Deepwater operators look to new frontiers

Passive-margin basins emerging as new source of reserve additions and new plays

Kerri Nelson

Michael DeJesus

Alex Chakhmakhchev, Ph.D.

Melissa Manning

IHS

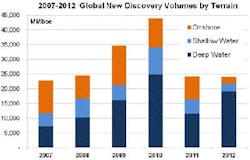

Oil and gas producers frequently ask "where do we go next to find new hydrocarbon reserves?" As researchers, to help answer this question, we began by analyzing available historical discovery data. As a first step to help understand trends as well as to identify priority geographical areas, we analyzed the history of existing discoveries found in the IHS International Field database. This database contains detailed information for more than 28,000 oil and gas fields globally, including 481 deepwater discoveries made during the study period, 2007 to 2012.

Calculating total new discovery volumes and average new discovery size by the type of terrain and by country quickly led us to several important conclusions. First, deepwater has become the predominant source of new oil and gas discoveries worldwide, accounting for more than 50% of all conventional new reserves of 170 Bboe.

Second, six-year trend data shows that average hydrocarbon discovery size is considerably larger offshore, and is especially so in deepwater, where discovery sizes reached a healthy 230 MMboe. This is about a magnitude larger than the onshore average new discovery size for the same period, which is approximately 20 MMboe. Since deepwater operations are extremely costly, the economic threshold is forcing operators to focus their efforts on larger prospects initially. Fortunately, according to our analysis at IHS, they have been able to find significant hydrocarbon accumulations in many frontier provinces.

Deepwater accounts for approximately 7% of total conventional production, in comparison with onshore and shallow water, with 60% and 33%, respectively. However, only 38% of discovered deepwater reserves are currently producing. More than 60% of deepwater reserves currently have appraisal, developing, or discovery status. However, once they are brought into production, these non-producing fields could potentially double production volumes to approximately 6 Bboe by 2020.

Even though recent challenges such as the global economic downturn, credit crises, increased capital costs, and environmental concerns affect deepwater operations, the strong positive growth in offshore E&P trends will likely continue, making deepwater a key contributor to conventional reserve replacement with rapidly increasing share in global hydrocarbon production.

Assessing the geographical locations and geologic targets of recent deepwater discoveries, we find that Brazil continues to deliver by adding primarily oil reserves (26 Bboe) in subsalt deposits of the Santos basin. Interestingly, an analogous subsalt play is an exploration target in the Kwanza basin of Angola, which is located on the other side of Atlantic Ocean.

Substantial oil additions were made in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico, Angola, and Ghana. And an important oil discovery was made in the Fox do Amazonas basin of French Guiana in 2011. For many years, this basin was famous for unsuccessful exploration drilling offshore. However, an attempt that targeted a different stratigraphic play of Turonian age was successful, and resulted in a significant oil and gas discovery estimated at 957 MMboe (proven and probable) recoverable.

This discovery may indicate even greater exploration potential in French Guiana and possibly neighboring countries including Suriname, Guyana, and Brazil. IHS's six-year deepwater discovery outlook indicates that operators searching for oil reserves are most likely to find success searching either in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico, or the Atlantic margin of South America or West Africa.

To the east, new, giant gas discoveries were made during 2007 to 2012 in East Africa (Mozambique and Tanzania), and in the Mediterranean (Israel and Cyprus). As a result, both developments are going to change the energy balance in the region and will provide significant, long-term gas supplies to energy-hungry countries. During the period, several new countries joined the deepwater club, having achieved their first deepwater discoveries. Deepwater drilling rigs finally made their way to inner seas such as the Black Sea and Caspian Sea, which led to discoveries in Russian, Iranian, and Romanian sectors. Other new deepwater countries include Ghana, Libya, China, Cyprus, and French Guiana.

To assess basin and country potential for deepwater discoveries, we analyzed the detailed geologic data stored in the IHS Global E&P Basins database, which contains information on more than 5,100 global petroleum basins and sub-basins, as well as 57,000 field reservoirs containing hydrocarbons. Trend analysis identified the most prolific geological settings favorable for significant reserve accumulation. Our analysis of deepwater discoveries for 2007 to 2012 reveals several trends that can help operators strategize their global exploration efforts.

