Saudi Arabia dramatically increases rig count, accelerates offshore development

Barry Jongkees

Strategic Analysis

Oil was first struck in the Arabian Peninsula on March 3, 1938, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has been the centerpiece of the oil market ever since. With proven reserves of 260 Bbbl and a production capacity of 12.5 MMb/d, it has taken up the role of "swing" producer: that is, it has ensured stability of global output by making up for unexpected shortfalls in other countries, as happened during the Gulf War of 2003 or the unrest in Libya in 2011.

However, some analysts have warned that the rapid development of shale oil poses a significant threat to Saudi Arabia's key position in the oil market. As global production of oil is set to increase, its reserve production capacity will become less vital in maintaining price stability. In this light, it is telling that the Saudi oil minister, Ali al-Naimi, said that the kingdom would not increase production capacity beyond 12.5 MMb/d for the next 30 years in contrast to earlier calls to increase output to 15 MMb/d to meet global demand. Simultaneously, however, Saudi Arabia has massively increased the total number of drilling rigs in recent months; this year, the total number of rigs is set to hit a record of 170, nearly double the 88 rigs in October 2012. The spike in the number of rigs as well as the exploration and development of more costly offshore fields signify a troublesome trend: it is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain stable output from the existing wells amidst growing domestic and international demand.

Offshore developments

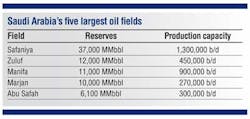

Saudi Arabia's largest offshore oil fields are Safaniya, Zuluf, Manifa, Marjan, and Abu Safah, which together hold a total 76.1 Bbbl in reserves with a combined production capacity of 3.42 MMb/d. These offshore fields represent roughly 30% of total Saudi reserves and 3.8% of daily global demand.

The Manifa field commenced production in April 2013. The field is estimated to be the fifth-largest in the world, with proven reserves of 11 Bbbl of heavy crude oil. The Manifa field has been relatively expensive to develop, by Saudi standards; the investment amounts to $17,500 per peak daily barrel, compared to the $10,000 per peak daily barrel project in Khurais and the incredibly cheap $2,500 per peak daily barrel in the Haradh III zone in the Ghawar onshore field. The reason for the comparatively high investment cost is the construction of a 41-km (25-mi) causeway to link the oil platforms to the mainland, in a bid to avoid damaging the ecosystem and reefs in the area. The field was designed with a maximum production capacity of 900,000 b/d by the end of 2014.

Another technological hurdle relates to the nature of the oil in the field - heavy crude. This variant of crude oil has a higher density and viscosity than light crude, making it harder and thus more expensive to extract. However, for offshore heavy crude wells, there is an advantage that offsets the difficulty in extraction. Heavy crude is typically located at shallow depth, and is less vulnerable to oil spills and other damages. Heavy crude deposits are often located at roughly 3,000 ft (914 m) or less, whereas recently discovered light crude deposits in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico are often in water depths of around 10,000 ft (3,048 m).

The expansion into the Manifa offshore field and the relatively high costs associated with its development reflect the increasing difficulty of extracting crude oil from mature fields. As mentioned, in order to maintain production at roughly 12.5 MMb/d, Saudi Arabia plans to nearly double its total number of rigs this year. These rigs are increasingly located in undeveloped fields, such as Manifa, in order to reduce the pressure on existing fields, including the onshore giant Ghawar. Last June, the kingdom produced 9.47 MMb/d; a decade ago, the same amount was produced with only 60 rigs operating in the country. Only one conclusion can be drawn from this observation: it is becoming increasingly difficult to keep up daily production of cheap, light crude oil.

In 2012, Saudi Arabian oil production hit a record of 11.5 MMb/d. This means that if output capacity remains stable, the excess capacity has shrunk to only 1 MMb/d. Nigeria, a site of frequent civil unrest surrounding its oil production, produces roughly 2.5 MMb/d. This means that in case of supply disruption in Nigeria due to unrest or terrorism, Saudi Arabia is unable to make up for the shortfall on its own.

In order to explain the sharp increase in the number of operational rigs as well as the development of additional offshore fields with higher production costs, it is crucial to understand the political and economic risks facing the Saudi monarchy.

Political risk

Most Saudi oil fields are in the northeast of the country, where the Shiite minority is concentrated. Ever since the 2011 Saudi intervention in neighboring Bahrain, where the majority Shiite population aimed to overthrow the Sunni monarchy, civil unrest in the Shiite regions of Saudi Arabia has increased.

