Liftboats, once limited to the confines of the Gulf of Mexico (GOM), have gone global. Liftboat service companies report a major increase in business driven by international customers from as far away as China and Nigeria.

"(We have seen) a ten-fold increase interest in liftboats by the international marketplace during the last three years," said Mike Audirsch, Manager of International Business Development for Cudd Pressure Control.

Other fleet operators; including Danos & Curole, Superior, and Global, report similar levels of interest. About half of the inquiries come from multi-national oil companies. The remainder are from independents and state oil companies. According to reports, talks are underway with operators in China, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico, and West African countries, including Nigeria.

The primary driver behind this interest is the development of a new, larger class of liftboats that are better suited for international operations, though that was not the original plan. In part, these Class 200 and 250 (class numbers refer to leg lengths) boats were built in res-ponse to deeper-water activities in the GOM.

Deepwater liftboats

Historically, the liftboat market was a cottage industry of sorts, operating under its own traditions and immune to oversight. In 1991, the United States Coast Guard (USCG) began inspecting some of the newer boats, while grandfathering in the older vessels. The USCG recognized it had come on the scene late in the game and did not want to disrupt the market by imposing new regulations on existing vessels.

Then came 46 CFR Subchapter L. The new regulations, applying to boats constructed after March 15, 1996, reflected the USCG's inability to develop a workable definition for these hybrid craft. Because liftboats float, Subchapter L treats them as Offshore Service Vessels (OSV)s. Because liftboats elevate, the regulations class them with Mobile Offshore Drilling Units (MODU)s.

The effects of these new regulations were devastating to the market, driving up costs. For example, Conrad Industries delivered a Class 175 boat in 1997 for $4.2 million. The sister ship delivered a year later cost $6.4 million and suffered a 40% reduction in variable load capacity. Under the old regulations, Semco's proposed Class 250 boat had a price tag of between $8 and $10 million. When Subchapter L came into effect, the price of the vessel increased by $4 million.

Due to these regulations, no newly constructed liftboat could compete with an equivalent pre-Subchapter L boat. Consequently, older boats, obsolete by every standard except regulatory, have escalated in value ensuring they will remain in service indefinitely. Of the 204 liftboats active in US waters, 184 are pre-Subchapter L.

To compete, owners who want to invest in new construction of liftboats for the GOM market must build for deeper waters, where day rates are higher and few grandfathered boats can venture. Of the 26 American-flag boats, Class 200 and larger, built or under construction, only six are grandfathered.

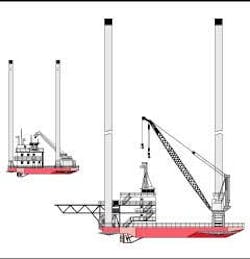

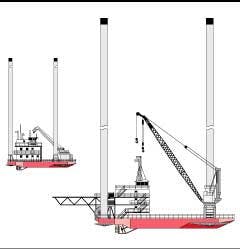

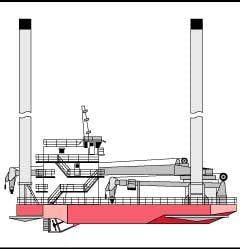

The Semco-built Dixie Endeavor, a sistership to Superior's recently delivered Dixie Legacy, is shown in comparison to a typical Class 150 lift-boat. The Dixie Endeavor will be ABS classed with 250-ft legs rated for 190ft of water with twin SeaTrax 175T cranes, a helideck, and 66 berths. Propulsion and maneuverabilty is assured with four stainless steel, five-blade propellers and a 450hp bow thruster.

Semco's Dixie Endeavor, scheduled for commission next year, is typical of the new breed. This large boat (156-ft 6-in. in length, and 103 ft in beam) will be able to operate at 180 ft. water depth. It carries two 175-ton cranes, mounted concentrically on the forward legs, and has a variable deck load capacity of 750,000 lbs. A bow thruster supplements the four-prop propulsion system.

Two recently delivered GOM liftboats -- the Superior Champion and the Danos & Curole Ana jointly hold the water depth record at 190 ft and the variable load record at 2 million lbs.

Boats of this size, complexity, and capitalization have changed the way South Louisiana fabrication yards work. Design, once the province of the yard foreman, is now in the hands of naval architects, structural engineers, and propulsion specialists. In addition to meeting USCG requirements, some of which are more demanding than required for overseas operations, these new domestic vessels receive approval from ABS or other recognized classification societies. In addition, boat owners and fabricators increasingly take advantage of the professional competence of design staffs to break with traditional concepts. In other words, Louisiana liftboats have become world-class products.

Industry initiatives

For years, industry has worked hard to spread the word about the virtues of these hybrid craft, created by marrying a crane/deck barge hull with a MODU jacking system and workboat propulsion. Self-propulsion, combined with large, lightly loaded spud cans and high-speed jacking gear means that liftboats deploy quickly. Because they typically work in familiar locations, only cursory site surveys are needed. The barge hull provides maximum deck load. Cargo can be skidded on and off by raising the deck to platform level, or moved by the crane, which is standard equipment on all liftboats. Because the hull can be elevated, lifting operations are not affected by weather that would defeat a conventional crane barge.

Danos & Curole (D&C) was one of the first fleet owners to seriously pursue overseas business. In 1992 the company opened an office in Lagos, Nigeria. Four years later, operations expanded into Venezuela. D&C currently has four boats working in Nigeria and one in Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela.

Last year, Global deployed two boats to the Bay of Campeche offshore Mexico, to serve as accommodations platforms for Pemex. It is worth noting that the boats made the voyage from their Louisiana homeport entirely under their own power.

At latest count, 43 liftboats are active overseas, including 17 boats off West Africa, 12 in the Arabian Gulf and one, operated by Halliburton, in the UK Sector of the North Sea.