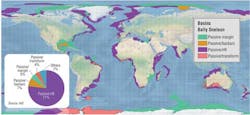

First, the vast majority of deepwater discoveries were made in passive margins, which are continental margins with very little or no seismic or volcanic activity. Based on Bally and Snelson classification, there are four examples of Atlantic-type passive margins, which straddle continental and oceanic crusts. One of them, the passive margin overlying a rift system, accounts for 77% of total new reserve additions in deepwater.

In passive margins, substantial volumes of deepwater reserves occur in stratigraphic traps or in a combination of stratigraphic and structural traps, which requires more sophisticated techniques to uncover. Further analysis of these reservoirs shows that two major depositional facies, turbidites and lacustrine, account for 47% and 30%, respectively, of total new discovery volumes in deepwater.

A passive margin basin type is common not only on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean in West Africa and eastern South America, but also is widespread in the Arctic, Australia, New Zealand, India, and Eastern Canada. Widespread passive margin basins around the globe offer explorationists many opportunities for new hydrocarbon discoveries.

From 2007 to 2012, a number of new plays were discovered in deepwater settings worldwide. These new plays were not known either onshore or offshore prior to 2007, and represent new concepts of hydrocarbon accumulation in deepwater. For example, in Mozambique and Tanzania, approximately 8 tcf of gas was reported discovered in Eocene and Paleocene stratigraphic plays. Another significant gas discovery of 5.7 tcf was made in a Lower Miocene play in Israel and Cypress (Levantine basin).

In Ghana, a significant oil and gas volume of almost 2 Bboe was made in a Turonian stratigraphic and Turonian stratigraphic-structural plays in the Cote d'Ivoire basin. Other new, significant deepwater plays were established in the deepwater off French Guiana, the Falkland Islands, Norway, Iran, Mexico, India and others.

Deepwater challenges

Exploration is risky in many deepwater frontier provinces, with drilling success rates averaging only 10 to 15%. With that in mind, operators carefully select their drilling prospects and make every effort to minimize the risk. Still, only 38% of deepwater newfield wildcats drilled in 2007 to 2012 were technically successful. If an economic threshold for minimum reserve size is applied, then the drilling success rate would drop to 25% globally.

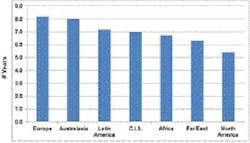

Another big challenge of deepwater projects is their capital intensive nature and technological complexity, which combined, resulted in longer payout periods and lower returns on investment. A typical deepwater discovery requires a development period of five to eight years prior to starting production. When it comes to bringing fields into production, operators in North America are more efficient – averaging five years to production after discovery. The exploration period preceding an official discovery date adds to the total time needed to start production and generate revenue.

The 2008 global recession had a strong impact on offshore drilling activity, which included slowing drilling rates in shallow water. However, this decline in shallow-water drilling started before the recession, and was caused by various factors, including the utilization of new technology, higher drilling success rates, and higher flowrates in deviated wells. Also, shallow-water/shelf production in some countries approached an advanced stage of development during the period, and once in production, these projects do not require extensive drilling programs.

Deepwater and ultra-deepwater diverged considerably during the study period of 2007 to 2012, and exploration and development drilling trends do not show any indication of a slowdown. In fact, 2011 was a record year for ultra-deepwater drilling, totaling 177 wells. The 2011 well count showed indications of recovery, with strong deepwater and ultra-deepwater drilling rates of approximately 500 wells globally, with additional growth in the number of shallow-water wells.

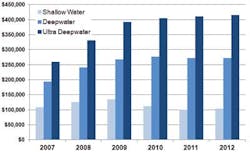

With expanding activities in deepwater, the global supply and demand balance for drilling rigs is very tight. Even though the number of available deepwater drilling rigs is increasing every year and reached a record number of 283 in 2012, utilization rate is close to 98%, which, not surprisingly, caused ultra-deepwater drilling rig day rates to escalate. From 2007 to 2012, ultra-deepwater rig day rates grew from $250,000/day to more than $400,000/day. At present, the global industry needs more drilling rigs capable of operating in deep- and ultra-deep water depths to test numerous exploration targets and to bring the discovered reserves to production.

