Africa looking to gas to alleviate continent-wide energy shortfall

Governments working on reforms to bring back investors

Jeremy Beckman

Editor, Europe

Africa has suffered more than most from the slump in new offshore project activity, according to speakers at the recent IP Week conference in London, organized by the Energy Institute. However, there are signs of a pickup in offshore E&P, led by the emerging deepwater plays off northwest Africa, and growing interest among investors in floating LNG, both for export and gas imports.

The brakes on field development offshore West Africa have been accompanied by a slowdown in asset transfers, according to Ade Adeola, moderator of the session ‘Africa: Shaping the continent’s upstream and downstream future.’ Adeola, Managing Director Energy and Chemicals for Standard Chartered in Africa and the Middle East, said only five deals were completed in Africa last year, including financing for Vitol’s participation in the OCTP development project offshore Ghana. Pertamina paid $5 billion to gain entry into Gabon, while late in the year, BP farmed into Kosmos Energy’s gas-rich licenses offshore Mauritania and Senegal. Otherwise, the industry seemed more preoccupied with pressing for reform of Nigeria and Angola’s petroleum tax regimes, Adeola said, adding that “not enough traction was agreed, which left us a little bit disappointed.”

Tayo Ariyo, Shell’s New Business Development Manager Sub Saharan Africa, said that insufficient supplies of energy, in particular gas-fired power, were among the main barriers to the continent achieving its potential. Many Africans still have no access to electricity, she pointed out, and in most African countries electricity is often provided by expensive diesel generators, costing six times what the rest of the world has to pay.

“However, I believe Africa is a land of opportunity,” Ariyo said, “and that gas can power energy access and economic growth.” The discovered gas resources are plentiful, although currently underused in Sub-Saharan Africa, she added. “Studies by the International Energy Agency showed that Africa had enough gas at 2013 production levels to last for 600 years - that compares with 100 years for oil.”

Harnessing this gas, combined with LNG initiatives, could prove transformative, Ariyo claimed, but cautioned that governments in the region should first focus on creating the right conditions for investment: “These include drawing up a clear energy master plan and developing fiscal and regulatory instability - even more important at a time of lower oil prices - security, transparency, and a willingness among governments to co-invest in new energy infrastructure.”

For those countries with less abundant gas resources, the focus should be on cost-effective, small-scale LNG import schemes or co-operating with their neighbors in developing regional LNG solutions, Ariyo suggested, with the industry playing its part by being prepared to invest in the associated infrastructure and technology.

Shell is participating in various gas-to-power ventures in Africa including the Afam power plant in Nigeria, which the company built with NNPC and which now supplies 18% of Nigeria’s electricity. It is also a partner to Total and Côte d’Ivoire’s state-owned Petroci in a new venture that will involve importing LNG to a floating storage and regasification unit stationed off the coast of Abidjan, with the resultant gas supplied to two onshore power plants helping to satisfy the country’s growing domestic energy demand. “This is an example of the type of innovative energy partnerships required,” Ariyo claimed, “and it will be the first regional LNG hub in West Africa. The cost to the government will be around $200 million.

“More partnerships, however, need to be developed between governments and industry,” she concluded, “in order to ensure greater access to energy in Africa. All parties need to look farther ahead to further this process out to 2040-2050.”

Senegal on path to production

Edinburgh-based Cairn Energy operates the multi-national consortium that discovered Senegal’s first two deepwater oil fields. Paul Mayland, Cairn’s COO, pointed out that the company, formed in the 1990s, has typically operated in exploration provinces in four to six countries. “This has allowed us to focus on plays and opportunities of material interest,” he said, “and we are known for being persistent - in exploration, you need to get used to the disappointment of drilling dry holes. However, our track record in South Asia [onshore India, offshore Sri Lanka] and now in West Africa has demonstrated our ability to deliver.

“Over the last five years we have built a more balanced portfolio split between northwest Africa and Ireland/the UK/Norway. We hold significant acreage with various material discoveries, and we are looking to expand the portfolio when justified.”

Mayland said Cairn’s exploration journey in northwest Africa started in 2014, when the company participated in two wells offshore Morocco with state oil company ONHYM and other partners. The arrangement worked satisfactorily, he added, but the results were disappointing. However, Cairn had immediate success offshore Senegal to the south in 2015 where its first wells proved strong oil resources in the FAN and SNE prospects.

“Cairn has been the catalyst for exploration drilling in Senegal,” Mayland said, “as there had been no prior deepwater activity and the country had not had offshore drilling of any kind in 20 years. Since those initial discoveries we have taken the project forward to the appraisal phase, at the same time focusing on cutting the costs of our activity in a lower oil price environment. As a result of various efficiency measures our well costs are now 50% of what they were in 2013-14. Offshore Senegal, this allows us to be in a more attractive place in terms of allocating capital for exploration and appraisal.”