The Halliburton boat in the North Sea, the Irish Sea Pioneer, was the first liftboat to be purpose-built for overseas operation. Commissioned in 1994, it sails under the Panamanian flag. Sedco followed up with three sister vessels, the Prisa 110, 111, and 112, fitted with cantilevered drilling packages for work in Lake Maracaibo.

International market requirements

Boat owners contemplating going overseas must conform both to flag-state requirements and local regulations, which vary with the country and area. Some jurisdictions require SOLAS certification. Only a handful of recently constructed boats carry this certification, although several are described by their owners as International Convention for Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS)-ready, which means additional fireproofing has been installed in quarters and space left for lifeboat davits.

Ex-pat owners will be confronted with cultural differences, language barriers, and infrastructures that, at best, never come up to GOM standards. It helps to put an advance party on the ground for a year or more prior to the anticipated move. Even so, "It's a heck of a learning curve," said Randy Reed, GM of the Special Services Division for Global Industries LLC, "but if you're going overseas, you have to step into that room."

Under construction at Conrad's yard in Morgan City, the Kaitlyn Eymard was designed by Dynamics Marine. It will be a Class 200 Subchapter L Liftboat rated for 160-ft water depth with a TechCrane 125T, an EBi 37T crane, and 42 berths.

While Class 120 boats successfully operate in Lake Maracaibo and in the Niger Delta, most operators require large, heavy-duty Class 200 and 250 vessels to meet variable-load and deck-space requirements. Water depth capability is a secondary consideration.

Variable load and open deck space are more critical than in the GOM, where liftboats often operate in a spot market. Boats work from dockside and carry no more equipment than needed for the job at hand. The time-duration contracts used overseas give operators complete control over work scheduling. Boats are expected to perform a variety of tasks between visits to dockside for resupply. All the necessary equipment must be aboard.

In addition, foreign operators, conditioned by their experience with jackups, expect liftboats to carry a lot of people in addition to the crew (PAC)s for construction support. Some oper-ators have asked for 60 berths in addition to crew spaces. Boats working in developing countries need extra accommodations for locally hired crewmembers. Day rooms or other recreational facilities also can be required.

Operational difficulties depend upon the area. For example, severe tides off some parts of India leave submersible pumps high and dry. Earthquake-induced waves present a hazard off China. And nowhere are bottom conditions known with the certitude of the Gulf of Mexico. Locals can sometimes provide useful information, but boat crews must be able to evaluate seabed conditions that range from soft muck in Lake Maracaibo to hard rock off Brazil. It may be necessary for vessels to be equipped with soil density, jacking-load, and leg-stress monitors in addition to the contemplated side-scan sonar.

Next generation liftboats

Shell and Global Marine have recognized the emergence of a world market as an opportunity to reevaluate aspects of liftboat design that have been standard practice for two generations. Shell's recent request for quotations (RFQ) invites bids for the design and construction of a Class 250 boat to be used in the UK and Danish Sectors of the North Sea. The vessel will be configured to handle all well completion operations, thus relieving MODUs of everything except drilling. The boat also will carry and support a remotely operated vehicle for pipeline survey.

One of the unspoken rules of liftboat design has been that job requirements should never intrude below decks. If, for example, a client requests a fuel delivery, the fuel is carried on deck. Shell breaks this rule by specifying that fuel, potable water, and lube oil hull tanks should have the capacity for two weeks' operation, plus 50% excess for off-loading to platforms.

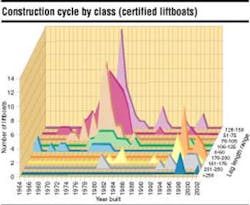

This graph shows the majority of the certified liftboat fleet with legs of 150-ft and less were built in the mid-1970s to late 1980s. Liftboats with more than 150-ft legs have, for the most part, been built since the mid 1990s.

Global's RFQ invites bids for the design of a Class 250 boat that, while built to Subchapter L constraints, will be capable of rapid conversion to international standards. Global suggests that a hull length of about 170-ft and an 8-ft beam would be appropriate. The barge hull will, unlike traditional liftboats, have its hard edges softened by shipshape lines.

A unique feature of the Global boat is its propulsion system: it will employ steerable thrusters, two on the stern and a dropdown, tunnel-mounted thruster on the bow. All other liftboats drive through one or more propellers, each coupled by a shaft to a prime mover. A few of the larger boats have bow thrusters as an aide to maneuverability, but not for main propulsion.

Steerable thrusters with variable pitch and rpm control give unmatched maneuverability. These vessels work close to platforms and sometimes need precise station-keeping.

Thrusters eliminate all prop shafting and at least one prime mover a vessel this size would require. Engine-generator sets can be located amidships, near the center of buoyancy. Conventional liftboats are designed around the constraints imposed by their propulsion systems. That is, the mass of the prime movers must be concentrated aft so that short, and relatively vibration-free, prop shafts can be used. This gives unladen boats a stern-down attitude that wastes fuel and costs freeboard.

The Shell and Global boats represent early steps in the process of internationalization. More innovations will come as liftboats acclimate themselves to a variety of worldwide environments. The caisson leg will reach its design limits in water depths more than 200 ft. Hydraulic jacking systems may not prove compatible with North Sea winters. Rather than a "world boat" evolved from the GOM model, the market may see area-specific designs, reflecting local environmental, regulatory, and economic realities.

Authors

Paul Dempsey is a freelance technical writer with more than 20 years experience in the offshore industry, including eight years as an oil-industry magazine editor and reporter. He has also written over 30 technical books.

Larilla Templeton is the principal for Templeton & Associates, a naval architecture firm active in the liftboat industry. Her experience includes work as a design engineer for a major offshore rig fabricator and Marine Superintendent with an international drilling contractor.