GoM deep-shelf incentive fails to overcome decline

“DeepShelf Star” needed to overcome technical challenges

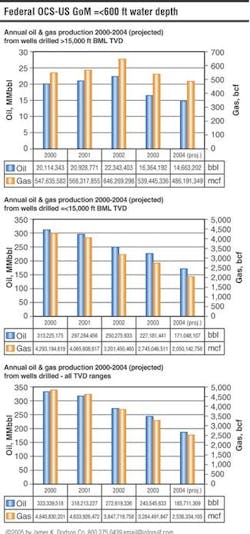

The Gulf of Mexico shelf has a serious problem - declining production thatis not being arrested. Production from shelf wells has dropped from above 333 MMbbl and 4.8 tcf in 2000 to a projected 186 MMbbl and 2.5 tcf in 2004. The 244 MMbbl of produced oil in 2003 is down 27% from 2000. Oil production for 2004 is expected to drop 44% from 2000. Gas production in 2003 at 3.3 tcf is down 1.5 tcf, 31% off the 4.8 tcf produced in 2000.

Production from wells drilled below 15,000 ft showed promise after the US Minerals Management Service instituted deep-shelf royalty relief in 2001. Deep drilling and production began and rose to new heights the following year. However, since the peak in 2002, production from deep shelf wells has declined at a steady rate. MMS data from January-May shows a 34% decline in oil and 25% decline in gas production.

Shallow-shelf production is in decline, and that decline is steadily increasing. Oil production in 2003 is down 27% from 2000 and 2004 production is projected to drop 45% from 2000. Gas production in 2003 dropped 37%, and in 2004 is expected to be down 53% from 2000.

Wellbore impact

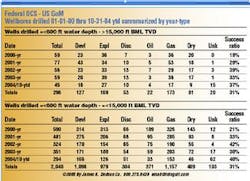

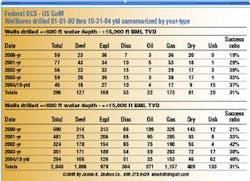

Drillers had their best performance in 2002 when their success ratio for exploration wells drilled below 15,000 ft TVD peaked at 42%. For exploration shelf wells drilled to less than 15,000 ft TVD, the success ratio also peaked, but at 39%. The overall success ratio averaged 31% over the four-year period. Thus far in 2004, success ratios are improving and at 37% and 40%, respectively, are approaching their earlier peaks.

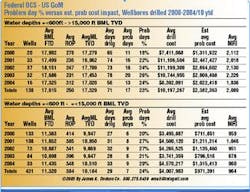

Deep wells encounter greater geo-mechanical complexity, more problem days, and higher cost than shallower wells. In a proprietary performance study benchmarking 138 (47% of total) wells drilled >15,000 ft TVD below the mud line (BML) and 431 wells (21% of total) wells drilled =<15,000 ft TVD BML, these differences became clear. The accompanying chart compares averages of final total depth, rate of penetration, TVD, drilling days, problem days, drill costs, and the Mechanical Risk Index (MRI) of geo-mechanical complexity.

The complexity of the deeper wellbores is more than twice that of shallower wells at averages 2,089 MRI and 964 MRI respectively. Higher complexity results in more problem days, which peaked in 2003 at 20 days for deep wells and nine days for shallower wells in the year 2002. Deep wells average over $10 million to drill, while shallower wells cost just over $4 million on average.

Two other trends of note include:

• Deepening of the average above-15,000-ft well to 10,184 ft TVD

•The lack of significant below-15,000-ft drilling beyond 18,000 ft.

Since deep wells are averaging 17,329 ft TVD, operators are not pursuing the deep-shelf drilling incentive strongly enough to move the average well depth deeper. Many factors affect drilling decisions, with economic potential and cost being in the forefront. Even for prospects with sub-15,000-ft potential, the effects of cost, drilling complexity, and reserve potential are keeping operators from taking on the added risk.

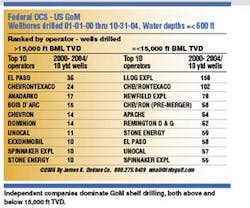

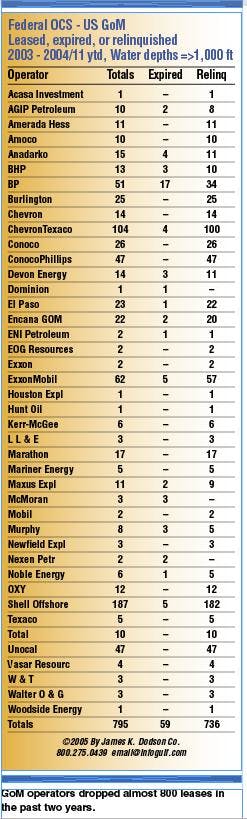

GoM shelf drilling, both shallow and deep, is dominated by independents. Majors are lightly represented with only ChevronTexaco, ExxonMobil, and Shell participating in drilling some of the 2,336 wells cut in the 2000-2004 period. The majors sold most of their shelf properties to independent companies in the 1990s and have been devoting their efforts to deepwater plays and development.

Because of the costs and technologies needed to drill deep in the shelf, few independents have taken on the challenge of drilling below 18,000 ft. Independents have less financial depth than majors, and independents find it difficult to take on the risk of drilling many deep-shelf tests at $20 million or more per well.

