Jeremy Beckman

Editor, Europe

Cost concerns have induced caution offshore Norway as elsewhere, but wells are being drilled and a steady stream of new projects is going forward. Much of the activity has resulted from the Energy Ministry’s conveyor belt of licensing rounds, designed to open mature and frontier basins in order to maximize the country’s offshore resources.

One of the most active respondents in recent years has beenFaroe Petroleum, which has amassed interests in 35 Norwegian licenses and which recently discovered Brasse, the largest new oil find so far this year offshore Norway.

The company was originally formed in 1997 in the Faroe Islands as Føroya Kolvetni to participate in the first Faroese offshore licensing round in 2000. Two years later, it was renamed Faroe Petroleum as a UK holding company, based in Aberdeen, and the following year was admitted to trading on the UK’s Alternative Investment Market. Soon after, Faroe successfully bid for licenses in the west of Shetland area, and entered Norway in 2006.

Today the company is a partner or operator in over 60 exploration, development and production assets offshore Norway, the UK, and Ireland. Its current production of 7-9,000 boe/d comes from the Blane oil and Ketch/Schooner gas fields in the UK North Sea and the Brage and Ringhorne East fields in the Norwegian North Sea. However, the company’s production is set to double to up to 15-17,000 boe/d following an agreement to acquire DONG E&P Norge’s interests in five producing fields in the southern Norwegian North Sea for $70 million, with combined resources close to 20 MMboe: these are: Ula, Tambar and Tambar East (all operated by BP), and Oselvar and Trym, developed by DONG as tiebacks to respectively Ula and the Harald platform in the Danish sector.

Potentially, Faroe’s Norwegian production could rise substantially higher over the next few years due to its participation in projects such as VNG’s Pil-area development and Statoil’s Njord area re-development in the Norwegian Sea, andCentrica’s Butch in the southern Norwegian North Sea, another tieback to Ula.

“As a producer, our cashflow has been split 50-50 between the UK and Norway,” said COO Helge Hammer. After exiting the high-cost west of Shetland area, where the company participated in long drawn-out and complex deepwater wells on the North Uist and Lagavulin structures, Faroe now focuses in the UK mainly on growing production. “As an explorer, however, we’re mainly a Norwegian player,” Hammer added. “We have had a lot of success in Norway over the past few years, with involvement in nine discoveries, six of which are definitely commercial.

“Norway has operated a very stable fiscal regime for many years, introducing cost recovery measures in 2005 in order to stimulate exploration - this has been very good for Faroe.” The measure consists of reimbursement of 78% of exploration costs the following year. “Our strategy has been to participate in around four-to-five exploration wells each year while at the same time maintaining a strong balance sheet, with limited exposure to development projects. Our finding costs have typically been below $2/bbl.”

Near-field focus

The core of the company’s 35-strong team in Stavanger has worked together for 15 years. Most were previously with Paladin Resources, sold to Talisman Energy in 2005, while others had worked for Statoil and Shell. “We have a really strong group of geologists and engineers,” Hammer said, “with skilled teams ranging from pure exploration to commercial M&A [mergers and acquisition] experts. We think we have done well with what we have.”

Hammer continued: “We do our own seismic interpretation and modeling in-house, with a heavy subsurface focus, and we have participated in every Norwegian licensing round in recent years. We are not very focused on one single geological model and rather than favor a specific technology, we apply many, including state-of the art data processing.”

After its experience on North Uist, Faroe shifted its ambitions in Norway toward lower-risk plays in the North Sea and Norwegian Sea, where most of its licenses are situated. “We are still in frontier plays in some areas,” Hammer said, “such as the Barents Sea, where we will partner Eni later this year in a well on Dazzler, a large horst structure at a far-north location close to the Bjørnoya basin. This year we have also secured frontier acreage offshore western Ireland. But otherwise, all our six-seven planned wells as explorers over the next two years will be on near-field targets.

“At the moment, we only have two more commitment wells lined up on our various licenses. That’s a sign of the times - oil companies have a lot of problems and they are being careful not to commit too much with oil prices still lower. And in joint ventures with oil companies, there has to be a joint decision before drilling can go ahead.”

Brage analogies

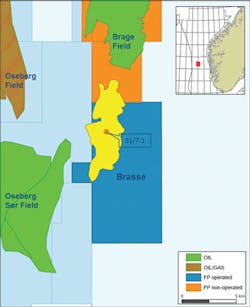

In June, Faroe discovered oil and gas with an operated well on the Brasse structure drilled by the semisubTransocean Arctic in license PL740 in the northern Norwegian North Sea. A side track followed on the southeastern part of the structure, proving hydrocarbons in a similarly-pressured Jurassic sandstone reservoir that is also thought to be analogous to the effective producing reservoir at the Wintershall-operated Brage field to the north.

“As a partner to operator Wintershall we had developed very detailed knowledge of Brage which we had extended into opportunities nearby,” Hammer explained. “That’s how we ended up applying for the acreage containing this undrilled structure. A previous operator had relinquished the license, deeming it too risky. However, we were encouraged by the results from the A18 infill well that Wintershall drilled on the south side of Brage late last year.”

