Martin Kelly

Wood Mackenzie

Over 100 tcf of gas has been discovered in Mozambique and Tanzania to date. The Rovuma basin in northern Mozambique has emerged as one of the most prolific conventional gas plays in the world. The huge resource base – aside from gas already discovered, there could be 100 tcf in yet-to-find volumes – means that international investors are looking at new licenses, available farm-ins, and merger and acquisition (M&A) opportunities as routes into the region.

But there are significant technical and commercial challenges to bringing the gas to market by the end of this decade. These include addressing issues around infrastructure, government capacity, financing, and a positive outcome to unitization negotiations in Mozambique.

Exploration has been extremely successful to date.

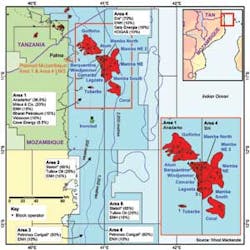

Exploration success began in deepwater East Africa in 2010, with Anadarko's discovery of its Windjammer field in Area 1, Mozambique. This success has continued, with Anadarko adding further discoveries to Windjammer and Eni adding more in Mozambique Area 4. With over 80 tcf found so far offshore Mozambique, there is clearly plenty of gas to supply LNG projects. In addition to the massive volumes found, the Tertiary-age reservoirs are excellent, with very good properties. The gas is dry, so little processing is needed. And the fields are only around 50 km (31 mi) offshore, so the pipeline infrastructure required is limited.

Of the gas found, around half is thought to be in one enormous structure which is in communication across the block boundary between Area 1 and Area 4. Under Mozambican law, unitization will be required. However, this is unlikely to be an obstacle to sanctioning the projects; Eni and Anadarko have been through unitization negotiations around the world before.

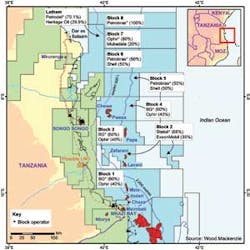

Tanzania has enjoyed considerable exploration success as well, but so far has not yielded the same scale of reserves. Wood Mackenzie estimates that around 18 tcf of recoverable gas has been found so far, with the average discovery size much smaller in Tanzania at around 2 tcf, compared to more than 7 tcf in Mozambique. The finds in Tanzania are also more spread out, so developing them will be more expensive because more infrastructure will be required.

The next 12 months are expected to see activity focused on further exploration and appraisal. In Mozambique, both Anadarko and Eni will continue with their respective appraisal campaigns before resuming exploration. Anadarko also will target a deeper Cretaceous play in the south of its block, which is thought to contain oil prospects. It is this same play that Statoil and new partner Tullow will be pursuing in mid-2013, and where Total, which farmed-in recently to the Petronas-operated areas 3 and 6, is drilling an oil prospect.

In Tanzania, BG and partner Ophir have begun an appraisal campaign focusing on block 1 in the south. Once the three-well campaign is complete, exploration is likely to begin again. In block 2, Statoil and ExxonMobil are expected to resume exploration and appraisal work in 2013. Finding additional volumes to underpin LNG trains is the aim for both partnerships.

But developing the gas discoveries will not be easy.

Both Tanzania and Mozambique are undeveloped countries with very little infrastructure or experience in developing major export projects. On the technical side, the main challenges are associated with the lack of development. There is a very limited skilled workforce able to operate oil and gas facilities in either country, so some skilled labor will have to be imported. Dedicated training programs to ensure a sustainable local workforce will be critical for future in country developments.

On the commercial side, there are a range of potential obstacles that could delay first LNG. It is yet to be tested whether there is sufficient impetus and capability within the governments and national oil companies to advance the huge legislative, bureaucratic, customs, and financial challenges that such developments bring.

Then there are the negotiations among the oil companies themselves. With some of the reserves extending across blocks and potential savings to be made from shared infrastructure, cooperation is likely to enable reserves to be monetized faster and more cheaply. However, with such a large potential prize, we expect negotiations to be tough as companies look to maximize value.

Finally, there is the question of finance: a two-train greenfield development in the region is going to cost around $25 billion. For some of the players, financing their share of this cost will be challenging and could delay development.

These challenges are not insurmountable. They have been encountered and overcome in several countries before. However, dealing with these issues is likely to push development schedules back and add to costs.

So what are the proposed schedules?

Anadarko and Eni both say they aim to bring first LNG in Mozambique on in 2018, while BG has indicated that it could have first LNG in Tanzania by the end of the decade. Clarity on whether these schedules are achievable will come over the next couple of years, as there are a number of milestones which potential exporters must achieve.

In Mozambique, both the Anadarko-led and Eni-led projects appear to be the most advanced. They have drilled more wells and discovered more gas reserves than any of the other consortia in the region. A site has been selected for the liquefaction facility, and Anadarko is about to enter front-end engineering and design (FEED) phase.

Further north in Tanzania, BG has enough gas to underpin a two-train, 5 MM metric tons/yr (5.5 MM tons/yr) project, but we believe the company is unlikely to sanction a project until it has found more gas in block 1. Indeed, BG has begun its appraisal campaign in the block, and is targeting further volumes near its largest gas discoveries. In block 2, Statoil is expected to resume drilling next year, also aiming to prove more gas.

The major outstanding milestone for Mozambique is the agreement on a commercial framework. This is in the process of being negotiated by the government of Mozambique and the Eni and Anadarko partnerships. It will determine how any LNG development or facilities will be structured for taxation and whether the joint ventures will cooperate in the construction of a single large LNG facility or pursue individual developments. One crucial advantage that the Tanzanian projects currently enjoy is that they have already negotiated commercial terms, prior to their announcement.

With so much outstanding, the present schedules are ambitious and could slip if any one of the key elements are delayed. It is also uncertain how the political picture will impact development. With presidential change and elections due in Mozambique in 2014 and Tanzania in 2015, failure to establish political consensus on gas exports also could impede progress.

Can East Africa LNG secure a market?

Ultimately, how much of East Africa's resources are monetized and how quickly that happens will depend on how it competes with other potential suppliers in the global market place. From 2017 onwards, we forecast that at an average of 20 to 25 MM metric tons/yr (22 to 27.5 MM tons/yr) of new supply will be required every year to meet global LNG demand.

With its potential access to both Atlantic and Pacific markets, and its location close to the fast-growing Indian market, East Africa is well positioned to meet much of this potential demand. Buyers are keen to see another potential source of supply developed in order to ensure continued diversification of the supply mix.

However, there are several other potential LNG exporters emerging and these will compete for market share in the premium Pacific market, possibly driving long-term prices down. How much of this market is secured by East African LNG will be determined by the projects' ability to differentiate themselves from other suppliers, with economics and security of supply likely to be key factors.

The author is head of Sub-Sahara Upstream Research at Wood Mackenzie.