Risk-based inspection integrates asset integrity and classification requirements

Justin Daarud•Mark Tipping• Helen West

Lloyd’s Register

For some two decades, risk-based inspection (RBI) has been embraced by the oil and gas industry to enhance asset integrity. RBI is a risk-based approach to prioritizing and planning the inspection of assets, equipment, and components. Inspections are centered on engineering analysis and the potential for failure. The approach uses past operating conditions and inspection data to make strategic future predictions, capturing a ‘risk snapshot’ in time. This involves the determination of a probability of failure combined with the consequence of failure. At some point in the future, when a risk tolerance is expected to be exceeded, an inspection is recommended to better quantify the state of the component. The inspection itself does not reduce the risk, but it mitigates the uncertainty associated with the current degradation state. This enables operators to better quantify the current damage present in the component and helps engineers make more accurate projections on the asset’s remaining life.

To carry out a successful RBI program, a series of tasks are undertaken alongside a system breakdown. An RBI plan will identify the following essential elements:

- Failure modes and degradation mechanisms

- Inspection scope, including identification of critical locations

- Optimization of inspection intervals

- Inspection processes and techniques.

While the oil and gas industry has employed integrity management and, more often than not, risk-based methodologies and technology to meet safety requirements and serve its operational goals, there is one exception: floating offshore installations. This is an important area where RBI can really help. With ever-tougher market conditions, every difference counts. Greater efficiencies are needed across entire operations and assets, including those with a hull.

Integrating RBI into class

The oil and gas industry has matured differently compared with the marine industry, but the two converge when it comes to floating offshore installations (FOI), such as FPSO assets, FPUs, and FLNG units. FOIs are usually designed and built to marine classification society rules, setting out how operators should maintain the hull and incorporate five yearly prescriptive survey regimes, in addition to the annual, intermediate, special surveys, and dry-dockings. There is no provision for an RBI scheme within the relevant national administration or IMO conventions and codes. Verification ensures that the relevant performance standards are being met; this is often carried out by the class society, particularly in the UK. Integrity management is run separately, focusing on maintaining safe FOI production. What if these two aspects were brought together for FOI hull structures, systems, and associated components?

Introducing a single survey and inspection program that combines asset integrity and classification requirements offers some distinct benefits. For a start, inspection activities would only need to be conducted once, based on engineering needs. Inspection and maintenance regimes would be optimized in line with operations. Costs would be reduced by eliminating unnecessary integrity management activities. Mapping an RBI survey program to suit a facility and an asset integrity program - while also providing justification for the assignment of class - has the potential to save significantly when preparing for surveys requiring cargo and ballast tank entry. Such preparation costs far exceed class survey fees, before considering the lost production time; considerable effort and expense are required before a surveyor even sets foot on the asset. Ensuring all the inspection tasks are coordinated under one plan, and carried out on the basis of engineering needs, is just the sort of efficiency the industry requires.

Safety is also enhanced with a single scheme. Engineering analysis now informs where inspections are concentrated. Operators can look at their assets consciously based on what needs to be done for their assets to remain safe and productive. The risk to personnel is significantly reduced too; people are not being placed in potentially hazardous spaces unnecessarily.

Besides efficiencies and safety improvements, a combined approach can also take into account factors before the FOI went into service. This is a welcome development. Many operators design and build to a standard higher than the class minimum requirement, such as applying better coatings or enhancing the structural detail. The thinking is that exceeding certain standards will allow for higher reliability and a longer time on station. However, operators do not receive any credit from a class perspective for building to a higher standard. Class survey requirements do not recognize different standards; survey cycles and the extent of surveys are fixed.

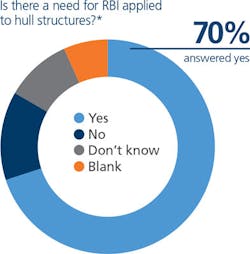

This single approach is not a new idea, but it has become ever more pressing. In 2016, Lloyd’s Register found 70% of clients in a survey answered ‘yes’ when asked if there was a need for RBI to be applied to hull structures. (The survey was conducted at a business breakfast panel involving 50 industry delegates.) In fact, for a decade or so the industry has debated such an approach, but talk has failed to gain momentum. There have been a couple of hurdles. First, FOIs are extremely complicated structures. It is a challenge to arrive at a base line for such assets; there could be hundreds of thousands of inspectable items that all need relating to each other. Achieving this in a manageable way has proved difficult and, consequently, off-putting. Secondly, to adopt an RBI approach for FOIs means questioning tradition and, in particular, perceived regulatory requirements. Mindsets need to change. Ultimately, both time- and risk-based inspection approaches share the same goal, ensuring that offshore units remain within the defined limit state. Another important point is that, hull aside, FOIs are not ships and not subject to the same type of marine regulation. There is scope worth exploring. More recently, class societies have recognized the need to offer an alternative to time-based survey regimes and have been looking to introduce risk-based answers.