Recent unrest in Qatif led to clashes between security forces and protesters. More than 17 people have been killed in the protests that started two years ago. Qatif is only 144 km (89 mi) from the Abqaiq refinery, the largest oil-processing plant in the world. If civil unrest were to spread and increase in intensity, it is likely that disruptions in oil production would follow. However, the risk of escalating civil unrest is limited, as the state has intervened decisively and consistently to prevent brewing conflict from escalating. It has repeatedly fired at and killed protesters, as in Awamiya on Sept. 26, 2012. It has also started to arrest Shia clerics that speak out against the regime, such as the apprehension of Nimr al-Nimr in July 2012, for whom the regime had issued an arrest warrant in 2009. Shia pilgrims in Medina have repeatedly been attacked in 2007, 2009, 2011, and 2013, sparking protests and unrest in Shia regions. Therefore, civil unrest is limited in Saudi Arabia, but can be expected to flare up during religious events.

The risk of terrorist activities is also limited in the short term, and previous attacks on energy infrastructure have been rare. The most recent serious attempt dates to February 2006, when militants wearing Aramco armor and driving two Aramco vehicles were able to penetrate the first of three security fences before being discovered. A firefight ensued, during which their vehicle exploded. Reportedly, only a small pipeline was damaged, as the vehicles were still in the outer ring of the facility. The response of the state was decisive: three days after the attempt, security forces raided houses in al-Yarmouk and al-Rawabi, killing six militants. As al-Qaeda currently remains heavily involved in operations in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen, it is unlikely to be able to devote significant operational capacity to attacks in Saudi Arabia, meaning that if attacks are planned, they are likely to be small in scale and scope.

Economic risk

The consequences of shale oil for OPEC states are significant. OPEC has already stated that it assumes demand for its oil exports to drop to 29.6 MMb/d this year, 600,000 b/d lower than in 2012, due to increased global oil production. Indeed, Prince al-Waleed recently voiced concern over this trend, stating that lower oil prices will negatively impact fiscal stability, as oil revenues constitute 92% of the Saudi budget. Based on the increase in global oil production, Saudi Arabia should resist increasing its production capacity, as the changing international market makes this unnecessary. At the same time, it is crucial to maintain or increase current levels of exports in order to maintain market share. This brings us to the increase in domestic demand that increasingly burdens Saudi oil production.

Saudi oil production has steadily increased to 11.5 MMb/d in 2012, while output capacity has remained stable at 12.5 MMb/d. Saudi Arabia has stated that it intends to maintain spare capacity of 2 MMbbl to meet unexpected shortfalls.

However, domestic demand for energy has steadily increased over recent years, fuelled by fast population growth. The Saudi population is expected to reach 30 million by 2017, double the number of people 30 years ago. Demand for electricity has increased by 3.15% per year, and it is estimated that peak energy use will be 120,000 MW by 2030, tripling the current peak use of 46,000 MW.

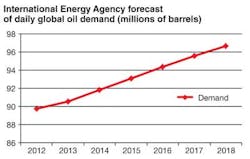

In order to keep up oil export capacity, Saudi Arabia has increasingly sought to replace oil with gas for domestic energy use. As such, a majority of the increase in rig count is dedicated to gas exploration and development. The development of the Manifa field should be seen in this light, as it is set to produce 1.8 bcf/d (51 MMcm/d) of gas. Saudi Aramco recently refocused on development of gas as domestic demand grows. According to BP, Saudi Arabia produced a total of 9.9 bcf (280 MMcm) last year, an increase of 11% year-on-year. During the same time, domestic consumption of oil declined 12.5% from 800,000 b/d to 700,000 b/d. Maintaining export levels will be crucial both for Saudi fiscal stability and global economic growth. Global demand for oil is set to increase, in Asia in particular. By 2018 global daily demand will be 96.5 MMb/d, an increase of 7% over current demand.

Cutting consumption

Based on this data and the rebuttal of alternative explanations for the increase in rig count, the conclusion is that Saudi Arabia finds it increasingly difficult to extract sufficient production out of existing wells. Amid growing global and domestic demand, the country seeks to increase its gas output for domestic use, which explains the spike in rig count in recent months. The same motivations underlie the development of the expensive offshore Manifa field. To maintain production capacity, and its position as swing producer, domestic use will have to increase, as capacity is not bound to increase over the next 30 years.

"Saudi Arabia is the sixth largest oil consumer in the world and this is only set to rise with the kingdom's population set to increase to 36.5 million by 2032," said Ruth Lux, managing director of Strategic Analysis. "Current figures suggest 31.5 bbl of oil are burned per person per year and that 33% of domestic oil consumption is used for air conditioning. In the short to medium term, it is unlikely that domestic consumption habits will change. However, Saudi Arabia's massively subsidized domestic oil consumption is untenably high, and it is not a sustainable energy model for future generations."