Faroe estimates recoverable reserves in the range of 28-54 MMbbl of oil and 89-158 bcf of gas, which could potentially double or triple its reserves base. Brasse appears to be fully delineated, and the company and partner Point Resources will now assess development options. The discovery is equidistant from Brage and the Oseberg and Oseberg Sør platforms to the west, all 13 km (8 mi) away. Faroe managed to secure the rig for this program at a relatively modest $170,000/d. “My feeling is that we have reached the bottom of the present day rate cycle,” Hammer said, “although it should still be attractive to drill wells offshore Norway next year.”

The company’s candidate prospects for drilling in 2017-18 include Joshi, close to Wintershall’s Maria discovery in the Norwegian Sea; Oshun, near Total’s 2015 Shango gas find on the northern part of the Utsira High in the North Sea; Runge, north of Oseberg; Cassidy, close to Butch; Iris in the Åsgard area of the Norwegian Sea, in partnership with OMV; and Dobby, in the same license as Statoil’s Snilehorn oil discovery in the same sector.

In addition, Faroe may seek to appraise South East Tor in the southern Norwegian North Sea, where Amoco discovered 43°API oil in 1972 with a well drilled on the crest of a salt-induced anticline in both the Tor and Ekofisk formations. Conoco had discovered Tor next door and went on to develop the main Tor field via a platform which is now set to be closed down due to integrity issues, but South East Tor remained fallow, with Lundin eventually assuming operatorship. Last year, Faroe acquired Lundin’s 75% stake, lifting its own interest to 85%, and has since mobilized a team to assess the structure’s commercial potential. Options range from appraisal drilling to assess well delivery followed by a regular field development plan, to a phased approach involving low-cost early production ahead of a longer-term offtake solution, to a joint development with other stranded oil and gas accumulations in the area.

The Norwegian Energy Ministry awarded Faroe six licenses early this year under Norway’s 2015 APA licensing round, and the company is working on more bids for APA 2016. “It is quite a challenge managing our portfolio,” Hammer said, “but we need to keep replenishing it, otherwise our activity might drop off. “There are quite a few interesting opportunities in this year’s round, and we keep surprising ourselves by finding new prospects to apply for every year. However, we have to bear in mind that one day we may run out of good quality new opportunities.”

Njord, Pil scenarios

AtBrage, Faroe is far from a silent partner, interpreting its own data from the 4D time-lapse seismic survey that started over the field in 2014, and which Wintershall is using to identify infill drilling targets to lift production from the low levels the company inherited when Statoil agreed to transfer operatorship in 2011. Last summer, a first infill well on the Fensfjord South reservoir increased output from 12,000 boe/d to 20,000 boe/d, and another productive well was put onstream in January through the production, drilling and quarters platform. The drilling rig has since been warm stacked but should be reactivated next year for further infill activity. “Wintershall spent a lot of money on the integrity of the platform for the long term,” Hammer pointed out.

Toward the end of this year Faroe plans to commit to the development of the 42.5 -51.6-MMboe Butch field via a 13-km (8-mi) subsea tieback to BP’s Ula production complex. Assuming the government approves the program, Butch’s oil will be exported via the Ula pipeline to the terminal at Teesside, northeast England, while its produced gas will be reinjected to improve recovery from the Ula field reservoir.

In the Norwegian Sea, Faroe is a partner in various probable/possible developments. One involves the Njord field where previous operator Nork Hydro started in 1997. There are two main facilities: Njord A, a semisubmersible drilling, production and accommodation platform positioned over subsea wells, and Njord B, a storage vessel. Statoil tied in the Hyme oilfield as a subsea satellite in 2013, and there are other potential satellites nearby such as Snilehorn North. However, a review of the ageing Njord A platform identified widespread structural issues, and earlier this year Statoil shut down production. In August, the facility is due to be towed to Stord in western Norway for further inspections and where much of its equipment will be replaced, upgraded or repaired. The final investment decision is currently set to follow in early 2017.

Faroe has a 25% stake in the2014 Pil/Bue oil discoveries, 60 km (37 mi) southwest of Norske Shell’s Draugen field, which inspired an upsurge of industry interest in this part of mid-Norway, and 32 km (20 mi) southwest of the Njord field. The first well on Pil encountered oil and gas in the same Jurassic Rogn formation that has been so productive at Draugen, but follow-up wells on other prospects last year based on the same geological model were disappointing. “However, now we see opportunities in other prospects.”

The partners have drawn up possible options for a development involving asubsea tieback either to Draugen or the Njord redevelopment, or a standalone FPSO. At this stage, the earliest timing for a final concept decision looks to be late-2017, he added.

Elsewhere in this region, Faroe is a partner in the 2009 Fogelberg gas discovery, where a business case has been drawn up for a three-well subsea tieback to Statoil’s Åsgard B platform. Progress has stalled, however, due to the fact that the Åsgard transportation system serving gas fields in the area will not have available capacity until 2021: the same impasse has affected other commercial gas finds such as Dea’s Zidane. However, the partners plan to look again at Fogelberg this fall, Hammer said, and could approve a field development plan during 2018, allowing the field to come onstream in 2021-22.

Faroe can draw on a $225-million reserve base lending facility and $99 million in cash (not including the company’s recent equity placing of $81 million) to cover its exploration costs. At present, the company has only limited development commitments, although this will change over the next year.

“We have good cashflow from our production and we are keen to grow production further,” Hammer said. “But for the time being Njord is offline, so if we do nothing, we will have no significant increase in volumes until Butch comes onstream in 2019. So we are looking to fill that gap, possibly through acquisition of other producing assets, and that will give us tax shelter for our various E&P programs over the next few years.”