Allseas has committed to its second new construction vessel within the past 12 months. But the €1.3 billion ($1.7 billion)Pieter Schelte will take the pipelay specialist into new territory, also providing heavy-lift and platform removal capability.

The first contract for the giant newbuild vessel - the 86 MW power package, including thrusters and dynamic positioning system, was awarded late last month. More long-lead equipment orders will follow over the next few months. As for the hull, the company is currently evaluating and negotiating with yards in the Far East, with a view to starting construction next spring. If the schedule goes to plan, the vessel should be ready for service at the end of 2010.

In pipelay mode, thePieter Schelte will be pitched mainly at large diameter installations, but its tensioning capacity of 1,361 metric tons (1,500 tons) will far outstrip the existing global fleet, including Allseas’ own flagship vessel Solitaire. For field abandonment operations, it will be equipped to handle topsides lifts of up to 48,000 metric tons (52,911 tons) and jacket lifts up to 25,000 metric tons (27,558 tons) - well in line with coming requirements for North Sea decommissioning.

Allseas began conceptual studies for a heavy-lift/abandonment vessel in the mid-1980s, when the North Sea’s decline seemed some way off. Its original plan involved joining together the hulls of two existing tankers, creating a 300-m-long (984 ft) catamaran. A U-shaped slot at the bow would allow the vessel to position itself around a platform jacket, before starting the extraction process.

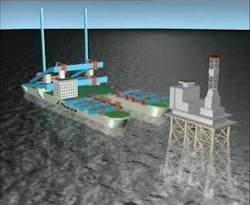

More recent computer generated image of thePieter Schelte in abandonment mode.

According to chief executive Edward Heerema, “Joining two existing vessels was a good plan at the time because the VLCC types we wanted were abundantly available at a low price. That situation changed through the 1990s as the old carriers built from mild steel with heavy wall thickness were gradually taken out of service. Their replacements, constructed with higher strength, thinner walled steel, were less suited to our purposes.”

By the end of the decade, however, the North Sea’s future was causing widespread jitters, with operating costs rendering some older installations a liability. This encouraged Allseas to establish a new company, Excalibur Engineering, to commercialize its concept. It also revised its long-held stance favoring conversions.

“Given that the newer VLCCs were less technically suitable, and expensive,” Heerema explains, “a newbuilding started to look a better option for our cash. And a newbuild could be engineered to take the strain of lifting a jacket over the stern ofPieterSchelte, making it more versatile than our previous plan of taking the jacket sideways on.

“Also, our mooring concept had changed by that point from anchoring to dynamic positioning. In the 1980s, the industry’s mindset was fixed on water depths of up to 180 m (591 ft). At those depths you could anchor a vessel easily, but things changed as operations headed into deeper water. Switching to DP was clearly the way forward, but building that into a VLCC also gives you penalties in terms of the complex outfitting work you have to do.”

ThePieter Schelte evolved in other ways as time went on. “One advantage of spending so much time on this project,” Heerema says, “is that you continue to invent better lifting solutions. As you study different North Sea platforms, you discover that your solution has potential clashes with existing structures. One platform’s layout may be very well suited to your idea, but being sufficiently ‘all-round’ is harder to achieve.

“We kept running into problems, both for topsides lifts and jacket lifts, causing us to throw out our previous notions. That process of re-thinking dozens of times, in the search for greater versatility, can almost drive you to despair. But around six years ago, we found our present topsides lift system, which should allow us to deal with any design of platform. “That has had a very significant effect in bringing this project forward. In the past years, the overall concept has changed less and less.

Over time, the vessel’s length has been extended, providing the deck space needed to accommodate very large jackets. The company also found that the behavior of the ship improved with a larger hull, affording greater stability in bad weather.

“The ship is so large that in operating wave heights of, say, 3 m (10 ft) significant, the vessel’s movements are smaller than those of a semisubmersible. Nevertheless, a motion elimination system was incorporated on the topsides lift method from the start. We also found that the longer length gave the vessel better streamlining for through-water flow while in transit.”

The finalized dimensions include an overall length of 360 m (1,181 ft), a breadth of 118 m (387 ft) and a variable draft. The U-shaped slot has been retained - 122 m (400 ft) long and 52 m (171 ft) wide - but the strengthened center line section will limit transit speed to a maximum of 11 knots. So this can no longer be classified as a catamaran.