Cairn operates a small staff in-country, mainly Senegalese, and led by an exploration manager. “We have improved the supply base in Dakar to support offshore operations,” Mayland added, “and we have invested in social programs, focused on improving local business and language skills.”

Dallas-based Kosmos Energy has delivered numerous giant deepwater gas discoveries to the north of Cairn’s licenses, both offshore Senegal and in neighboring Mauritania. “We regard ourselves as in partnership with them in terms of opening and de-risking this basin,” Mayland said. “De-risking a discovery, its scale, and the timeframe to development is also becoming more and more important, both for the associated governments and investors. And laying out a timetable early that manages people’s expectations realistically is vital, as there is a temptation to claim each find in a frontier region as a ‘new play’.”

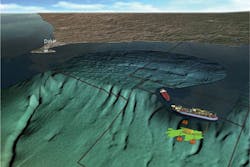

Since 2015, he continued, Cairn has tried to carefully manage its evaluation process with respect to SNE, thought to be the more commercial of the two Senegalese oil discoveries, via step-by-step programs involving additional seismic acquisition and appraisal drilling. SNE’s resource base has been steadily upgraded during the course of appraisal drilling to 500 MMbbl after SNE-4, and may rise further following analysis of the recent back-to-back wells drilled by the deepwater drillshipStena DrillMAX.

“These latest wells are designed to allow us to better understand the connectivity of the upper reservoirs that contain most of SNE’s resources,” Mayland explained. “Depending on the results, the partners will probably sanction more exploratory drilling…we see potential for a further 500 MMbbl in surrounding prospects in the same block.”

Cairn and its partners will look to sanction development of SNE in 2018 or 2019, and it will likely be one of the largest new offshore oil projects at that time, Mayland claimed. He cautioned, however, that “Senegal is a new country in offshore operations, and the process that we are going through with them, this timeline to deliver the steps to first production, is very important. Even in late-2014 we set out a timeline to manage the government’s expectations realistically, saying that first oil would probably not flow before 2021-23. A lot of oil and gas projects have been executed well in terms of the technical challenges, but because the schedule was set out too early and very aggressively, the operators were later accused of being inefficient [for failing to achieve start-up when predicted].”

Nigeria seeking changes

Oando is one of Nigeria’s leading E&P independents. In mid-2014 the company paid $1.5 billion to acquire ConocoPhillips’ Nigerian onshore and offshore business. This included an operated interest in the OML 131 lease, 70 km (43 mi) offshore in water depths of 500-1,200 m (1,640-3,937 ft), and a 20% stake in Oil Prospecting License OPL 214, 110 km (68 mi) offshore in water depths of 800-1,800 m (2,624-5,905 ft). The offshore acreage from this parcel contained six discovered fields and eight prospects with combined potential resources of 281-323 MMboe.

Adewalo Tinubu, Oando’s Group Chief Executive, said the downturn of the past two to three years had been “really tough” for Africa’s commodity-dependent economies, particularly in Nigeria and Angola. “For Nigeria, it’s been a double whammy,” he added. “Two things have happened as the oil price has come down - the economy has tightened, and at the same time, there has been an increase in sabotage and militancy. At the end of last year there was hope of a recovery in the economy, with production in Nigeria trending back up to 2 MMb/d, but the downside risks are still there, with the nation’s foreign currency reserves continuing to decline. The currency issue has caused suffering for our industry.”

For Nigeria’s upstream sector, Tinubu notes that “the question is what to do in terms of investment if prices remain low? Rigs have been leaving, and projects have been put on hold. As for pipeline sabotage, there are solutions - we think we know why this is happening, and we have to try to engage with the situation.”

Tinubu said that in the current climate, “Nigeria’s government is beginning to understand that pushing fiscal rates up for the E&P sector is not the best way to go. But the government needs to also get gas pricing right in order to attract investors, as the country doesn’t have the gas infrastructure that it needs. Also, NNPC owns 60% of the joint ventures that produce 50% of Nigeria’s oil in-country. There is a need to reassess and reduce that ownership level.”

Tinubu added that much of Nigeria’s shallow-offshore plays have now been de-risked, and claimed it was not in the country’s interest for IOCs to retain control of so many of the licenses. “They should be encouraged to divest from these areas,” he said, “as it is easier for independents such as us to optimize these plays. IOCs should focus instead on de-risking Nigeria’s more capital-intensive deepwater plays.”

At the same time, the government should send a signal to the markets that Nigeria is open to business, he continued, by de-regulating the country’s power sector. “Proper power pricing should not be too difficult to achieve. In upstream, the government should establish a consistent structure to give people the confidence to invest, without having to look at newspapers to see what is actually going on.

“The days of government being a paternalistic provider of infrastructure are gone,” Tinubu concluded. “At the same time, the current petroleum minister is focusing on implementing seven big reforms, and that shows we are on the right lines, making investors aware that our issues are being resolved.”