This leaves the deep shelf and the MMS’ royalty relief incentive little used. It points to the need for some additional initiative to energize the industry, encouraging it to step forward and to develop practices and technologies appropriate for the deep shelf. The industry also needs to demonstrate commitment to the service companies that are developing the equipment and fluids necessary to tackle the challenges of high pressure, high temperature, and corrosive fluids found in very deep drilling.

History

The MMS’s Deep Shelf Royalty Relief program began in March 2001 to incentivize drilling below 15,000 ft on the GoM shelf in less than 200 m water depth. Production generated by the program peaked in 2002 and continues to fall. Now, both shallow- and deep- shelf production are declining, while drilling remains steady but inadequate to halt the production decline.

The new MMS directive, effective as of May 3, 2004, provides an enhanced royalty relief incentive to explore the GoM shelf in less than 200 m for new deep gas reservoirs at least 15,000 ft TVD BML. The royalty relief is well specific for new gas discoveries and amounts to royalty suspension volumes (RSV) of 15 bcf for wells between 15,000 ft and 18,000 ft TVD BML. The RSV is 25 bcf for wells finding new production deeper than 18,000 ft TVD BML.

If the first qualifying well drilled is 15,000-18,000 ft TVD BML, it will receive a 15-bcf RSV. If a second qualifying well is drilled more than 18,000 ft TVD, the RSV earned is 10 bcf.

Likewise, if the first well qualified is >18,000 ft TVD and a second well qualifies at 15,000-18,000 ft TVD, the RSV can be allocated up to the maximum of 25 bcf. Operators must drill qualifying wells for up to 25 bcf RSV royalty relief under this directive within five years of May 3, 2004. An extension of one year may be granted on application.

The RSV rules treat sidetracks and original wells the same. The sidetrack RSV relief equation is equal to 4 bcf plus 0.6 bcf per 1,000 ft of measured drilling depth to BHL from the kick-off point in the original well. Unsuccessful wells drilled below qualifying TVDs, which are proven not producible with less than 15 ft of reservoir sand, receive an RSV of 5 bcf or boe in gas or oil. If other wells exist on the lease, they can contribute to the RSV production.

The gas price threshold increased to $9.34/MMbtu in 2004 and it will escalate thereafter. This is an increase from the previous threshold price of $5/MMbtu. If the average daily closing NYMEX natural gas price for the spot delivery month exceeds $9.34 or exceeds the inflation adjusted price for the calendar year, the lessee pays royalty on the RSV gas produced.

Prospecting the ultra-deep shelf

Since 1955, operators have drilled 2,234 wells between 15,000 and 20,000 ft TVD BML on 1,046 lease blocks and 148 wells from 20,000 to 25,000 ft TVD BML on 108 lease blocks.

Shell’s White Shark prospect No. 2 drilled on South Timbalier block 174 reached a final total depth of 25,756 ft (possibly deeper) on Feb. 6, 2004. This is the only wellbore drilled in the GoM shelf with a TVD deeper than 25,000 ft. Aside from this well, there has been no prospecting beyond 25,000 ft TVD.

In December 2004, there were 3,770 active leases in the Central and Western GoM; 1,711 of these are undrilled leases held in their primary term. Historical data tells us that the GoM shelf has had many wells drilled to 20,000 ft TVD. Operators have developed, over-developed, and over-produced discoveries. Many operators are depleting leases even faster because of current high gas prices.

Will a royalty suspension policy be sufficient incentive to drill deeper wells? We must go deeper to find new and larger reserves.

At 30,000 ft TVD, the geo-mechanical risk computes an MRI value of more than 6,000. Ultra-deepwater wells with this value indicate a drilling cost in the $40-$60 million range for an ultra-deep exploration well. But, regardless of royalty suspension as a deep well drilling incentive, technology limitations and reliable equipment for safe drilling of these wells requires an ultra-deep incentive solution to the harsh and corrosive environment of H2S, CO2, bottomhole temperatures exceeding 450° F, and bottomhole pressures at 25,000 psi or greater.

Technical limits on drilling fluids, LWD, and MWD equipment require the formation of an “Ultra-DeepShelf Star,” similar to the “Deep Star” deepwater consortium Texaco organized in 1992. The earlier consortium led to a deepwater drilling boom in 1996. All participants of this proposed consortium would have access to the “how-to” with the “have-to-have” technologies for success in the deep shelf.

The GoM shelf as we have known it since 1955 is about to collapse. We are looking at the “sunset,” not the “sunrise,” for wells drilling below 15,000 ft TVD, 15,000-18,000 ft TVD, and 18,000-20,000 ft TVD. Significant support for dry-hole cost is needed for industry to develop the technologies and fund the exploration of the GoM’s ultra-deep shelf. An ultra-deep shelf consortium of operators, service industry, drilling contractors, and government (primarily MMS and DOE) to address the technical challenges of drilling to 30,000 ft in the offshore environment can revive the GoM shelf. “Ultra-DeepShelf Star” could lead to an increase in deep-shelf and ultra-deep shelf drilling, and to a recovery in GoM shelf production.

The “sunrise” for the GoM shelf lies in ultra-deep “moonshot wells” drilled below 30,000 ft TVD.

Editor’s note: Mechanical Risk Index and MRI are trademarks of James K. Dodson Co.