Class surveys at set periods defeat the purpose of an RBI approach. To overcome the disparity between the two regimes, greater understanding is called for across the industry. Class societies need to appreciate what FOI operators require and, conversely, FOI operators have to be clear on what classification achieves. Over an 18-month period, Lloyd’s Register has been tackling this matter with a joint team, bringing together expertise from two separate sides of the organization: Asset Integrity and Marine & Offshore. The key has been to understand how classification, verification, and integrity fit together; an exercise in pinpointing the differences between integrity management and classification schemes to arrive at a new service and solution.

Lloyd’s Register is already under contract for two RBI-FOI projects, the first of their kind in the industry. There are some key points worth sharing. A single approach to integrity management and class can be applied at any asset stage. It is currently supporting a newbuild project and an existing unit. Both assets are at fixed locations and the approach is scalable, allowing full or partial RBI implementation. An RBI approach can be adopted for recognized areas of risk only, such as cargo tanks, the topsides that fall out of class or to test unknown costs, for example. Operators of FOIs can try an RBI approach if they are happy with a prescriptive regime for a certain amount of their asset. Or operators can adopt RBI for their entire floating offshore assets.

Critically, FOI operators adopting an RBI plan must adhere to it strictly; late inspection or survey is more likely to lead to class suspension as the plan is now configured for the owner. The roles and competencies of all involved must be clearly defined from the outset. It should also be noted that implementation of an RBI approach is at the discretion of the regulator, who will also determine the extent to which the scheme can be applied. Clarity on this point is key early on.

Informing design onwards

An RBI approach has yet to make a major impact on the design of offshore assets, although progress in this area is happening. Lloyd’s Register has seen the requirement for design-based RBI studies grow in the last few years, an encouraging sign. On the whole, however, RBI is still regarded as a program to consider part way through an asset’s life, despite experts advocating that earlier is better.

Having been involved in RBI at the FEED stage for several projects, the advantages of early adoption are clear - implementing RBI early means that the program is tailored to the specific asset. Risk-based design can help build a more robust structure because input comes not just from an EPC and the owner-operator. Experts in operations and integrity management also contribute. These specialists are familiar with the temperature and pressure spikes an asset can face in service, as well as other damage mechanisms and key considerations. With this knowledge, RBI can identify areas that can be easily redesigned to create a more reliable unit, with less inspection and intervention at the operational stage. Parts of an asset that are prone to fatigue can be afforded greater design attention. Materials can be upgraded accordingly. For FOI hull structures, designers can address common degradation and deterioration mechanisms, such as coating failure, general and localized corrosion, fatigue overloading, and wastage of the positional mooring system. A design-based RBI study may also help decrease build costs, avoiding an over-specification in places or the unnecessary inclusion of corrosion probes or monitoring equipment.

With RBI front of mind from the outset, offshore assets can be designed to minimize the involvement of personnel. This can be as simple as creating the right access points for non-intrusive inspection methods, such as using a camera on a pole. Design tweaks such as these reduce an organization’s safety exposure, labor costs, and potential for human error.

Design is the beginning for RBI. The approach should continue during construction. There will always be anomalies in this phase that might introduce engineering weaknesses. Stress built into the structure is just one example. Outcomes from the construction phase are an additional layer to model for the most effective RBI programs.

Conclusion

An RBI approach is designed to deliver ever greater efficiencies and safety enhancements the longer it is employed. Process, personnel, and technology must all come together to deliver the most robust RBI program, and realize the full benefits.

There are two main challenges in ensuring RBI is a sustainable success. Change of company personnel is proving to be a real stumbling block, especially given the trend for staff to move around the industry every three to five years. Experience and the drive for an RBI program can leave the organization with former employees who were involved in the scheme’s implementation and its day-to-day delivery. Considering the endeavour to establish the program and potential loses, this needs to be carefully watched.

Maximizing value from key metrics and data is also fundamental. This is a key reason behind Lloyd’s Register’s development of Axxim. The third-party software directly embeds into an organization’s existing enterprise asset management application and incorporates decision-making techniques, encompassing RBI, reliability centered maintenance, root cause analysis and failure mode and effects analysis.

Today, clients are gaining the efficiencies of RBI in as short a timeframe as six months, covering the cost of establishing the program quicker than was previously possible.