Jim McCaul

International Maritime Associates

Floating production, storage, and offloadingvessels (FPSOs) are the most common type of floating production system. They account for 65% of oil and gas production floaters now in operation or available. The following explores what drives this sector and how many additional units will be required between 2014 and 2018.

FPSOs offer many advantages over other production floaters. They have field storage capability and can be used in locations economically inaccessible to pipeline infrastructure. Water depth is not a constraint – FPSOs operate on shallow to ultra-deepwater fields. They also operate in benign to harsh environments. FPSOs are less weight sensitive than other floating production systems and the extensive deck area of a large tanker provides flexibility in process plant layout.

Surplus and aging tanker hulls can be used for conversion to an FPSO. They can be modified and redeployed following field depletion. Units fitted with quick disconnect turrets can be moved during typhoon/hurricane activity. Leasing of FPSOs has evolved into an industry-accepted procurement practice to transfer financing burden, con¬struction risk, residual value risk, and operational responsibility to a contractor.

But FPSOs also have disadvantages. Subsea tiebacks associated with FPSOs generally bring higher well maintenance costs. Complex turret/swivel machinery used on weathervaning FPSOs is expensive and failure of the turret/swivel can be a major problem. Use of older tanker hulls for conversion can cause unexpected cost overruns and delays. Redeploying an FPSO is not as easy as it may appear. Each field is different, often requiring major modifications to processing plant and mooring system.

The number of FPSOs in operation or available for deployment has increased 96% over the past 10 years. This figure reflects delivery of new FPSOs and scrapping of aging units during this period. The net result has been an increase of 85 FPSOs between the end of 2003 and the end of 2013. With deliveries planned in 2014, the number of FPSOs will increase another 14 units by the end of this year – assuming no existing units are scrapped.

Meanwhile, contracts for 136 FPSOs have been placed over the past 10 years – an average of just under 14 FPSOs annually. But the average disguises some significant variation. As many as 25 and as few as five FPSO contracts have been placed in a single year over the past decade. The low was in 2009, when the 2008-2009 global financial collapse caused a hiatus in orders for all types of floating production systems. The high was in 2010 when Petrobras ordered the hulls for eight serial FPSOs.

These orders have included a wide mixture of FPSOs – from $2 to $3 billion-plus contracts for large complex FPSOs likeEgina, Agbami, and Usan, to small $100- to $300-million units like Balai Mutiara, Front Puffin, and East Fortune. They also include 12 standardized FPSOs ordered by Petrobras from local yards in 2010-2011 for future use offshore Brazil – eight based on new hulls, four using tanker conversions.

Over the 10-year period, 112 of the 136 FPSO contracts (82% of contract awards) have entailed construction or conversion of first time FPSOs. These FPSOs have not previously operated as production units. Another 24 contracts (18% of contract awards) have involved modification of existing FPSOs for redeployment to a new field. Typically the redeployment contract involves modification of the process plant and mooring system, plus general upgrade to the entire unit. The modification cost can easily exceed $200 million.

Planned projects

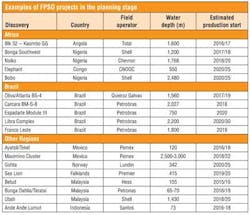

International Maritime Associates (IMA) is tracking more than 130deepwater projects in the planning stage that will likely require an FPSO for development.

Each project in the planning stage includes a wide spectrum of storage size, topsides plant capacity, and mooring system. VLCC-size FPSOs with 100,000-plus b/d processing plants will be needed on major projects in Brazil,West Africa, and the Mexican side of the Gulf of Mexico. Most will be spread moored, while some will be fitted with turret mooring. Smaller FPSOs with 30,000- to 50,000-b/d processing plants will be required for marginal projects in Southeast Asia, North Sea, and elsewhere, most requiring turret mooring systems.

The number of FPSO projects in the planning stage has more than doubled over the past 10 years. In late 2004 there were 58 projects in the visible planning pipeline that potentially required an FPSO as the development solution. By December 2008 the number had increased to 95 projects. Now there are 132 projects potentially requiring an FPSO. These figures reflect the number of projects in the planning stage on each date. Some projects will require multiple FPSOs – e.g., Libra could require up to 12 FPSOs. If the figures represented potential FPSO orders, the growth over the past 10 years would be greater.

