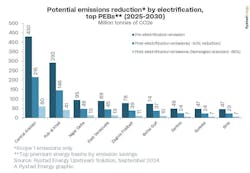

More electrification of offshore upstream facilities could have major impact on emissions, Rystad claims

“Where it’s possible and economically viable, electrification has great potential to lower the industry's emissions while maintaining production output,” said Palzor Shenga, Rystad's vice president of upstream research.

The planning process would require the adoption of optimal technologies as well as an assessment of the costs and strategies needed to maintain a continuous energy supply, particularly in remote locations with limited access to local grids. Other priorities are establishing economic and financial viability of these investments.