Either side (lengthwise) of the slot are eight lifting beams, together capable of supporting topsides weighing up to 48,000 metric tons (52,911 tons). “The hydraulics are very important,” Heerema stresses. “Any ship, even the size of thePieterSchelte, will move in any wave. So when you prepare to lift the topsides clear of the platform, your lifting system must be stationary relative to the jacket while fastening the load. Then when you have applied the clamps, lift-off has to be swift, as any re-impact must be avoided. Given the large mass of the platform topsides involved, anything in contact would be destroyed. Our analysis has shown, therefore, that a motion elimination system is essential.”

At the vessel’s stern, two portal cranes will be able to lift jackets of up to 25,000 metric tons (27,558 tons) by means of a tilting beam system. This allows tilting of the jacket from its vertical (lifted) position to a horizontal position on the vessel’s deck.

Allseas intends to build its own transportation barge in parallel with the hull construction program. “That’s because the big barges suitable for the really heavy loads are all owned by our competitors. We will construct our barge to fit exactly intoPieterSchelte’s U-shaped slot. Smaller loads, however, can be dealt with by smaller rental barges,” Heerema says.

Investment timing

North Sea operators have provided input indirectly into the concept, Heerema explains. “Over the years, various oil companies asked us to do studies of their platforms for installation as well as removal. If you work out the peculiarities of each platform, you can identify problems the lifting system might encounter. In a way, these companies have helped us by giving us their problems; however, all the ideas and solutions have been developed by us in-house.

The decision to invest required two essential steps. “First, we needed to see a definite market emerging for the removal of large platforms. That process has been deferred and then further deferred over the past 20 years, but now the deferral period appears to be much shorter, so the market for this vessel is no longer moving away,” Heerema says.

Finance was the other factor. Following resolution in 2006 of a nine-year legal dispute with Sembawang, Allseas suddenly had funds available for a speculative newbuild. The €350 million ($467 million) settlement arose from the original conversion ofSolitaire in 1995. Problems in Singapore led to the work eventually being transferred to Swan Hunter in the UK. “With hindsight,” Heerema says, “maybe we could have built PieterSchelte instead of Solitaire, but at the time, it was more sensible to invest in a pipelayer than a lift-ship.

Solitaire had been a big cash drain, due to the problems associated with switching yards, Heerema says. “But this settlement helped, and we also have a healthy cash flow because of the current shape of the market. That allowed us to enter into a significant bank loan for this project.”

Over the past five years, other installation contractors and vessel designers have pushed their own decommissioning concepts, but most have fallen by the wayside. Heerema believes those that remain are more limited technically.

PieterSchelte will be able to install heavy-walled pipes with an outside diameter of up to 1,524 mm (60-in.) Its 170-m (558-ft) long stinger - 30 m (98 ft) longer than Solitaire’s - will send pipes into deepwater at a near-vertical angle. And the seven welding stations spaced out along the deck - two more than on Solitaire - should lead to higher productivity.

The 86 MW power plant is roughly double the size ofSolitaire’s, which is already the biggest in the world for a pipelay vessel, he claims. “So this is a major leap. PieterSchelte’s 12 thrusters are larger than Solitaire’s, but they are not an extreme step-change in size. The same applies to the diesel engines - our vessel has eight, compared with a normal four.”

Allseas intends to offer the new vessel for projects worldwide, including heavy lifts for field development. “We could pick up topsides from yards in the Far East and take them to another part of the world. Our installation technique is exactly the reverse of the removal procedure.” However, he concedes that there is no sign at present of under-capacity in the heavy-lift sector.

For heavy lifts or platform removals, larger loads (>10,000 metric tons [11,023 tons]) would offer better profit margins. But the vessel will be available for lesser jobs. “If we have an idle slot, we would rather do a smaller lift to make a bit of cash flow than have the vessel lying idle in port.”

As for fitting and removing equipment spreads to fit the various assignments, “It’s mandatory to do this very quickly,” Heerema says. “Our aim will be to turn things around within days; otherwise’ the process becomes too expensive in terms of vessel time.”

PieterSchelte is the latest in a series of improvements and expansions to Allseas’ fleet in recent years. Aside from Solitaire and Audacia, the company also has added a shallow-water barge, a trenching support vessel, and a survey vessel.

Audacia is still under construction, but behind schedule. “There have been considerable delays,” Heerema says, “due to the enormous shortage of welders, cable pullers, and so on. Our subcontractors are also struggling to get enough people. But we still expect to have the vessel ready for its first job in the North Sea this summer, following sea trials off Rotterdam.”

As for pipelay dayrates, Heerema says, “It looks like the good years we’ve had lately will last a bit longer, but I am more optimistic only for the short term. So much capacity has been added to this market - we’re guilty of this too. And seeing all the other vessels being fitted out or about to be fitted out, I foresee pipelay prices dropping back again.”