Future requirements

Between 140 and 150 additional FPSOs will be required should all 132 currently visible projects proceed to development. But this requirement needs to be adjusted to take into account field development options, project cancellations, project timing, and emergence of "yet to be visible" projects.

- Around 10% of visible projects have several possible production solutions. IMA anticipates that around half of these (or 5% of the 132 projects) will ultimately not produce an FPSO requirement.

- Some visible projects will be cancelled or deferred following additional appraisal. Based on the number of projects included in the 2004 planning list that failed to proceed to development, the company anticipates that 15% of the 132 projects in the current list will ultimately not proceed to development.

- Not all of the visible projects are within the five-year forecast window. Based on an analysis of the planned projects, about 65% appear capable of advancing to the final investment decision (FID) by the end of 2018. The FID in the remaining 35% will likely be after 2018.

- Additional fasttrack projects will undoubtedly emerge over the next several years. Most will involve small- to mid-size FPSOs to exploit marginal fields. Based on FPSO orders placed over the preceding five years IMA anticipates that five to 15 additional FPSOs will be required over the next five years for "yet to be visible" projects.

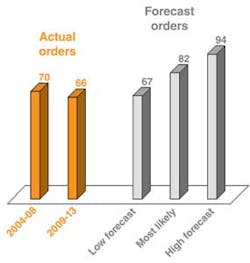

Combining these adjustments, IMA expects a requirement for 67 to 94 FPSOs over the next five years. This is the high and low range of FPSOs that could advance to the FID stage by 2018.

Where the actual number of orders falls within this range will be determined by the underlying market conditions that unfold over the next several years such as the extent to which oil prices increase or decrease, availability of drilling equipment, barriers caused by local content policies, other supply chain constraints, cost escalation, access to project financing, and relative attractiveness of investing in deepwater vs. shale/tight oil projects.

IMA sees the FPSO sector growing at an accelerating pace through 2018. The forecast of 82 orders is 24% higher than the number of orders placed over the past five years. Between 2009 and 2013, 66 FPSOs were ordered. It should be noted that the global financial crisis in 2008-2009 distorts the comparison. The crisis caused a one-year hiatus in orders, lowering the past five year total. In the preceding five-year period (2004-2008) 70 FPSOs were ordered.

But the new forecast of FPSO orders is significantly lower than the forecast made by IMA last year. There the company forecast orders for 100 to 140 FPSOs annually over the following five years, the best estimate being 120 units. Now it forecast 67 to 94 orders, with a best estimate of 82 units.

Why the big drop? Over the past year it has become clear that supply chain and other constraints are much stronger than previously thought. Deepwater project start opportunities keep growing – evidenced by the growing backlog of projects in the planning stage. But capability limitations in the supply chain, increasing project complexity, escalating costs, access to financing and bottlenecks created by local content targets have worsened. These factors have constrained – and will continue to constrain – deepwater project starts.

Another reason for the drop is the growing diversion of oil company available investment resources to shale/tight oil and gas projects. There have been recent examples of deepwater projects being postponed or cancelled as a result of projected project return being lower than alternative uses of investment funds. IMA expects the diversion of resources becoming greater over the next several years.

Based on an analysis of FPSO projects in the visible planning pipeline, the company anticipates that 27% of the projected FPSOs will have 100-150 kb/d topsides plants, 22% 150-200 kb/d plants, 4% 200-plus kb/d plants, and 23% 50-100 kb/d plants. The remaining 24% will be smaller oil processing units or gas FPSOs.

Using FPSO orders over the past 10 years as a distribution benchmark, IMA expects 26% of projected FPSO orders to involve purpose built units, 56% to be based on conversion hulls, and 18% to involve redeployment/modification of existing units.

Purpose built units will be weighted toward larger FPSOs with plant capacity more than 100,000 b/d. FPSOs built on conversion hulls will be spread over a wider spectrum of plant topsides capacity.

Redeployed FPSOs will be primarily in the smaller topsides capacity, with a few in the 100 to 150,000 b/d range.

Projected capex

Capex associated with FPSO orders over the next five years is projected to total $91 billion in the most likely scenario. Around 38% of the capex will be for purpose built FPSOs, 56% for FPSOs converted from existing tankers, and 6% modification of redeployed FPSOs.