200 km from the mature kitchen updip into the Tambaredjo trap.

Turbidites: This rock type occurs throughout the Upper Cretaceous and the Tertiary. Light oil was found in Upper Cretaceous turbidites in one well, but sands were thin, and the discovery was deemed uneconomic. Charge is from the Cenomanian-Turonian again, but a contribution from a Tertiary source has been proven by biomarker analyses. During the Neogene, the shelf progrades rapidly northward and shelf-edge collapse is ubiquitous, leading to turbidites downslope. Turbidite feeder channels are easily recognised on seismic as are base-of-slope and basin plain turbiditic complexes.

Detailed mapping is required to mature a prospect, and current seismic data density does not allow this. Amplitude support has been ambiguous, and more work is needed to model the potential of amplitude vs. offset in the Suriname turbidite plays. Charge is no problem, since most of the turbidite objectives are within the Cenomanian-Turonian kitchen area.

Bidding round

The first international bidding round in Suriname is drawing to conclusion. New rounds are soon to follow, and out-of-round opportunities exist. Suriname offers prospective acreage for majors as well as for small independents. While the current round (Nov. 1, 2001-May 2, 2002) focuses on shallow-water and onshore blocks, large areas in deeper waters are available as well.

Staatsolie holds all mining rights to hydrocarbons, and private oil companies can participate in the Suriname oil industry by signing a production sharing contract with Staatsolie. In this arrangement, the oil company explores at its sole risk and account. If a commercial discovery is made and hydrocarbons are produced, the contractor gets reimbursed for its investment (cost oil) and also gets a share of the profit oil. Law guarantees contract stability.

Conclusion

The Suriname Basin is largely unexplored and has a very significant remaining potential. With only 22 wells drilled offshore, of which 17 had hydrocarbons, and a seismic grid of 5-10 km on average, the basin potential has not been evaluated properly. The geological ingredients all point to good prospectivity, except that structuration is mild and stratigraphic traps are more ubiquitous than structural closures, which calls for more detailed seismic grids than are currently available.

Staatsolie developed a number of new geological concepts based on recent seismic and aeromagnetic data, as well as on existing information. Based on this new thinking, a number of untested plays were developed, and this work shows that the basin holds significant potential in stratigraphic as well as structural plays. Charge is no issue in Suriname, and numerous reservoir-seal pairs do exist throughout the Mesozoic-Tertiary sequence.