Michael Haney

Matthew Loffman

Steve Robertson

Douglas-Westwood

The FPSO supply chain is broken. The floating production, storage, and offloading systems markets will be unable to meetFPSO demand over the next five years unless significant change occurs in an industry increasingly defined by schedule delays and cost overruns.

Industry players understand and accept this position, but until now they have been unable to quantify the effect of these project delays and cost overruns. Success in improving the supply chain model has been limited at best, negatively affecting exploration and production companies, suppliers, and leasing contractors in particular.

The goal here is to quantify these delays and cost overruns, and examine the reasons behind the ailing FPSO supply chain. The role of the oil companies, development complexity, regulation, and conflicts of interest within the value chain are some of the challenges affecting FPSO project execution. Each will need to be addressed if near and medium-term energy demand will be met.

Oil price growth has stopped

The structure and organization of the FPSO supply chain and the entire approach to FPSO development has frequently been questioned. In addition to the "Why do we do it this way?" question is, of course, "Why is anything going to change now?"

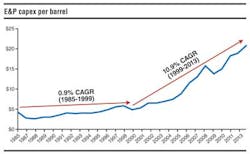

To address the latter question, it is important to consider the health of both the industry and the ultimate "end customer" of the FPSOs, the E&P companies. At first glance, the oil industry and oilfield service industry may appear to be in fine health. Oil prices, while not at record highs, are still in the neighborhood of $90-100/bbl, and overall upstream industry spend is expected to hit record highs this year. Underneath the impressive headline figures, however, is a different story.

The current upstream cycle (2010 onwards) demonstrates very different characteristics to the one that preceded it (2001-2008). During the earlier cycle, prices increased more than tenfold from trough to peak, significantly boosting the free cash flow of E&P companies in the process and to some extent masking the effects of dramatic cost increases and project delays.

While oil price growth has slowed or stopped, oil industry cost inflation has not. In fact, most surveys show that the double-digit cost inflation seen in the last cycle has returned. Operators' costs are rising at a much faster rate than free cash flow. This is not a sustainable. A Goldman Sachs study highlighted the impact very clearly - the returns for oil majors (measured in terms of cash return on cash invested) are at their lowest levels since 1999.

E&P companies will have to do something about cost inflation for projects to be viable. They will not have the luxury of ever-rising oil price increases to mask the impact of project over-runs.

Production industry is broken

Based on research and interviews by Douglas-Westwood with operators, contractors, suppliers, and financers, key contributing factors include: hurried engineering at the front-end; over-engineering during the detailed design phase; conversion scope changes when unwanted surprises occur; lack of clarity relating to contract responsibilities; and construction delays - usually as a result of engineering changes and the requirements to continually build one-off designs. The next question is, "Why is the production industry broken?"

Driven by the need to boost valuations, oil companies tend to approach drilling activity with a keen sense of urgency. Few questions are asked aroundoffshore drillship day rates exceeding $600,000 when large exploration projects are on the line. Specialty drilling contractors usually shoulder a large portion of the drilling workload. On the other hand, oil companies have always had a detail-oriented approach toward production costs as they aim for maximum production and margin on each barrel produced. This helps maintain profitability on long-producing fields despite fluctuations in commodity prices.

As the core competency of oil companies is the production of hydrocarbons, this approach makes perfect sense. Operators involve many decision makers in production decisions, ranging from project decisions to overarching business decisions in the C-suites. As a result, the number of cooks in the oil company kitchen is significantly higher when production is on the menu. In our research, it is clear that company targets can conflict or oppose each other at times. These conflicts add to the complexity of project execution, resulting in negative implications for suppliers and lower project efficiency.

The way in which tenders are presented to leasing and engineering/procurement/construction contractors adds further complication and risk to the supply chain. Oil companies typically perform extensive diligence and analysis when deciding whether and how to develop an offshore field. When they decide to develop, tenders are often issued with a hard deadline, requiring contractors to deliver within short timeframes that can appear arbitrary. Tight deadlines place pressure on the final steps in the process, such as hull and topside integration and commissioning.

Click to Enlarge

About the research

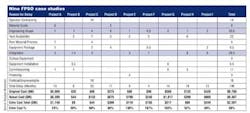

Douglas-Westwood reviewed in depth nine recent FPSO projects. While the FPSOs varied in terms of type (newbuild or conversion), ownership (leased or operator-owned), and geography, there are specific themes that can be drawn from the research. Significant cost and schedule overruns are commonplace and are now standard practice in the market.

The nine projects had a combined cost overrun of 38% and a collective delay of more than 12 years. The most significant cause of delay was integration of hull and topside, followed by yard availability and engineering scope. A total of more than $2.5 billion was spent above budget to bring these projects onstream, with additional costs and delays continuing on two of the projects at the time of writing.