Political risks

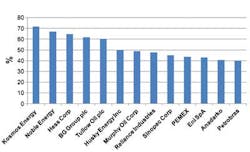

Because deepwater projects are so capex intensive, operators are very sensitive to their levels of risk exposure in the countries in which they operate. To aid in risk assessment, IHS identifies and analyzes the political and commercial risks affecting the E&P climates in more than 120 producing and prospective countries. The IHS political risk analysis service is designed specifically for the international oil and gas industry, and as such, focuses its analysis on factors that directly influence the investment or operational climates of upstream exploration plays, and is weighted for the following criteria:

- Political risks: War and external threats, civil and labor unrest, internal violence and regime instability

- Socio-economic risks: Economic instability, energy vulnerability, environmental activism, ethno-linguistic factionalism

- Commercial petroleum risks: Opposition to foreign investment, repatriation/convertibility restrictions, threat of adverse contract/fiscal changes.

For each country, the factors are quantified and weighted to calculate overall rating and ranking. In the IHS final political risk ranking, each country is characterized by a single value of overall risk. The lower the number, the better (lower) the overall political risk for the country. Further customization of weightings allows country-risk evaluation based on operator strategy and their individual tolerance to different types of risks.

As a result, the final ranking results can be quite surprising, particularly if you weigh heavily the impacts of environmental activism in the US, Brazil, Canada, and Australia. In these countries, while political risk is low, regulatory risk is high, and strict environmental requirements result in higher costs, project delays, and financial losses.

Winning strategy

In 2007-2012, approximately 200 oil and gas companies participated in exploration drilling in global deepwater sectors. These companies spudded about 950 newfield wildcat wells, with a significant portion of new discovered reserves being found by NOCs and independent companies. Moreover, these companies, especially the small and medium independents, demonstrated high exploration efficiencies in terms of drilling success rates and reserves-additions per well.

The key to their success is a clear exploration strategy that focuses on specific basins and play types. Their diversified exploration portfolios in passive margins also include license areas in both mature and frontier basins, which allows them to successfully apply accumulated knowledge and expertise in less explored territories.

These companies have strong abilities to create analogues of proven plays for evaluation purposes, and to apply new geological concepts in old exploration areas. Their flexibility and ability to make moves fast gives independents additional competitive advantage in exploration wars.

Conclusion

Analysis of variable data sets, including global E&P, petroleum basin geology, political risk, costs and fiscal terms reveals remarkable new reserve-growth trends in global deepwater domains, and identifies critical success factors for deepwater operators.

Recent exploration success in deepwater continues to encourage operators to drill in deeper water depths and to explore frontier areas, despite economic, technical, and political challenges.

Global, passive margin basins provide explorationists with many opportunities for reserve additions in new plays. Significant supplies of newly discovered reserves have been found by NOCs in deepwater, who have unrestricted access to first-class resources; as well as by small and medium independent companies who have niche technical or geological expertise, and can move quickly to leverage competitive opportunities. As a result, these independents demonstrate high exploration efficiencies in terms of drilling success rates and reserve additions per well. The key to their success is having clear exploration strategies that focus on specific basins and play types.

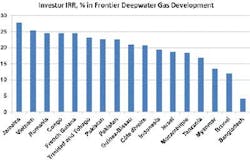

However, the prices of new discoveries remain extremely high because of relatively low drilling success rates on a global level, and escalating capital costs. Operators are facing certain challenges such as tight demand/supply balance for deepwater drilling rigs, elevated political risks, and new, strict environmental regulations and requirements in leading deepwater countries. Gas is becoming the dominant hydrocarbon type in new deepwater discoveries, especially in the Eastern Hemisphere. Available favorable fiscal terms or/and local markets able to consume significant gas volumes are essential conditions for monetizing new gas reserves from deepwater discoveries.

Author's note

In this article, the authors used the IHS "Big Data" approach to understand global exploration trends focusing on deepwater activities. This approach integrates and analyzes various, big-volume data sets to understand global trends and assess risks in a 360-degree fashion, with a goal of helping operators develop a comprehensive, deepwater global exploration strategy that balances risk, prospectivity, cost and other business success factors. Based on an analytical approach, the authors sought to rank and prioritize countries, petroleum provinces and plays. This analysis is also used to identify marketing options for stranded gas or to help operators identify candidates for acquisition by displaying the results spatially. The analysis presented here is based on the IHS International E&P databases, the IHS PEPS (Political Economic and Policy Solutions Service) and the IHS Petrodata services. For this analysis, we used the following definitions for dividing and analyzing trends by water depth: shallow water <= 400 m (1,312 ft), 400 m < deepwater, 1,500 mOffshore Articles Archives

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com