The research suggests that these case studies are directionally representative of the industry as a whole. Of the 45 FPSOs installed worldwide between 2008 and 2012, 30 were delayed, many significantly.

These cost overruns indicate the additional capital required to bring these nine projects online. However, this represents only part of the financial challenges facing oil companies. With each day of delay to first oil, overall net present value of the project suffers. Months of delays can materially reduce field development economics to the point where the field is no longer a viable investment. Lengthy production delays frustrate oil company investors, who want barrels brought to market as quickly as possible to maximize company financial returns.

As the critical decision makers in the industry, oil companies have a responsibility to address and optimize current internal practices, the limitations of which have contributed to project overruns in the past. To some extent, favorable contract terms passing risks to leasing contractors have shielded the operators from the weakness of the supply chain. However, the gap between supply capacity, witnessed by the diminishing appetite of many of the leasing contractors to take on these projects, and demand for FPSOs in the coming years will leave some operators disappointed, and will bring these concerns into sharper focus.

Click to Enlarge

Project complexity

Every offshore field is different and therefore requires different production infrastructure. Each field has particular characteristics; production curve, water depth, oil and gas mix, °API gravity, well numbers and locations, pressure ratings, responses to enhanced recovery techniques, lifetime estimates, and so on. The different nature of each offshore development project has led to a fleet of uniquely designed FPSO solutions. Such a variance increases the complexity of supplying FPSOs; more so than in other areas of the oil and gas, such as drillships and supply vessels.

Field owners need to have comfort that their field is being optimally exploited. This is particularly true of national oil companies who steward hydrocarbon resources in their waters. As NOCs lead developments in critical producing regions, this factor has become more prominent, ensuring that subsea infrastructure, topsides equipment, and FPSOs are designed for the maximum production possible. Strong competition among the majors in offshore plays supports governments' capacities to place stringent targets and other requirements.

Accurately evaluating reservoir potential is an industry-wide challenge. Unique geological features, extended production lives, and lack of information at the start of the evaluation process complicate estimates. Reliance on early and limited data is necessary, but has a strong impact on production infrastructure. A higher proportion of development capital is required up front, and the observed impacts on FPSO design have been negative and severe. Based on limited data at the beginning of the design process, engineering specifications for FPSOs are made to decimal place detail. As production data is added throughout the process, it frequently becomes obvious that the basis of these specifications miss the mark by several orders of magnitude. The inaccuracy of the data underpinning FPSO design is exacerbated by technology innovations and improvements throughout the lifecycle of the field. Due to their extended operational life, FPSOs suffer more than other areas of the industry.

Regulation issues

Regulation of FPSOs is another challenge that will continue to cause serious issues, particularly as deployments become increasingly international, incorporating multiple jurisdictions.

FPSOs can be ship-shaped and make self-propelled voyages, making them subject to certain shipping and marine rules and regulations. Other FPSOs are neither ship-shaped nor self-propelled. Likewise, once in operation the unit is tied to subsea equipment and the seabed, albeit not permanently. In these cases regulation reference is to E&P installations. There is considerable overlap and confusion between these positions. Inconsistent regulatory conditions, combined with increased complexity in field specific solutions, drive the regulatory bureaucracy to the extreme with proportional cost ramifications.

Local content

The FPSO supply chain further suffers fromlocal content requirements. While benefits to local communities must be a priority, the execution of these plans in diverse regions threatens the advancement of technology and supply chain efficiency in critical markets. Reliance on inexperienced shipyards to complete complex integration of hull and topsides has led to eye-watering delays and cost additions in the past five years, and this will continue to grow unless there are significant changes. Related issues around availability of engineers, experience of procurement personnel, and the supply of minor necessary equipment all continue to contribute to complications in FPSO delivery.

Supply chain complexity

The FPSO supply chain is complex and involves a wide range of equipment and service providers. Oil companies contract either an FPSO leasing contractor or a major EPC company to design and procure the FPSO. Major EPC contractors may own fabrication yards and have equipment manufacturing capacity, although much construction work is further sub-contracted to shipyards. Lease operators and EPC companies procure equipment from specialist providers. Suppliers range from international conglomerates to niche and regional players.

With so many players working to bring an FPSO online, project execution suffers as conflicts of interest between parties arise throughout the process. Engineering houses bill hours worked and have professional and financial interests in extending the scope of front-end engineering. Construction yards favor efficient delivery with little interest in adjusting work scope throughout the process. Yards will often have multiple major projects to execute, with scope changes potentially moving an FPSO to the back of the line. Oil companies themselves have an interest in achieving fast first oil, so long as the FPSO is safely integrated, yet still place a high priority on reducing engineering hours and costs.

Organizational learning

The research highlights the lack of institutional experience among FPSO operators. In drilling projects, repeated delivery allows operators and contractors to build experience and develop repeatable practices. However, few companies have completed enough FPSO projects to institutionalize lessons learned. In addition, key FPSO personnel often change firms from one project to the next. These lessons of past projects need to be learned as an industry, if near future demand for FPSOs is to be met.

Project size and nature

Often, the sheer size of the projects brings additional complications. With FPSOs costing hundreds of millions of dollars, lease operators are required to raise such significant volumes of capital that the financial health of the company is at risk on each project. This is not sustainable, even in the short-term. This is particularly true when, after cost overruns are distributed, many projects originally considered quite profitable end up instead making substantial losses.

Shipping industry influence

Many early FPSOs were developed by the shipping industry, and these were often older vessels converted to store oil at relatively low cost. This gave field operators an inexpensive, convenient option to assist in field developments, as well as offering vessel owners new revenue opportunities for older, lower-value assets. The offshore oil and gas industry has developed significantly in recent years, as capacities have increased, depth and formation capabilities have increased, and HSE regulations have gained prominence.

The economics of conversions is further tested by current technology and cost trends. With current complexity of projects and technical solutions, the proportion of topside expenditure compared with the hull is significantly reduced. This further reduces the advantages to ship owners associated with conversions of old tankers. Research indicates that the relative savings associated with conversions will become less influential.

Drilling industry comparison

The high level of oil company involvement in the organization of FPSOs contrasts with thedrilling industry, where operators outsource operations to specialist contractors. Contracting practice allows oil companies to incentivize drillers who offer bundled solutions, limiting the hands-on decision-making involvement of the operators. By shifting administrative responsibility to drillers, the web of decision making has become far simpler compared with the production side. Whether elements of this approach could be transferred remains to be explored. Given oil company culture and typically higher levels of involvement in production decisions, oil companies will need to increase their responsibility for that supply chain, particularly when it breaks down.

Next steps

Re-addressing the "Why is anything going to change now?" question requires examination of the current ethos and belief systems within the supplier community. Offshore production is often conservative in adopting new technologies and practices. A mentality exists that there is no alternative to the current practice, often based on almost mythical stories of failed past attempts at change, or on a handful of individual experiences over the years.

There is little doubt that emotional factors are instrumental in driving contractors' decisions across the board, ranging from equipment selection to evaluation processes. The difficulty now is that demand outstrips supply to the extent that the supply chain simply is not sustainable, and these challenges are increasing, not decreasing. There is a pressing need to address supply chain concerns, and this will involve a serious, rational examination of options with no room for hearsay or hunches.

Approximately 100 new FPSOs will need to be built by the end of 2017, representing a 50%+ growth in fleet size. The supply chain will not meet demand over the next five years or further into the future unless substantial changes are made in the industry.

The industry value chain will need to be restructured. Leasing contractors' FPSOs are major, multi-billion dollar investments. Observing the growth of leasing as a procurement model for FPSOs, contract risk terms equate to operators using some contractors as a bank, hedging their investments. With leasing contractors suffering across the board, there may be an opportunity for them to refocus, potentially separating into technology development and "own and operate" groups.

Project repeatability is another way to improve FPSO supply. Project methods that build on industry knowledge of delivery and operations can improve execution quality and efficiency. The interviews with oil companies and others suggest that beginning each major project from a blank sheet of paper may not be necessary if safe and effective alternatives are developed.

Oil companies have an important role in nurturing the supply chain beneath them, otherwise they will continue to see costs rise with no improvements on overruns. Only 10 or 15 years ago an FPSO would cost tens of millions of dollars; now they cost hundreds of millions. With oil companies seriously examining cost in the sector, there is an urgent need for change in the buying process.

Changes to the regulatory framework could significantly impact the ability of the supply chain to meet demand in the years ahead. Current regulations governing FPSOs are cumbersome and under-developed. With each FPSO treated as unique, relocation and other mobilization are overly complex. This is apparent when compared with drillships, which are typically regulated as part of a class and far more easily mobilized. With industry consensus and effort, improved regulation could help oil companies complete the production phase more efficiently and professionally.

These and other measures may offer hope to the ailing supply chain as demand continues to ramp up. Significant changes and intentional involvement are required from all parties for the FPSO supply chain to be fixed to the extent that upcoming demand is met. The offshore industry has met multiple challenges in the past. Working together, the key players can develop faster and more cost-effective FPSO facilities to meet growing demand.